Scott Alexander writes at length about the debate about the risk that a hyperintelligent AI will destroy humanity. The idea is that it could build up its IQ to 100, then 200, then 400, then 800…until it suddenly is able to kill us all.

That line of reasoning raises one question: Why would a computer with a very high IQ be noticeably more capable than decently smart humans in general? After all, people with very high IQs most often are not. There are a number of lists of very high IQ people on the internet. Those lists almost exclusively consist of people who are not known for anything at all except their high IQs and their childhood precocity.

We have, for example, Christopher Langan, born in 1952. He has an estimated IQ of between 195 and 210. He grew up in a very poor family. He claims to have earned a perfect SAT score despite taking a nap during the test. He won two full scholarships but was ejected from Reed University after faulty paperwork. He then held a number of labor-intensive jobs. Langan has developed a theory called the "Cognitive-Theoretic Model of the Universe" (CTMU), which is supposed to be pronounced as "cat-meow". CTMU is supposed to prove the existence of God, the soul and an afterlife, using mathematics. He also supports conspiracy theories, including the idea that the George W. Bush administration staged the 9/11 attacks in order to distract the public from learning about the CTMU.

Richard G. Rosner, born in 1960, has an IQ of about 190. Just like Christopher Langan, Rosner has held a number of odd jobs. In 2001 he sued the TV show Who Wants to Be a Millionaire over the question "What capital city is located at the highest altitude above sea level? Mexico City, Quito, Bogota, or Kathmandu?". Rosner answered Kathmandu, which is at about half the altitude of Quito, but sued the TV show because La Paz, a city not on the list, is the world's highest lying capital. Rosner lost the case. Here is an article where Rosner explains his stance. Rosner has later written and produced for quiz shows on TV and several programs produced by Jimmy Kimmel, including The Man Show, Crank Yankers, and Jimmy Kimmel. He has also appeared in commercials for Domino's Pizza and Burger King.

Michael Kearney, born in 1984, has an IQ of about 200. He started college at the age of six and graduated at the age of ten. He remains there until this day. The reason why most of us have probably never heard of Michael Kearney is that he apparently excels at writing IQ tests, quizzes and college papers but not much else.

Nathan Leopold, born in 1904, had an IQ of about 200. He grew up in an affluent family in Chicago. In his late teens he befriended Richard Loeb, born in 1905. Leopold and Loeb were inspired by Friedrich Nieztsche's idea of Superman and decided that they were supermen themselves. They thought that their intellectual superiority made them entitled to break society's laws. They stole things and put things on fire but no one seemed very impressed, so they decided to murder a younger teenager and get away with it. They planned their deed for months before they murdered 14 year old Bobby Franks, a second cousin to Loeb and a neighbor to his family.

Their plan was not only morally incomprehensible. It was bad even on a technical level. Loeb dropped his glasses where he and Leopold hid the murdered teenager's body. Leopold spoke freely with both reporters and investigators and even told investigators "If I were to murder anybody, it would be just such a cocky little son of a bitch as Bobby Franks." When Leopold and Loeb were arrested, they claimed that they had picked up two women in Chicago in Leopold's car when Bobby Franks disappeared. However, Leopold's chauffeur told the police that he was repairing Leopold's car that particular evening.

The whole thing sounds… stupid. With all those IQ points, couldn't they even make up a water-tight alibi together before they were arrested?

A bifurcated tail

There is doubtlessly a correlation between the result on IQ tests and the elusive concept of intelligence.

Basically, IQ is the ability to see patterns. That ability correlates with a lot of usual stuff: People who are unable to detect simple patterns are in general unable to think. More refined IQ tests measure more than that, like linguistic ability, general knowledge and short-term memory. Those complicated IQ tests correlate with almost any measure of success (says for example this book).

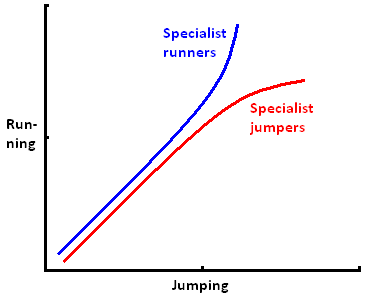

That doesn't mean that it is the ability to recognize patterns that make people think particularly well. Correlation is not causation. Imagine that we run another test and ask people of all ages and backgrounds to first run the fastest they can and then jump the highest they can. I believe we would get a very strong correlation between the abilities to run fast and jump high. We could rather reliably predict people's ability to run fast from their ability to jump high, or the reverse.

