Why fertility inevitably sinks in successful market economies

Fertility is determined by culture. But culture is determined by economic forces, making all major cultures take the same road.

First of all: Apple Pie (Things to Read) has organized a survey. He has compiled questions from himself and a few people who are interested in human evolution. I'm one of them. Personally, I'm a big fan of surveys. When Astral Codex Ten organized a survey marathon two years ago, I belonged to that deranged minority that took every single survey. Now I'm asking as many people as possible to take this collaborative survey. If any question appears unanswerable, just skip it. I would also like to ask you to forward the survey to partners and spouses as much as possible, for one particular reason: This corner of Substack seems to skew toward the male side. Some female responses from the outside world would be great.

Now to the blog post about fertility and economy:

Few societies can stand a GDP per capita of more than 10 000 dollars a year without seeing its fertility go down towards replacement level or below. Regardless of culture, almost every society that gets the least rich will see its fertility rate plummet.

It is called the demographic-economic paradox. It is just an observed association: Nobody knows what causes it. Does economic development cause low fertility or does low fertility cause economic development?

I think it is more plausible that it is low fertility that causes economic development than the other way round. It is not completely uncomplicated:

A question of culture

How many children people decide to have is very much a question of culture. Most people are not independent rational decision-makers. Instead, they have children because other people have children, have abortions because other people have abortions and take contraceptives because other people take contraceptives. Most things people do, they do it because their culture tells them to.

A year ago, Anders argued this is the case with Israeli fertility. Israeli Jews are like other comparatively rich populations, except for one thing: There is an influential and growing minority of ultra-religious, high-fertility people. Somehow, the culture of that growing minority is affecting Israeli Jews of all levels of religiousness. The high fertility of non-religious Jews is a specifically Israeli phenomenon. In other parts of the world, like the US, non-religious Jews do not have a high fertility rate. People probably get inspired to have more children themselves from seeing others having many children.

How to build culture?

If culture is what decides people's behavior, what creates culture then? I think a not too wild guess is that it has something to do with elites, or at least with people who are more successful than their peers. Doing what more successful people are doing, whenever possible, is probably a human instinct.

Why did higher-status people suddenly start to have fewer children than lower-status people, then? In pre-modern societies, the relationship tended to be the reverse: Higher status people have more children, because they can afford more children. But in a modern market economy, a new, previously unseen feature arrived: Those who choose to have fewer children become higher status than others just because they have fewer children.

One of the foremost causes behind the economic wonders of industrialism, was that the family unit and production were separated from each other. When a society industrializes, fewer people stay at home and produce together with family members. More and more people gather at workplaces, with people who are there not because they are related to each other, but because they are the most productive together. This kind of arrangement make wonders for productivity. And on average it makes those who choose to leave their families during large parts of the day more successful and richer than those who follow the old ways.

In order to leave home and family for important parts of the day, postponing and limiting childbearing was a big advantage. And not only for women. Men without liabilities are more free to postpone earnings to the future and invest in their human capital here and now. They are more free to move where they can contribute the most to the economy and get paid for it, without having to think of where to house a growing family.

Childbearing was not without problems in the old agricultural society either. Especially upholding social status over generations was a challenge. But the problems tended to be of a longer-term nature. The children of big higher-class families tended to fall down in status. But the parents didn't fall down from having many children. While the children were children, small families didn't look any more successful than big families. To the contrary - in agricultural households, children provided cheap labor.

Enter industry

The transition from agricultural to industrial society changed all that. In agricultural society all propertied social classes worked from home. It was mostly at home that economic values were created. In industrial society, highly productive adults come together during the day and, in best case, create ingenious solutions together. Having children to take care of is an effective way to get left out from this process.

People who had many children at home simply couldn't adapt to the needs of the modern economy as much as people who had no children. That way, high-paying, modern positions were disproportionately filled by people with no or few children, who had little that pulled them away from the most productive and prestigious parts of the economy. Whenever people looked upwards, to the aspiring classes, they saw smaller families than in their own social class.

