When will psychiatry invent the barcode?

A vision of how to solve psychiatry’s taxonomy problem

A couple of weeks ago I complained that psychiatry has abolished labels without replacing them. For example, formerly there was a label called schizoid personality disorder of childhood. It was abolished in 1994 in the major psychiatry manual. That way, research on schizoid children became discontinued and forgotten. New name - new research. Just start from scratch.

This is not only a problem in the autism corner. Psychiatry as such suffers from a huge taxonomy problem. Until the mid 20th century, autism and schizophrenia were not established as two different concepts. Nowadays some psychiatrists say that autism and schizophrenia are opposites, but a century ago, they were classified as the same condition. By then, schizophrenia had a much broader definition - as if it was a clinical term for “madness”.

This results in a situation where doing research over time becomes more or less impossible. A child diagnosed with schizophrenia in 1970 might today have been called a child with low-functioning autism. And although schizophrenia is a narrower diagnosis now than before, it still seems far from perfect. In this article, for example, researchers speculate that the schizophrenia that high IQ people get is another kind of schizophrenia, observing different symptoms and speculating over different causes.1

At first sight, the solution would be to develop more words. “High-functioning autism, schizoid type”, “low social IQ”, “ high-IQ schizophrenia” or whatever.

But I think that essentially, the words as such constitute the problem. Words simply are the wrong medium to describe a person.

Save the numbers!

An IQ test doesn't put a verbal label on a person - it puts a relative number. A personality test also doesn't put a single label on a person - it puts a series of relative numbers.

