What is intelligence?

Intelligence is not IQ. It is IQ plus something else plus something else.

In my last post I tried to pinpoint the nature of intellectual creativity. Today my ambitions are much higher: I'm aiming at defining intelligence.

I know, this is supposed to be very difficult:

"Intelligence is like pornography. I can't define it, but I know it when I see it", science fiction writer Jack McDewitt said.

But the thing is, I think I can define pornography. How about this: Pornography is any visual, auditive or text-based material which primary purpose is to incite sexual excitement in its audience. If the purpose is artistic or scientific, it is not pornography, however naked it is. If the purpose is political, it is also not pornography. This explains the failure of "feminist pornography". As soon as the highest purpose is no longer plain sexual excitement, the material produced incites much less sexual excitement. Pornography simply is material with no higher purpose than the sexual excitement of the viewer. (I must admit that this definition contradicts how I used the word pornography in my recent post on pornography, because I called romance literature pornography although the purpose of romance literature is more general emotional excitement than pure sexual excitement. I use the tradition to also use the word pornography in a wider sense as an excuse to my previous stretch of the word.)

That being said, let's turn to intelligence. I think the word intelligence in its everyday use can be defined as the ability to learn and observe and to come up with new and useful ideas. That is, an intelligent person is a person with a high capacity for both learning and useful thinking. A person who learns a lot but can't apply that knowledge in any useful way is not considered intelligent - only studious. A person who randomly spits out incomprehensible, useless ideas is not considered intelligent - only slightly mad.

IQ + creativity + selectivity

Last time I drew mind maps for two types of high IQ people: The kind with potential to make new, ground-breaking discoveries and the kind lacking such potential. I claimed intellectual creativity consists of the ability - or compulsion - to make new connections between concepts and to see new patterns.