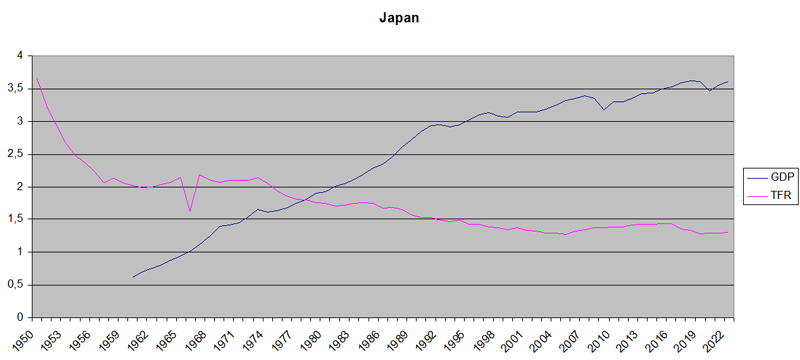

In Western countries, where both industrialization and declining fertility were very gradual processes, it is impossible to see what came first. The two processes seem to have happened slowly and simultaneously. But in East Asian countries that underwent very fast industrialization, fertility rates actually sank toward replacement level before standards of living even approached First World levels.

Comparing GDP per capita over time is difficult and not an exact science. Estimates vary widely. A report from OECD estimates GDP per capita to more or less on equal levels in rich Western countries in the late 19th century and Japan in 1960. According to that report, Japanese GDP per capita doubled between 1950 and 1960, at the same time as birth rates plummeted.1

Apparently, it required much more GDP per capita to lower fertility in the most advanced Western countries than in Japan. Like if when people once knew that low fertility was really associated with socio-economic well-being, the fertility transition could go much faster than when they slowly had to discover that thing themselves.

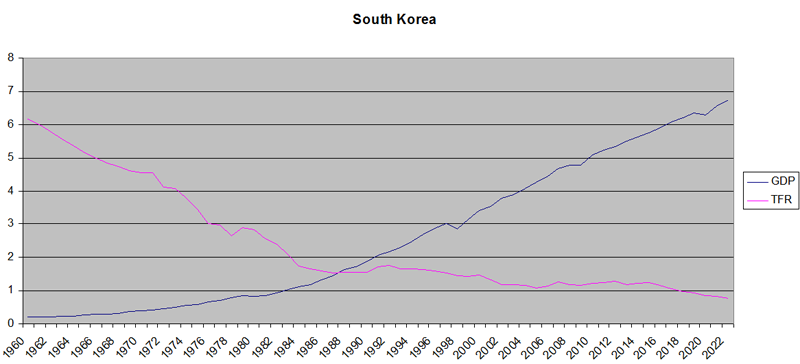

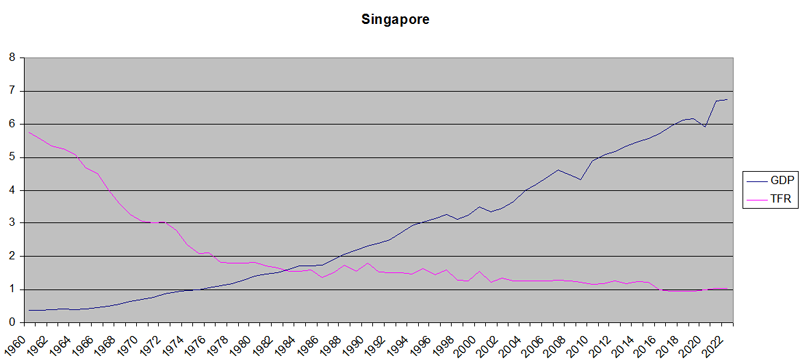

About the same thing happened in Singapore and South Korea, but a little later. Fertility plummeted to Western levels during only one generation, while the economy was still of modest size.

East Asian collectivist culture might have been at play. Government campaigns were not unimportant. Still, it is remarkable that the governments of Japan, South Korea and Singapore managed to nudge people into ceasing having children in one single generation, while they are now failing to reverse the process. Clearly people in East Asia saw an upside in having small families before prosperity had reached them. Clearly they don't see the same upside in starting to have more children now, even though their governments are urging them to.

