Confessions of an everyday apopheniac

IQ measures ability to use concepts others have developed. The ability to think new things is something else entirely

In my first post for this blog, I claimed IQ and thinking ability are two different things. They tend to correlate up to a point, just as people's ability to run and jump correlates up to a point. After that point, the ability to recognize patterns and the ability to think become different sports.

One thing I didn't even try to explain: What is thinking ability, really? I had a long and interesting discussion about that with Apple Pie, who writes Things to Read. He taught me a new word: Apophenia. At first sight, Apophenia doesn't look like a promising concept for describing thinking, since it only describes faulty thinking. Apophenia means seeing connections and patterns where there really are no connections and no patterns. That is, the opposite of successful thinking, which is finding new and meaningful connections and patterns.

Confessions of an apopheniac

Still, the apophenia concept immediately struck a nerve with me, for one simple reason: I'm a self-recognized apopheniac. My mind is constantly making connections and seeing patterns. And those connections are most often meaningless, trivial or outrightly wrong. Only a few of the connections I make are worthy of further examination. And out of those, only a tiny percent go further and become blog posts (the highest goal!)

For me it is self-evident that my good ideas and my ubiquitous less good ideas share the same origin. Both good thoughts and meaningless thoughts are fundamentally thoughts. The difference between me and your average conspiracy theorist is only that I (hopefully!) know how to discard my less good ideas before I start taking them too seriously.

Before I gained that level of intellectual ability, I was a full-blown apopheniac. I clearly remember one instance of clear-cut childhood apophenia: Until I was four years old, my older sister and I shared a room. In that room we had a note board. On that note board were two identical postcards with harbor seals. One of the cards was attached to the board with two stick pins. It hung perfectly straight and orderly. I knew that was my sister's card. My card was attached to the board with only one stick pin. It was visibly tilted.

I had a strong feeling that the way the cards hung on the wall must mean something important. I wasn't intellectually advanced enough to figure out that most likely, a parent with many other things to do had run out of stick pins or didn't just think much about how to attach two cards to a note board. It wasn't even obvious to me that my parents had attached the cards, because as far as I could remember the cards had always been there.

Luckily, I didn't grow up into a conspiracy theorist believing in hidden messages coded in straight and tilted postcards. Instead I slowly learned to sort among my perceptions of connection, pattern and meaning. With time, I learned to dismiss the most intellectually implausible connections my mind suggested to me.

Still, I have never doubted that meaningful thoughts and meaningless thoughts are created by the same mental processes. The cost of once-in-a-while having a useful new thought is to have many rather useless thoughts in between. A moving intellect moves in all directions. Concepts constantly jump, and they do not always land well.

Why doesn't everyone agree about this?

For that reason I'm a bit surprised at the persistent distinction between flawed thinking and proper thinking. OK, psychology inherently is about seeing the difference between the normal and the pathological. But still. Don't most people who think independently perceive all the noise their minds produce?

Maybe I'm doing more introspection than most people, because almost every day I work with manual tasks without listening to music. That seems rather unusual: Most workers I know listen to the radio all day long. For that reason I probably spend more time with my imperfect thoughts than most people. Most people either voice over their thoughts with sounds, or have their thoughts disciplined in a certain direction by an employer or a school. The opportunity to let thoughts roam free might be a rather rare privilege.

Still, I think the gray areas between the delusional and the ingenious are obvious for everyone who looks for them. Humor is one example. Making a joke means making a connection between concepts that is deliberately false, but still somehow meaningful. It can be an exaggeration - humor often is an exaggeration that makes an existing principle appear in a clearer light. It can also be an exposition of the arbitrariness of language, in the shape of word games. Whatever it is, it is right there in the gray zone between the meaningful and the meaningless - not meaningful in itself, but making the meaningful more meaningful.

