Good behavior causes teenage depression

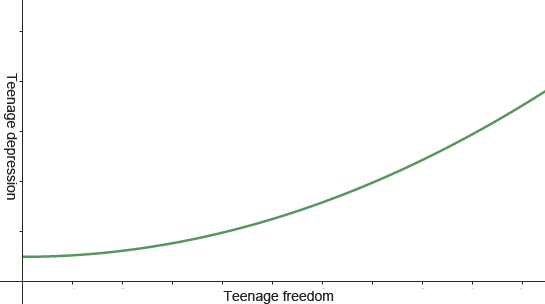

If teenagers are prevented from doing unwholesome things that feel good, some increase in teenage mental distress should logically follow.

Several people, including Zvi Mowshowitz and myself in my article Becky is depressed, have touched the subject: Good behavior might be a reason behind increases in teenage depression. Psychological distress among teenagers is up. All kinds of behavior considered unwholesome, from drinking alcohol to having sex and getting pregnant is down. Zvi cites a number of statistics from the Center of Disease Control, and the numbers are clear: During the last 20 years, teenagers' lives "improved" with less alcohol consumption, less sex, less pregnancy and more adult supervision. At the same time, teenagers' self-rated mental well-being plummeted.

I'm not the first to ask the question: Is that only a coincidence, or does an excess of adult-regulated behavior somehow lead to teenage depression? But I haven't seen any elaborate attempt to actually answer that question. I think that logically, the answer should be yes. I mean, why do people do stupid, short-sighted, unwholesome things in the first place? Why do they drink alcohol, why do they do drugs, why do they have irresponsible sexual relations, why do they perpetrate senseless acts of hooliganism? Because they think it is a great idea? Most probably not. They do it because it makes them feel better than otherwise.

The common narrative is that when teenagers have good lives, they feel better. When they have bad lives, they feel worse. But I think the question is much less straightforward than that. When surveys ask teenagers how they feel, they ask them how they feel here and now. So when someone asks teenagers who frequently do some unwholesome things how they feel, many of them will honestly answer that they feel rather well. They might not have ideal prospects for the future, but here and now, they don't feel that bad. At least, they are not depressed.

Then try seriously to take away every single opportunity for teenagers to do shortsighted, hedonistic, unwholesome things. Logically, a number of teenagers who would have done unwholesome things and felt fine at the moment, simply get depressed and anxious. Their means to make themselves feel good was taken away without being adequately replaced.

It could be that teenagers' lives have become objectively better. Some who would have been victims of crime, overdoses and addiction will escape that fate. Some who would have become teenage parents are free to invest in their education and their life skills until they are more than 20. Objective, long-term wellbeing and subjective, short-term wellbeing are not the same. If researchers ask teenagers how they are feeling here and now, many teenagers who pursue a hedonistic short-term strategy will answer that they feel rather well. If those hedonistic, short term strategies to feel well disappear some years later, a number of the new teenagers will answer that they feel anxious and depressed. Their opportunities to feel good here and now have been taken away by a well-meaning society.

I don't know how big that group of teenagers is. But I'm sure it must exist. Take away people's means to cure themselves of the psychological distress they feel here and now, with no matter how well-meaning intentions, and a number will actually feel that psychological distress here and now.

The U-shaped curve of freedom

I think that logically, the relationship between the freedom teenagers enjoy and the level of psychological distress they experience should be U-shaped.

If teenagers, or any group of people has too much freedom, anarchy will ensue. It will be the rule of the strongest and everyone else will be their victims. Most probably, those victims will have high levels of psychological distress. In a society with high levels of violent crime or in a school with high levels of bullying, most people aren't really free. They are just at the mercy of the most ruthless people.

Also, if people are free to be entirely hedonistic, they might see their friends die from drug overdoses and accidents and violence. Too much freedom doesn't make people optimally happy. Especially not immature people like teenagers.

But the other side of the curve, no freedom at all, doesn't make most people happy either. If contemporary Western teenagers have little freedom, that is because every teenager is obliged to take the recommended slow-life strategy based on diligent studies. Decades of observation showed that teenagers who studied hard and single-mindedly, postponed family formation and did not take recreational drugs to any higher degree got better lives. For that reason, policy-makers figured out that if just all teenagers could be made to take exactly that route, all teenagers would have better lives. So Western society did their best to stamp out what was seen as social ills.

I think they failed to think of one thing: People are different. The foremost reason why some teenagers did so well probably was that they could. They were psychologically and intellectually adapted for studying, working extra jobs, having sane friendships not based on stimulants and so on. The teenagers who neglected their studies, drank too much, did drugs and got pregnant too early probably mostly did so because the recommended path didn't suit them. For some reason, they felt they couldn't both take the recommended path and be happy enough. So they took a path that wasn't recommended, but available, and which kept many of them out of depression.