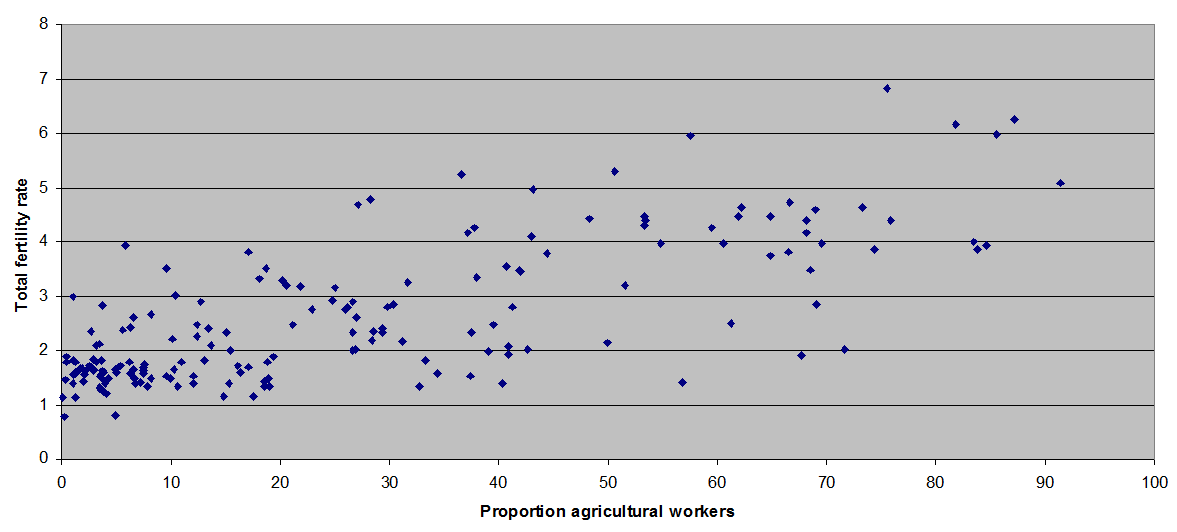

If working from home leads to higher fertility, countries with higher rates of agricultural employment should have higher fertility. A correlation analysis of Wikipedia's list of countries by fertility and employment in agriculture indeed gives a significant correlation. Better than the correlation between GDP and fertility.

It is all very logical. If a country in for example Africa has a rather high GDP per capita because of oil revenues or development aid, that doesn't affect the way people live very much. Higher GDP should lower fertility only when the values are produced by a significant part of the population. Populations maintaining traditional lifestyles should retain high fertility rates, also if there are oil platforms and well-paid aid workers within the borders of the same country.

I suspect this correlation would be even stronger with less misleading statistics. Some countries with high levels of out-migration of working age people have suspiciously high rates of agricultural employment. When an important proportion of the workforce works abroad and sends remittances, disproportionately many people who stay behind will be agriculturalists. For example, when the men emigrate to work, their wives stay and tend the farms. But their main income is not from farming, but from the remittances of an absent husband. Such couples get few opportunities to make children, but can maintain a higher standard of living. This should reinforce norms that encourage fewer children.

Settling for two

If the above line of reasoning is true, why didn't fertility sink to zero among successful people? Probably because that was too much of a break with both prior culture and human nature. Abandoning the ideal of family was too much for most people. Professionals with zero children might have become the best professionals, all else being equal. But they still failed to become an ideal for life.

Until this day, high-status people with two children are considered more successful than high-status people with zero children. In general, having children is still seen as something good. High-status people with four children might be even higher status than parents-of-two of equal professional success. But only slightly so. Not enough to offset the tremendous cost of having four instead of two children distracting oneself from the places where social status is being made.

So the ideal for how many children to have was set at two. Three for the more ambitious and energetic, but two children are considered enough. People seldom ask "why didn't they have another" when people have two children. The answer is too obvious: Two is the most common compromise between the fact that children make life seem meaningful and the fact that they make their parents lose out when competing with non-parents.

Meet the exceptions

In the US, two groups of people stand out: The Amish and the Orthodox Jews. The Amish consist of about 340 000 individuals. Their average fertility rate is estimated to around 7 children per woman of fertile age. Fertility ratio varies per subgroup: the most conservative groups average 10 children. The less conservative groups average 5 children.2

The Amish are exceptions from the rule that fertility sinks in societies where status is created in child-unfriendly environments, for one simple reason: The Amish are forbidden from seeking status in modern, industrial society. They can't pursue any formal education above 8th grade, effectively disqualifying them from the kind of competition that makes people who postpone and limit childbearing higher status in ordinary society. The Amish just happened to have traditions that forbid that decisive factor that limits childbearing - status seeking.

A number of religions encourage childbearing and discourage contraception. But as long as their members are into the same status-game as the contraception-using public, there is no sustainable way to enforce such bans: People do what they need to do, as long as they can do it discreetly. Telling people to have many children while they are competing with people who don't has not been a successful strategy for religious groups wanting to increase their numbers.

Amish traditions happened to both encourage child-bearing and discourage competition with people from low-fertility cultures. That proved to be the right mix to actually enforce a high fertility rate.

But how about the Jews?