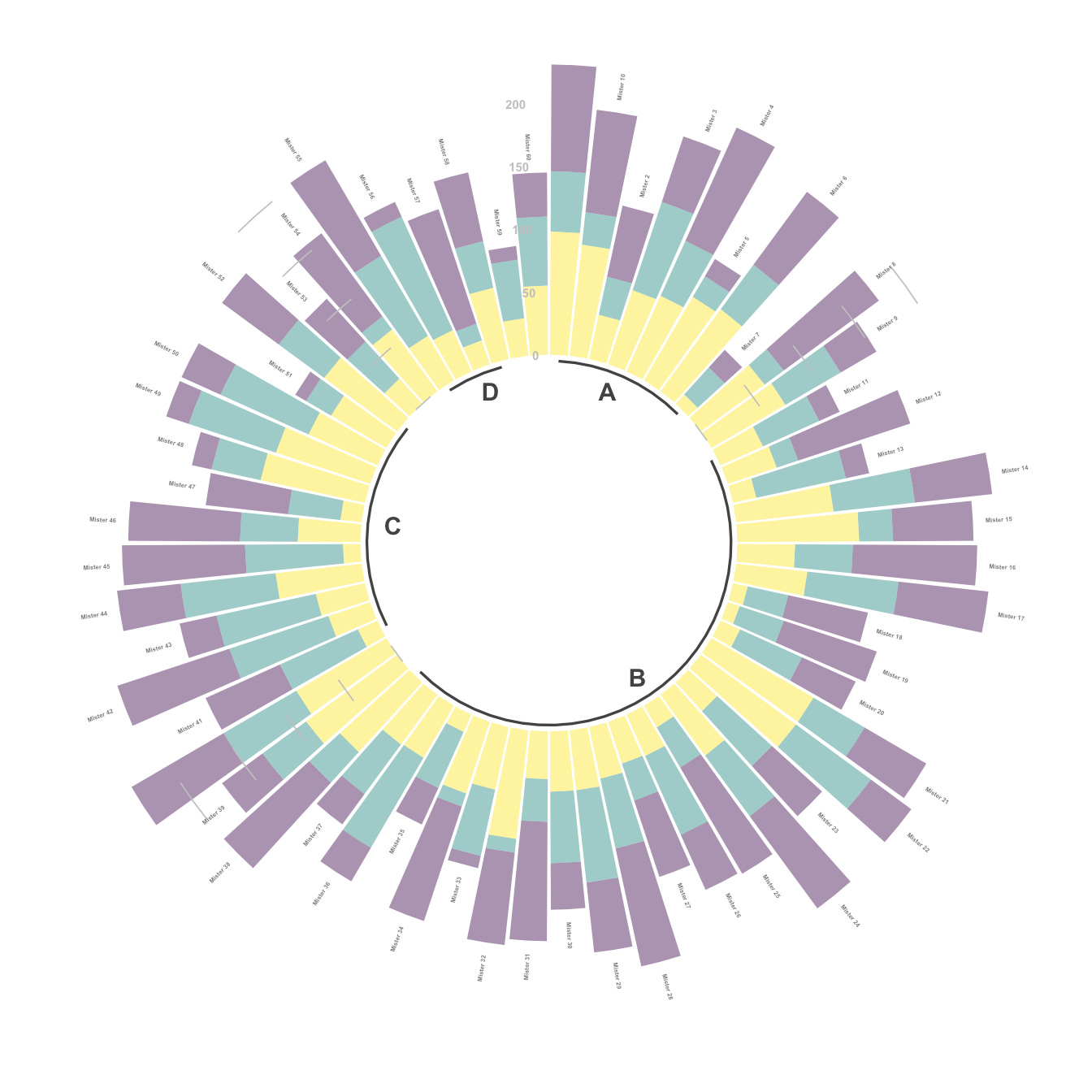

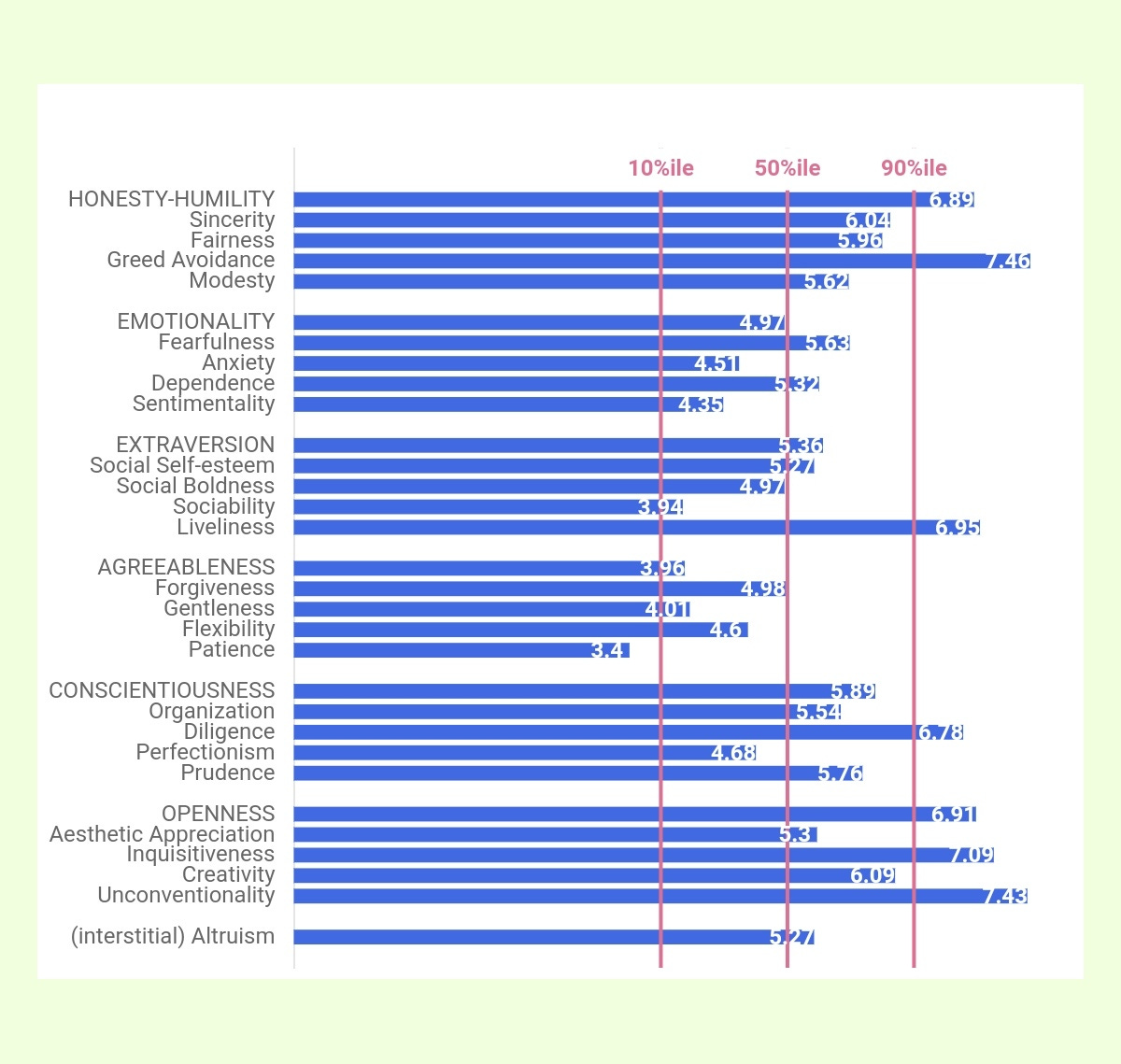

This is my personality according to the Hexaco personality test. It says a few things, but there are a lot of things it doesn't say too. For example, it doesn't say whether I'm afflicted by mental illness and in that case, of what kind. But it could say that, if it was expanded. If I, and people who know me, had gotten many more questions on my ability to pay attention, self control, delusions and so on, this diagram could have been vastly expanded into a long, barcode-like assembly of data.

Having participated in two neuro-psychiatric investigations, I know that they consist of exactly that: A series of questions to the patient, to family members and other people around the patient, combined with an IQ test. The patient and people who know the patient simply answer a leaflet with questions.

So why aren't those answers shown in the shape of a diagram, just as a personality test? As things are, psychiatric patients are asked to answer questions on their personalities and abilities. Then the answers are being churned together according to some kind of secret formula/psychiatrist making educated guesses or both.

Why is that? Why are the answers not saved and presented instead?

Rather than a long bar graph, I would prefer a round one - just for the sake of visibility.

If such a system became established, a trained psychiatrist could easily read the most important traits of a patient’s personality and ability at a glance. It would be as natural and as quick as reading the clock. Like, psychosis at three o'clock, antisocial personality disorder at twelve o'clock, social ability at nine o'clock. For a more detailed result, such a bar graph could be scanned and linked to a text document, like a barcode.

Nothing would prevent psychiatry to otherwise continue as usual. Psychiatrists could continue calling people “depressed”, “schizophreniac” and “autistic” as much as they find suitable, without mentioning any numbers. They would just need to share the information on which they make such diagnoses.