Put on a graph this correlation would be a straight line. But only up to a point. Most bad runners are also bad jumpers. And most decent runners are also decent jumpers. This would not hold true for the very top performers. The very best runners and jumpers are highly specialised for either running or jumping. They would not be world class in both categories. The lines for runners and jumpers, moving in tandem for most of the graph, would diverge at the top. The graph would have a bifurcated tail.

It is exactly the same with IQ tests and thinking. Most people who can't detect simple patterns are rather bad at thinking and learning. To test pattern detection ability is a way to detect brains that don't function very well: actually, that was why the first practical IQ test was developed. People who are decent pattern detectors tend to be decent thinkers and decent learners and people who are decent thinkers and learners tend to be decent pattern detectors. But the upper part of the graph, the tail, is bifurcated here too. The people at the high ends are almost certainly specialists. Those who are extremely good at detecting patterns are specialists at detecting patterns. Those who are extremely good at thinking, are specialists in thinking.

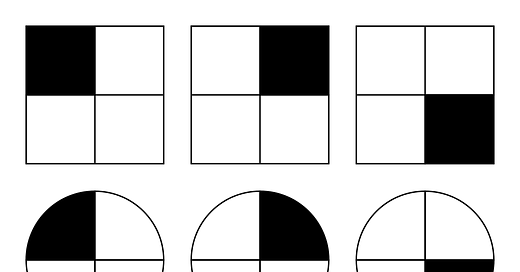

That is the reason why extremely high IQ people almost never get famous for anything else than their high IQ. They are specialists, just like all successful sportsmen. It is highly unlikely that the same person will be extremely successful in two different areas at the same time, also when those two areas are pattern detection and thinking. Extremely high IQ people will always be puzzle specialists, not thinking specialists. Something like this:

A dangerous computer?

In general, people with IQs of 200 don't achieve very much, except solving riddles and learning lots of things. Why should we then expect a computer with a high IQ to be a threat against humanity, when very high IQ people so seldom are?

If "an IQ of 200" means "better than almost all humans on a standardized IQ test", computers already have IQs of more than 200. In general, computers are really good at pattern recognition. In that sense, computers already have IQs not of 200, but of 2000 or 20 000. In a normal IQ test, one task is to repeat a string of numbers forwards and backwards. Computers are almost infinitely better at such a task than all humans.

The problem is that a very high result on an IQ test doesn't mean the same thing for a computer as for a human. If a human is good at detecting patterns, that is an indicator (but only an indicator) that this particular human has an unusually well-functioning brain that is also good at thinking. If a computer scores high on the same tasks it only means that it is… a computer.

People with good computing skills tend to be better thinkers. That doesn't mean that computers can think. They are only very good at computing. And at the same time very good at solving IQ tests designed for humans. Like very high IQ people, but infinitely better and infinitely worse.

A couple of your examples are dubious. Christopher Langan in particular seems like an outright fraud. You could have looked at larger sample sizes, e.g. the SMPY.

OK Tove, you name a number of people here who "have" IQs of 190, 200, and higher. But I don't believe any of them actually have those IQ levels. To be technical, IQ is something one scores, rather than has, but assuming IQ is a trait that one can possess, I still don't believe most of these scores.

There's a rarity chart here that says how common such people should be at https://www.iqcomparisonsite.com/IQtable.aspx which says that IQ 200 is the upper 99,9999999987% of people - in other words, one out of over 76 billion people. You are reporting on the existence of more than one such person, but 76 billion is more than the number of people who have been alive since IQ testing began. The number of such people we would expect to have ever lived is zero.

I do believe that these people are widely reported as having ultra high IQs. And I'm willing to believe that at one point, according to some test, maybe some of them really did score that high, but even that is something I'm not sure of. What I don't believe is that most of them truly *have* an IQ this high.

How would one even design a test for people who are so rare? Wouldn't you need one of these special, one in 76 billion people to be able to design the questions? Most IQ tests have ceilings on them - upper bounds where no one can score above. A common ceiling is 160 IQ. But even approaching these ceilings, the score starts to be less meaningful, so (depending on the test) scores above 150 can be imprecise. https://www.verywellfamily.com/ceiling-effect-1449173

You point out many people with reported IQs of 190, 200, and above have few accomplishments, and argue that, therefore, IQ is more a measure of pattern recognition than thinking ability. But what would we conclude if, in fact, these claims about their IQ were just silly?