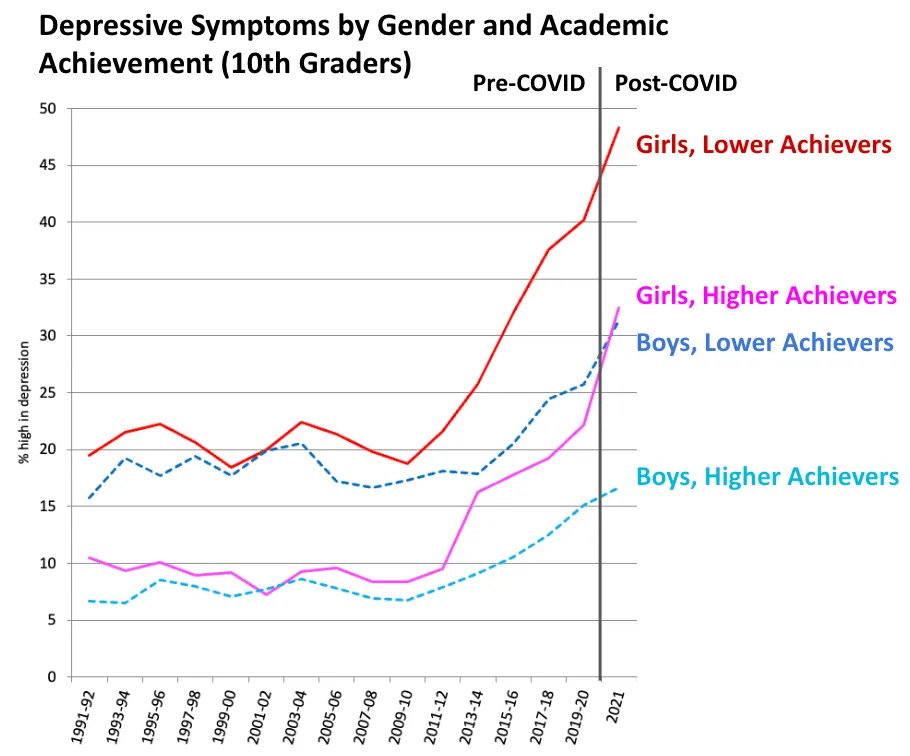

Since that path wasn't a rational way to build a good life, society did its best to remove it. What happened then? All the teenagers who previously would have failed to take the wholesome path, became happy, well-adapted students? I think a statistic from Jonathan Haidt's team indicates the opposite: They became depressed.

Teenage depression disproportionately hits against the teenagers who are the least interested in and the least adapted to the lifestyle society recommends. The low-achieving teenagers who are the most depressed would probably have been the most interested in alternative lifestyles, had there been any left.

A golden age?