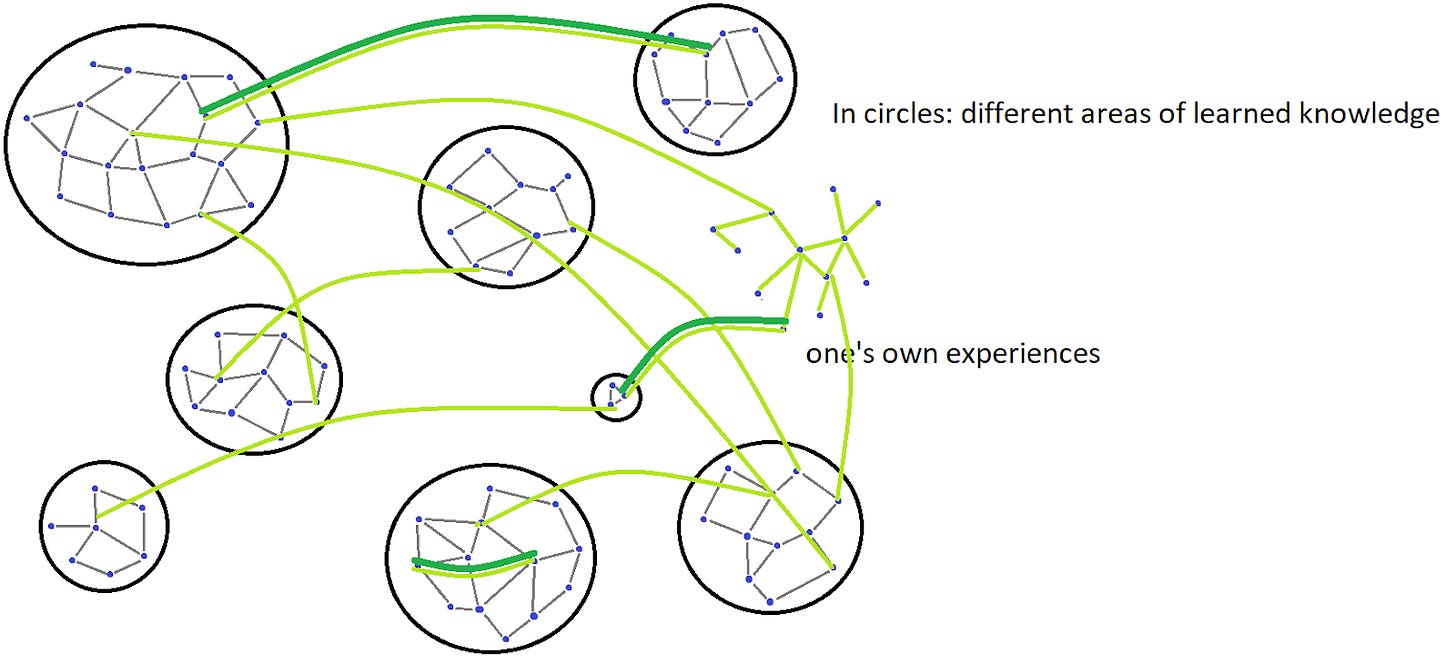

However, those maps were highly simplified. The map of the potential genius is identical to the map of a lunatic. What separates the genius from the lunatic is a rigorous sorting process of thoughts. In the lunatic, that sorting process doesn't work. Crazy people - schizophrenics in particular, but crazy and half-crazy people in general, have a bad sense of telling their relevant connections from their irrelevant connections. I think a more detailed map of a sane, intelligent person could look like this:

The light green lines are spontaneous connections between concepts. The striped lines of light green and dark green are connections between concepts that are tried, tested and deliberately thought over. Intelligent people do not only possess the ability to create new connections between concepts. They also know how to select between those connections. They spend a lot of effort to find out which are good, which are bad, which do only sound funny?

And the winner is…

I have now outlined three components of intelligence:

Total information handling capacity (roughly what is measured by an IQ test)

Intellectual creativity

Sorting ability

All three are required for novel thinking. But I think the last one is the most crucial one. People who are only good at information processing often fail to create new thoughts. Intellectually creative people often create ideas that are good for nothing. Only being a good learner and a creative thinker is not enough. What distinguishes highly intelligent people from high-IQ crackpots is the formers' ability to sort through the ideas they produce.

No single person can acquire all human knowledge in the world. Not even those with the highest IQs. Everybody has to choose. I think the core feature that distinguishes really intelligent people from mere good learners and eccentrics is mastery of intellectual choices. Which thought to follow and which thought to drop? Which book to read and which book to ignore? Which tracks are promising and which tracks just lead to the same old stuff? Highly intelligent people have an intuition that leads them to relevant knowledge to a higher degree than less intelligent people.

An IQ 123 genius

Edward O. Wilson was one of the most prominent evolutionary biologists of the 20th century. In 1975 he wrote the book Sociobiology: The New Synthesis, in which he outlined principles for what would become evolutionary psychology. Wilson saw what only few people saw at the time, but many more would see decades later. Isn't that the common definition of a genius? Someone who sees what few others see at the time, but that many others come see at a later time.

And still, Wilson himself claimed to have had his IQ measured to 123. He was not great at math and learned calculus at the age of 32, when he already was a tenured professor at Harvard University. Also Charles Darwin admitted to such intellectual limitations, Wilson writes in his 2014 book Letters to a Young Scientist.1

Would Wilson have been an even better scientist with a higher IQ? I doubt it. Wilson could study the world, make up hypotheses, sort among his hypotheses, construct experiments and make highly informed general conclusions. He didn't have the disposition to become a physicist. But the vast majority of physicists don't have the ability to become ground-breaking thinkers in biology either.

In Letters to a Young Scientist, Wilson tells about an experiment he invented. When studying ants, he noticed that they tidy away dead companions and put them in a "cemetery" outside the compound. But they only do so after a day or so. Wilson guessed that it was their sense of smell that detected decomposing ants. He also guessed that since small brains have limited capacity, they would only react on one chemical of decomposition. So he tried different artificial chemicals that make up the smell of decomposition and sprayed them on an ant dummy. It turned out that the ants only carried away dummies that were sprayed with oleic acid and one type of oleate. Other chemicals were either ignored or caused alarm.2

I think the ability to carry out such simple experiments is a sign of high intelligence. People who somehow know to pose the relevant questions at the right time are the most intelligent people.

Very high IQ people tend to have an extraordinary capacity to absorb information. That doesn't help very much, if they are also not unusually good at selecting which information to absorb. If they don't pose the right questions, they will not get any interesting answers. Then it doesn't matter how much information they can absorb during a given time. They will just get random information, or information suggested by people around them.