Looking at the history of science, philosophy and, especially, the creative arts, I'm definitely not the first person in history with a mixture of good and plain bad ideas. In the 17th century, Isaac Newton saw what others didn't see in a falling apple (yes, that legend appears to be true, according to Wikipedia). He also saw what others didn't see in the importance of alchemy. In 1982, chemist Kary Mullis got the idea that led to the Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) method for multiplication of DNA sequences, an invention that earned him a Nobel Prize. Subsequently, he got ideas that he was abducted by aliens, that the HIV virus is not the cause of AIDS and that astrology is as scientific as any other discipline. Mullis used his great talent as a chemist to make LSD and has credited the drug for his conception of the PCR method.12

Apophany and epiphany, where is the neutral term?

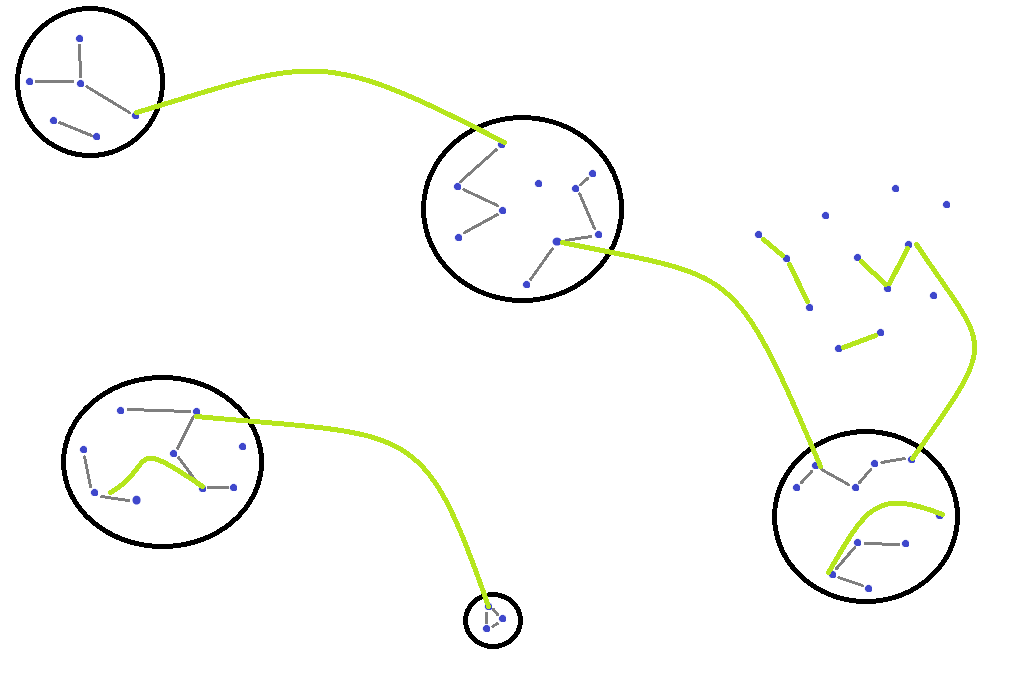

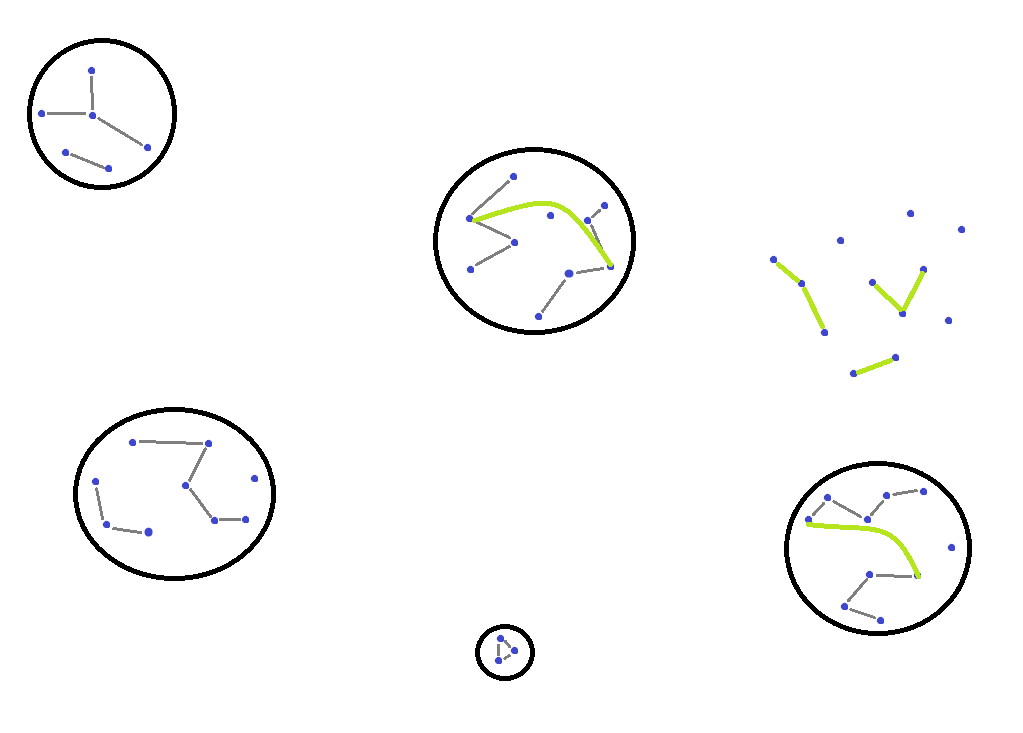

I'm convinced that the price for having occasional epiphanies is a steady stream of apophanies. And I think different people have very different frequency of original thoughts, good as well as bad. Many people don't seem to think much about important stuff. They just learn and then perform the intellectual operations they have learned. Through following the instructions, they avoid being overwhelmed by meaningless, annoying connections between concepts. But they also seldom come up with new and useful thoughts.

The presence or lack of this kind of creative thinking seems to have little connection with IQ. There are very high IQ people who are low in intellectual creativity. More than most people, they will do things right. They will be productive workers, they will be conscientious parents. But they will definitely not be geniuses.

I have previously argued that IQ becomes an increasingly meaningless measure the higher it becomes. I'm not so sure anymore. I'm still convinced that high IQ is not a measure of ingenuity: There are too many high IQ people who are definitely not geniuses, as I wrote about in my first anti-IQ article. But when I look at my short list of now-living high-IQ freaks again, they seem to have one thing in common: They are all extremely good learners. They don't think better than anybody else. But they learn a lot and early in life. While I read around a bit about very high IQ people in general, I thought it seemed plausible. Those people don't show an unusual ability to develop new, useful ideas. But they seem indeed to be exceptionally effective students.