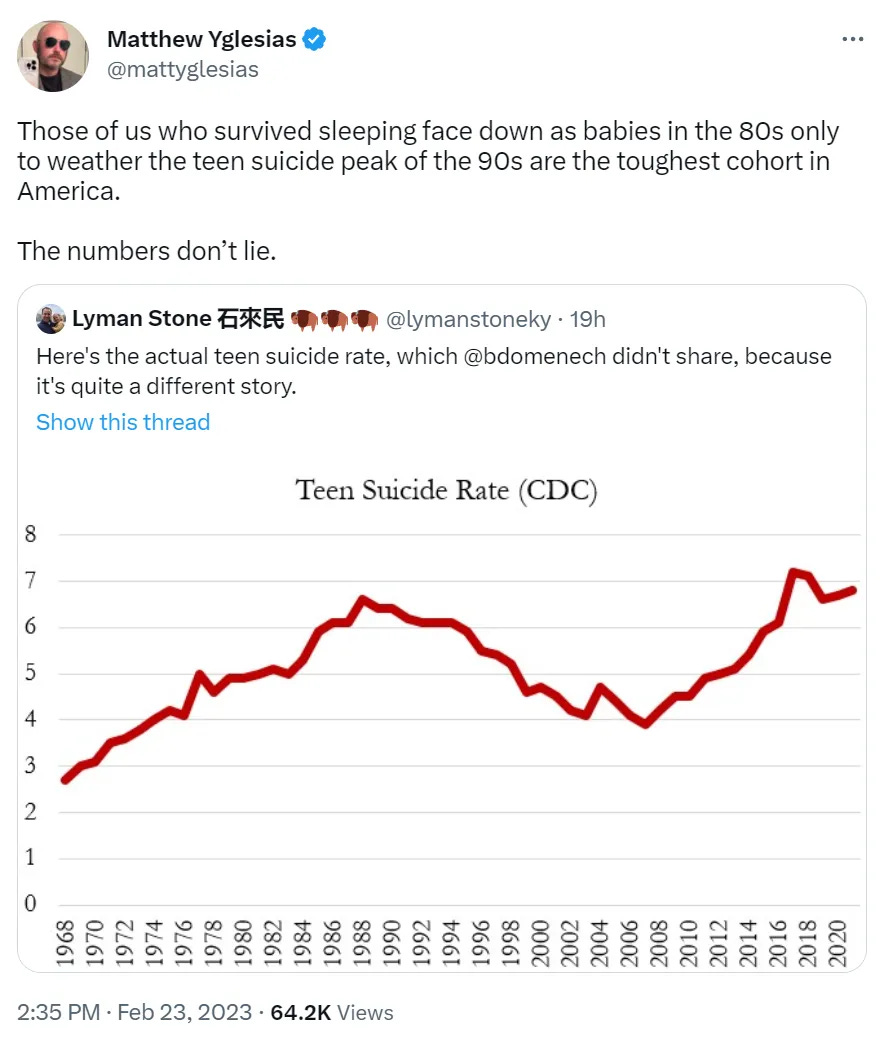

My guess is that when teenage culture first developed, in the 1960s-1980s, society was too far right on the U-curve. If we look at suicide rates among teenagers, they increased until the 1990s. It could be that teenagers then were freer than what was optimal. Alternatively, it could be that society repressed their subcultures the wrong way, for example with repressive and counterproductive laws against illegal drugs.

Between the mid 1990s and the late 00s, teenage suicide was on a comparatively low level. Reported teenage psychological distress was also low compared to now. Partially, new psychotropic medications of the SSRI type are to be thanked for the decrease in suicide and depression: Fluoexitin was approved by the FDA in 1987, a year before the peak in teenage suicide. Other types of SSRIs then followed throughout the 90s. It could be that without SSRIs, the current rise in teenage mental distress would have started earlier. Many of the cases of depression and suicidality in the 1990s could be treated with SSRIs, until the amount of teenage mental distress became so overwhelming that no psychotropic medication could stem it.

Should we then assume that the 90s and 00s were a golden age at the bottom of the U-curve? Society had stamped out the worst social ills that unnecessarily dragged people into misery. But it hadn't yet stamped out all the choices teenagers had. Most teenagers went to school; they weren't out on the streets fending for themselves. But those who didn't like school much could spend their schooldays gossiping and bullying: Anti-bullying programs hadn't successfully taken away that kind of fun yet. People had sex, but mostly without forming families as a result. People drank alcohol, but most did so only sporadically.

I don't say I think the above is an ideal way of organizing a community. I'm just talking about what lies behind the statistics of teenage mental distress. Statistically, a community where a few people feel miserable and the rest feel OK will have low rates of mental distress. It is the majority that make up the bulk of statistics. Make them feel good and statistics are good, regardless of what makes them feel good.

A new U-curve?

I'm absolutely not sure that the curve between freedom and mental distress always needs to be U-shaped. In some societies teenage depression might be only rising with more freedom, like this.

I strongly believe there is a human nature. If a society is really good at adapting to that human nature, maybe it can get away with imposing strictures on its members and they will still feel fine.

What comes to mind is the Amish. They have an extreme amount of rules, which are often not even logical. Different types of technology are banned or allowed according to the whims of tradition and of those currently in charge (who got in charge through a lottery process). The notions on levels of mental distress among the Amish are diverging. Some say the Amish have lower levels of mental distress than the general population1 Some say it is equal or higher.23

I can find no surveys specifically asking Amish teenagers how they feel (where would those teenagers be found? Amish people quit school at 14). Since the Amish have no internet, I can't collect anecdotes based on expressions on social media. Basically, when it comes to how Amish people feel I have only two sources of information: Books written by Amish people who disliked Amish life so much that they left and books by Amish people who like Amish life so much that they write light-hearted books on their great Amish lives. Only about 10-20 percent of Amish teenagers leave the Amish4, so those who leave are a minority. But those who feel great enough to tell the world about it are likely to be a minority too. Naturally, Amish people who feel so-so can't write books about feeling so-so. That would ruin their reputation in the Amish community.