The high fertility of the Amish indicates that status-seeking in industrialized society is a great contraceptive. The Orthodox Jews are a different case. In the US, their fertility rate is about 3.3 per adult of reproductive age. I can't find any figures for smaller sub-groups like the New York Haredim, but it is so high that the Haredim are rapidly constituting a bigger and bigger share of American Jews who belong to synagogues.3

Jews have since long been known for lacking rules against making money. They also tend to be urban while the Amish are always rural. And still some Jewish groups manage to uphold high to very high levels of fertility.

Their trick, I would guess, is that the Jews, just like Amish, uphold their own status hierarchies. Among Ultraorthodox Jews, the individuals who make the most money are not the highest-status. Instead, the individuals who know the most about scriptures and follow religious laws the most zealously are. In the Israeli welfare state, a culture where adult males study scriptures while their wives work to support the families has arisen: About 80 percent of Haredi women are employed, but only 51 percent of Haredi men. The arrangement partially builds on heavy childcare subsidies granted for families where the mother works and the father studies at a Yeshiva. Attempts at cutting those subsidies apparently is a cause of intense political debate in Israel.

From this it looks obvious that the Haredim don't share the norms of the rest of society. If being supported by one's wife is seen as entirely normal behavior, then male social status is clearly not determined by earning power.

Amish men work hard in humble vocations that require no education. They refuse to take any government money to support their families. Haredi men in Israel study something that never leads to paid employment, living off government grants and their wives' earnings. Although in many senses opposite lifestyles, the Haredi and the Amish have one thing in common: They don't look up the most to those who succeed the best in the modern economy. One of the communities says "don't study!". The other says "study holy texts, preferably for your whole life!". Although nominally opposite, both lead to an escape from the mechanisms of modern status-building that discourages people from having children.

Only the productive

Another thing that supports the theory that low fertility causes high GDP rather than the other way round, is the fact that fertility remains much higher in countries where oil is the main source of wealth. In the Abu Dhabi Emirate, GDP per capita is among the highest in the world. Still, for citizens the fertility rate is estimated to 3.5, the same as in the heavily agricultural Iraq.

Interesting statistics from Qatar shows that the number of children a woman will have is heavily linked to the number of domestic servants in her household. Female Qatari citizens with no migrant domestic workers had a fertility rate of just 0.39 in 2009. Those with two domestic workers had a fertility rate of about 3.6 and those with one domestic worker had a fertility rate of about 2.5.4 It is like every society has its own norms of when it is suitable to have children. While Westerners feel obliged to abstain from children until they can afford a separate bedroom for the child, Qataris seem to abstain until they can afford someone to take care of the child.

The UAE example indicates that wealth in itself is not enough to suppress fertility under replacement level. It is wealth produced by the hard work of citizens that does. When there is not a low-fertile, hard-working professional class that succeeds better than others, fertility suppression doesn't appear as attractive as when there is such a class to look up to.

Conclusion

People started to have fewer children because focusing on one's job became high-status doesn't sound like a very daring hypothesis. And still, it explains why it is difficult bordering on impossible to raise fertility in modern, capitalist societies: Because however much the government supports families, larger families will always be associated with lower social status (or absurdly high, unattainable social status).

Policies that aim at helping parents in their competition with non-parents through parental leave and subsidized daycare have only helped on the margin. And that is not very strange. Because such policies say that the child-free workplace is the place to be. And as long as people agree with that, most of them will think twice before having another child. However much they are compensated for lost income, they will lose out in competition with colleagues who didn't have that additional child.

The only way to increase fertility among the middle class is to invent norms that move social status from success in the market economy to somewhere more family-friendly. In other words: Fertility can rise and probably will rise, but to a very high cost: the productivity and economic efficiency of the population. The world has never seen any such productive system as capitalism. It is not likely that a system that is equally productive and family friendly will arise out of nothing soon.

Let's face it: Fertility and optimally efficient production are enemies. Both can't be had at the same time. The communities that find the best compromise will inherit the Earth.

Jutta Bolt, Marcel Timmer and Jan Luiten van Zanden (2014), “GDP per capita since 1820”, in Jan Luiten van Zanden, et al. (eds.), How Was Life?: Global Well-being since 1820, OECD Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264214262-7-en

Eric Kauffman, Shall the Religious Inherit the Earth, 2010, 76 percent

Did you watch the birth gap documentary? Apparently fertility goes down not as much because people who have kids have less kids but because more people have zero kids. The distribution of number of kids is more or less the same for all numbers except for zero. Or that's what I think I remember from watching part 1 of that documentary. I hope they release the other parts soon, it was very interesting.

I remember that Emmanuel Todd made a similar observation about the link between declining literacy rate and declining birth rate in his book After the Empire:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emmanuel_Todd