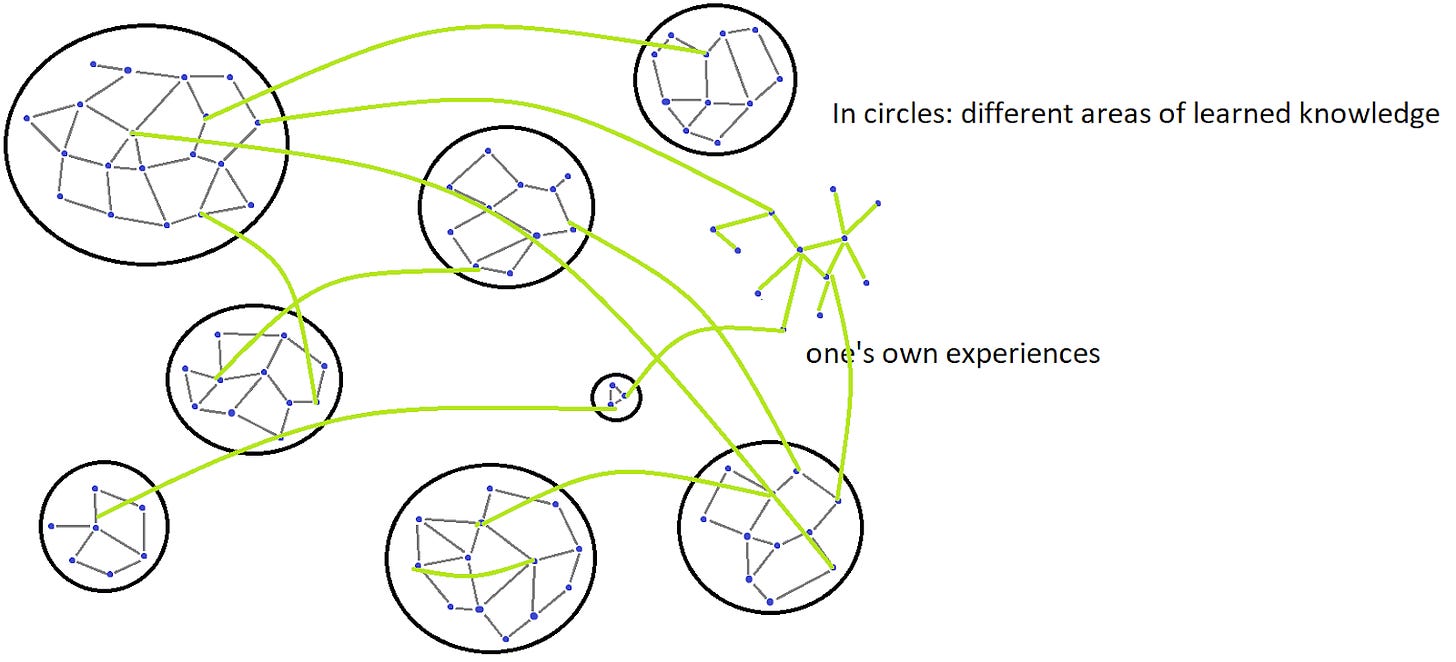

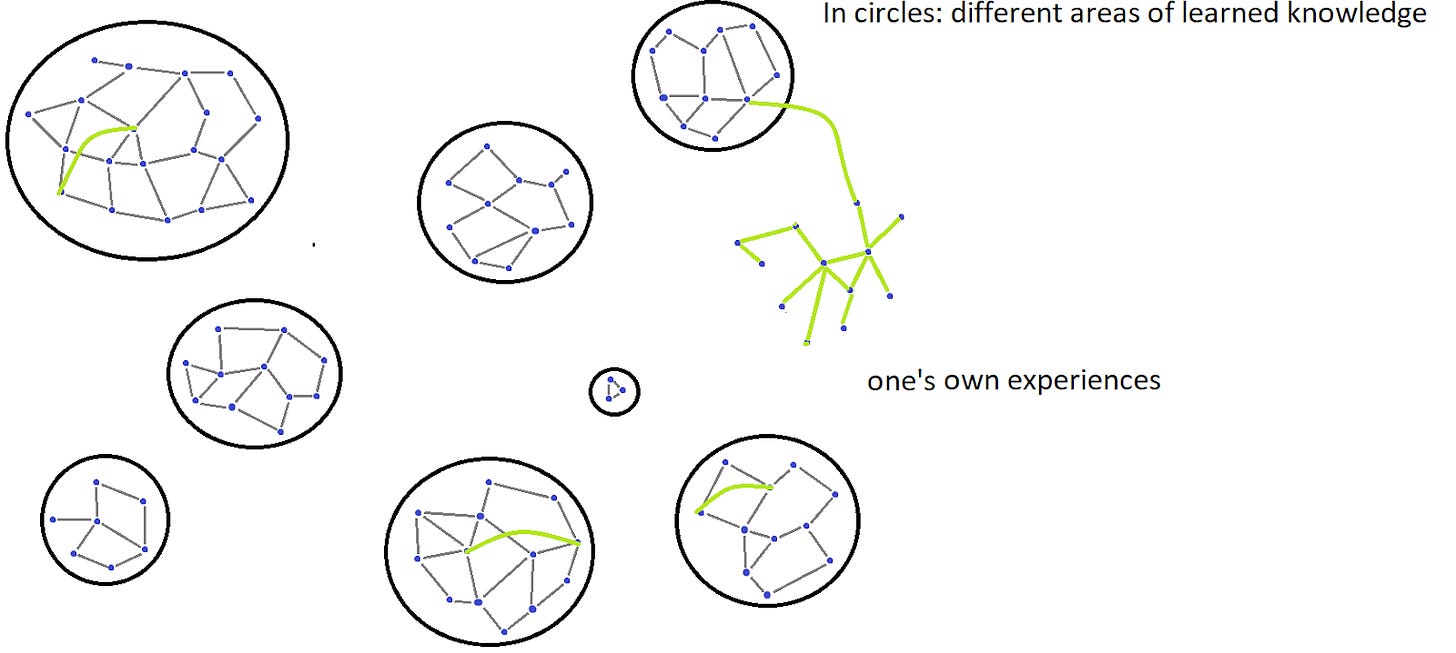

For that reason, I guess IQ most of all is a measure of information handling capacity. High IQ people can learn many concepts and how to use them properly. Low IQ people can learn much fewer concepts and their use. But high IQ in itself is not a good predictor of intellectual creativity. There are high IQ people with high rates of apo/epiphenia, who constantly see new links and patterns. And there are high IQ people with low rates of apo/epiphenia who see few new links and patterns.

The same pictures can be made of low IQ minds. The difference is that the maps contain fewer concepts. Lower IQ people simply learn less.

I think people with moderate IQs can be very intellectually creative. They can definitely be witty and innovative. But in order to make any breakthrough in science or philosophy, a certain information handling ability is needed. Without a certain size of one's mind map, there are simply not enough concepts to make connections between. For that reason, I believe genius requires a certain IQ floor. I don't know where it is. Maybe 120-130. Evolutionary biologist E O Wilson once claimed to have had his IQ measured to 123. I think many would agree he was a better scientist than most.

Who wants a genius anyway?

Psychologist Lewis Terman believed a lot in IQ tests. In a study called The Genetic Studies of Genius he tested hundreds of thousands of children born between 1900 and 1925 and picked out about 1500 in the upper-most range. He missed two future Nobel Prize winners in physics: The future good scientists simply didn't have high enough IQ to qualify for Terman's selected group of "geniuses". He didn't catch any future Nobel Prize winners, but he did catch the main writer of 1950s sitcom I Love Lucy, a president of the American Psychological Association, three educational psychologists and over fifty college and university faculty members. He also caught many children whose future occupations would be "as humble as those of policeman, seaman, typist and filing clerk", according to Terman himself.3

Although Terman's study initially had the word genius in its name, most of his chosen study subjects did not turn out to be any geniuses. They rather became well-adapted citizens. Could a better test, including a test of creative thinking, be better at predicting novel intellectual achievement?