In theory, a person who is both great at posing the right questions and reading all information that could answer those questions should be at an advantage compared to those who only pose the right questions. In practice, I'm not so sure that principle is very much applicable above a certain level of information processing capability. I can take myself as an example. I wouldn't be sad if I could suddenly read twice as fast or if every statistical formula and expression suddenly appeared crystal clear to me. I have the impression that many people can read more text than me during any given time and are more at ease with numbers, and I wouldn't mind having their abilities. When I sometimes write information-heavy articles with many sources, I'm feeling that it wouldn't exactly hurt to have a better memory for where-did-I-read-which-fact.

Still, I remember enough of where I read things to actually write the texts I want to write. Limits to my information handling capacity are a nuisance, but they don't decide what I write and don't write. At the end of the day, it is not my limited ability to read or deal with numbers that is the main obstacle for my attempts to think. The very big number one obstacle is the limits to my imagination. When I find a book I assume is filled with useful, interesting information I seldom find it too difficult to read. Reading it twice as efficiently would have been nice, but actually not important. Finding the relevant books is the tricky thing, not reading them. For that reason, I wouldn't trade the smallest crumb of the imagination I have for more information processing capacity.

Don't let IQ bring us down

I can sense that the long tradition of IQ testing has pushed the word "intelligence" from its original, everyday meaning to the more narrow definition the thing that correlates with results on an IQ test. I think that slide of significance should be resisted, if possible. Speaking and thinking clearly get much easier if there are clear concepts to use.

Imagine that a test of physical beauty was developed. With today's technology of artificial intelligence, it would be entirely possible to ask people who they consider beautiful, measure the people who were rated and create a machine which anyone could enter in order to get their beauty quotient. Such a machine would definitely be useful for fashion brands on the look-out for models of certain proportions. But for most of us, it would have been very sad if the word "beauty" came to mean "beauty quotient".

I think human intelligence has several similarities with human beauty: It is partially subjective, it is elusive and always somewhat flawed. No one is perfectly beautiful, but many people are beautiful. No one is perfectly intelligent, but many people are intelligent. Some people see beauty where others don't see beauty. Some people see intelligence where others don't see intelligence. I'm sure both beauty and intelligence can be measured to a certain extent. And I think the measurement attempts, also if rather successful, should not be allowed to replace the original concept.

A match for the artificial

One reason to keep the concepts as clear as possible is the importance of distinguishing the uniquely human aspect of intelligence from machine learning. If we mix up the concepts intelligence and IQ, we risk getting unnecessarily nervous over machines. The component of intelligence that is most of all being measured by IQ tests is information processing ability. Computers are getting better at that all the time, while humans are standing still. In some areas of information processing, computers surpassed humans many decades ago: Give a computer a memory test for humans, and it would get astronomic scores. More progress like this is to come.

However, the two other components of intelligence are specific to humans. Computers just don't possess intellectual creativity. They are great at statistics, but they don't possess that mysterious ability to make associations between concepts out of nowhere. They also don't have the sense to select the relevant from the irrelevant. They can collect data on what most people think is relevant, but that's it. An AI can handle more data than any human. But it doesn't have a better sense of relevance than the average human who produced the data. What the average human finds relevant, the AI finds relevant too. The superior sense of selecting relevant knowledge that some humans possess is not built into it.

We have no idea why humans have the capacity of novel thinking and of sorting the relevant new thoughts from the less relevant new thoughts. We don't know much about how our own brains work at all. I have discussed this with rationalists who fear AI development and they say, more or less, that since we don't know how our own intelligence works, it might turn out to be built on very simple statistical operations, just like a computer. And if our intelligence is built on very simple statistical operations, then we can happen to build an intelligence in our likeness without realizing how easy it is.

In the AI risk debate, I think far too little is being said about the human side of the potential disaster. There is a lot of talking about how computers could become "intelligent" and comparatively little talking about what human intelligence actually is. I'm in no way sure that artificial intelligence will never achieve this-or-that. But I think that investigating human intelligence can make the other side of the equation clearer: What can humans do that computers are not very good at?

I think for such reasons, we should carefully investigate the nature of human intelligence. We shouldn't just make quick assumptions about how we do it when we think. Instead we should both study psychology and make all observations we can through introspection. Then we will know more about what assets we have to resist the artificial.

Edward O. Wilson, Letters To A Young Scientist, 2014, end of chapter 2

Edward O. Wilson, Letters To A Young Scientist, 2014, chapter 4

I'm fairly certain that the purpose of writing or commenting on blog posts is to excite sexual arousal in potential readers just like half of everything else we do.