What I can say is that in mainstream Western society, the curve between freedom and mental distress is very likely to be U-shaped. Modern Western society does not serve human nature very well. It doesn't even try: The main objective of society is not the mental well-being of its citizens, but economic growth and the technological development that fuels it. Instead of creating happiness directly, mainstream Western society has the strategy to enable people to make themselves happy. The deal is that society doesn't provide community and meaning to its citizens. Instead it provides freedom and prosperity that enables people to find their own meaning and create their own micro-communities.

If freedom is taken away from that equation, it gets gravely destabilized. I think that is what has happened to today's teenagers. They live in a society where meaning and community is not provided, because everyone is supposed to find their own. But they are mostly excluded from that freedom, because the risk that they would make bad decisions if given any meaningful choices is deemed too high.

Inventing choice

If current teenage mental distress is caused by a lack of choice, the question is: Is there any way society can offer teenagers more choices? Ideally, there should be ways of life that doesn't impose high levels of externalities on other people and the future of the teenagers themselves.

In metropolitan areas, I don't know. Space is so expensive there, that people who don't take the maximally productive path can hardly afford to breathe. But in more rural areas, things could be different.

I get to thinking of one particular person here: Kaleb Cooper. Anders said I shouldn't use Kaleb Cooper as an example, because Americans don't know who he is. If so, I think it is time to change that fact. Kaleb Cooper is the main star of reality TV show Clarkson’s Farm. Famous British motor journalist Jeremy Clarkson bought a farm in the English countryside and ended up farming it himself. As famous people tend to do these days he made a reality TV show about his experiences. While Jeremy Clarkson is the main character in his own TV show the breakout star is doubtlessly Kaleb, the farmhand who already worked on the farm when Clarkson took over.

There are obvious reasons behind Kaleb's popularity. He is funny and charmingly local. He has never been abroad, never been in an airplane and until recently he had never seen a revolving door. Instead he has put his efforts where he lives, focusing on buying a farm of his own.

But I think there is also another reason behind the enthusiasm for Kaleb: Kaleb symbolizes the fact that young people, at least some young people, can still carve out a life of their own. Not being from a farming family himself, Kaleb had to earn money to buy his own first tractor at 15, which he used as a contractor. He officially left school at 16 and before that, he seems to have slept through many lessons: His lack of general knowledge is one of the highlights of the show. He had never heard of Moses. In a later episode, he revealed a lack of understanding of the expression the 20th century (I agree, it's a stupid expression). In his book The World According to Kaleb (2022) he also reveals that he had no idea of who was Charles Darwin. Clearly, Kaleb prioritized farming over studies.

And he is doing just fine. He has a job and he is good at it, he has a small farm of his own, a pregnant fiancée and a two-year-old son. He earns enough to frequently go to the hairdresser to try new hairstyles. Kaleb is a young person who chose to do something else than studying hard and participating in the mainstream status game. He very much got away with it.

I hope there are more such role models to come. All young people are not the same. Everyone can't take the alternative that society deems the best. There needs to be second best and third best alternatives too.

The fact that teenagers felt better a generation ago doesn't necessarily mean that teenagers were better a generation ago. Feeling good enough is not the same thing as living a socially responsible and sustainable life. For that reason, the past is not an ideal. It is just a source of inspiration that can give us more of a key to the nature of the teenage mind.

Gregory Lantz, Perceptions of Lifestyle as Mental Health Protective Factors Among Midwestern Amish, 2019, Walden University, Link

Janette M. Mance-Khourey, Assessing Suicide Risk in the Amish: Investigating the Cultural Validity of the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide, 2012, Link

For teenagers born in 1966-75, the Amish retention rate was 15 percent, according to Eric Kauffman's book Shall the Religious Inherit the Earth, 2010, chapter 1

Our culture emphasizes college first for teens and everything else is a distant second and third option if that. We also mature differently. I believe college should have been an option for me at 16, instead of waiting until 18 to do so (and wasting a lot of time those 2 years in between).

Similarly, there are some young couples who are more mature than many at 18, and we shouldn’t shun all younger couples from having children. That’s a taboo subject but we’ve moved the acceptable timeline to have children to the mid 20’s to the later 30’s. Historically, doing so around 18 was common. I speak from personal experience, having partnered with someone from 17 to 27, but cultural forces told us we were too young to have children even though we discussed it plenty. Now at 35 and single, I may not have that option anymore.

I think what I’m trying to say is that we need to allow teenagers to enter society at a much more accelerated rate, for those who are ready, else have them risk depression or risky behaviors. But it’s easier to say “no” to all sex than to teach teens about good relationship behaviors.

According to the media, the current high-supervision child-rearing style in the US became popular among the well-educated middle class around a generation before it became popular among the other classes. You may be able to exploit this to dissect statistics to separate causation between high-supervision child-rearing and other social changes.