I certainly think so. But the question is: Who wants a genius, anyway? Modern Western society claims to value creative thinking. It certainly does so more than most societies in history and in the world today. But it also has its limitations. When people think freely enough to challenge political orthodoxy, they are no longer highly valued citizens, whether they happen to be right or not.

In every society, there is such a balance between free thinking and right thinking. On the one hand, societies need people who can solve problems creatively. On the other hand, societies need to stick together. If people can't agree about for example which religion is the only rightful religion, they will have difficulties forming an effective army. Consequently, every society punishes intellectual dissent. Some do it less, some do it more, but all of them do it.

For that reason, I'm convinced there has been an evolutionary trade-off between social docility and intellectual creativity. I guess that in more densely populated, highly civilized areas, social docility has been more selected for. Individuals had little agency and the punishment for any transgression was harsh. Pre-modern Japan could be one such example. European Jews lived in a kind of opposite situation, halfway inside, halfway outside society. In their daily work they needed to operate creatively in a more or less hostile environment. Such an environment should have selected for creative thinking more than most environments.

The mental illness theory of creativity builds on the fact that unusual levels of creativity are more common among people with genes for mental illness, especially schizophrenia. The idea is, more or less, that on the one hand, being creative is good, but on the other hand, the same genes can make people mentally ill. I don't say this theory is wrong. I just think mental illness is far from being the only factor in human evolution that counteracts creative thinking.

Let's think about thinking

Most of what I have written above appears pretty basic. I'm a bit amazed that I need to tinker with obscure concepts at the fringe of psychology in order to describe the basics of something as fundamental as thinking ability. I'm not an expert of psychology so maybe I have missed something. But also when I have asked people who are more initiated than me, I haven't got any established concepts to describe how mentally healthy, normal people do it when they think.

I guess that psychology's lack of concepts describing thinking stems from its general lack of interest in thinking. In theory, thinking is a question for psychology. In practice, psychology deals many times more with people who feel the wrong way than with people who think the wrong way. In reality, people who think the wrong way are more of a problem for education and law enforcement than for psychology.

I think that is a shame. Thinking deserves scientific investigation too. Feelings are important, but thinking is our killer app. Without it, we are just mid-sized weak animals without sharp teeth or claws.

For a very long time, I have dreamed of making a simple study: Give people a watch that beeps every fifteen minutes during daytime hours. Ask them to write down what they are thinking of right when the watch beeps. A perfect study? No. But a simple one, to start answering a very basic question: What are people thinking about all the time?

When I was 21 years old I had a job planting spruce seedlings. Day after day, I noticed how my thoughts were depleted. I got an idea: If scientists just knew how people think, radio programs that prompt thinking could be developed. Ordinary radio drowns out thinking. If scientists just knew more about the mechanisms of thinking, maybe working people could be spared some of the intellectual numbness that results from monotonous, physical work.

I don't know how such a prompting program could work. Maybe it could suggest short pieces of knowledge. Maybe it could prompt memories of knowledge acquired earlier. Since I don't know much about how thinking works, I know even less about how to provoke it.

Ambitious research on human thinking doesn't seem to be in the pipeline. But let's start somewhere: How do you do it when you think? How do you perceive that new thoughts arrive? Do interesting thoughts and nonsensical thoughts share the same origin in your mind too? Please write a comment below!

Wikipedia on Kary Mullis

David Robson, The Intelligence Trap, 2019, beginning of book

Wikipedia on Genetic Studies of Genius

Farmers have noted that the less domesticated breeds of cattle (such as Scottish highland cattle) are much better at "taking care of themselves" and "getting out of trouble" than the more domesticated breeds (such as typical US breeds). A conventional breed, when it gets stuck somehow, will stand still and moo until the farmer comes around, figures out how to fix the problem, and if the cow needs to move in some direction to fix the problem, the farmer will hit it on the other side with a shovel. Bos taurus has outsourced its thinking to Homo sapiens. But of course, H. sapiens is a lot better at thinking than B. taurus, and an individual cow is sufficiently valuable to its owner that the human will be strongly motivated to preserve and protect the cow -- it is adaptive for B. taurus to take the outsourcing deal. (And indeed, at only the cost of having 90% of its progeny *eaten* by humans, B. taurus has enslaved H. sapiens to convert vast swaths of land to grow food for cattle, and eliminate competitor and predator species. Perhaps 1/4 of the biomass of land mammals is B. taurus.)

Likely the same thing has happened with humans, especially in industrial culture. You ask "Don't most people who think independently perceive all the noise their minds produce?" Probably many do, and so have given up thinking independently. After all, what are the chances that you'll think of an action that is more adaptive than what a careful application of the conventional wisdom would provide?

So there's likely to be an evolutionary pressure against novel thinking, leading to some sort of stable polymorphism. Further complication comes from the fact that a lot of benefits of novelty are likely externalized, possibly across society as a whole.

Perhaps we can identify specific episodes of history where novel thinking has been adaptive, and where the existing humans did not operate well.

"This is why they complain--they don't _want_ to have brains. Those lead to thoughts, and thoughts cause only suffering. Thus, by asking them to think, you are inflicting the torments of the damned on the previously blissfully ignorant." -- John Rowat, in alt.tech-support.recovery

On problem solving, I like this octopus experiment: I'm not finding the reference I want, but basically, after some well controlled experiments, the researchers determined that about one third of naive octopi, when presented with a jar containing a crab - managed to unscrew the lid and get the crab. The remainder never were able to figure this out on their own. However, all octopi, when allowed to watch a successful jar opening by another octopus, when presented with a jar in a limited time window, could successfully copy the behavior.

This is may be a simplification of that special "something" you are trying to get at. Put another way, there are probably certain classes of problems that only certain people can solve. And no matter how bright, others will not be able to solve the problems without help.

I don't know what you want to call it, but it's there. Feynman noted this type of person as someone with "puzzle drive".