AI without the A

This idea is so simple that thousands of people, outside and inside of psychiatry, must have thought of it. The advantages are so obvious that there must be a good reason why psychiatry didn't invent this decades ago. As things are, it very much looks as if psychiatry is breaking a fundamental rule of science that children learn already in middle school: Reveal your calculations.

Someone inside of psychiatry can certainly explain much better than I can why psychiatry hides its data. My guess is that its practitioners want to make it look more advanced than it actually is. In my experience, when psychiatric practitioners diagnose people, they just administer a niche version of an online personality test, in combination with some observations of a person's appearance and speech. It is supposed to be an art. Be that as it may. But like any art, it is practiced at the expense of science.

In effect, what I'm asking for is not only the removal of psychiatric labels in their current form. I'm asking for the removal of psychologists and psychiatrists in their current form. Replacing them with an AI, sort of. But initially with an AI without an A. Collecting data and presenting it in a diagram is not advanced machine learning. It is a basic statistical operation that was technically possible a century ago.

Long before computers it would have been perfectly possible to create a series of standardized questionnaires. This was actually done in the shape of IQ tests. It could have been done much more. If that had been done, psychiatric research wouldn't have been based on a combination of labels and IQ numbers, but on a whole series of numbers. Scientists themselves would have needed to define their categories, like “people above 130 on the hallucination index”. That way, I think we could have known a lot more about, for example, different kinds of depression and schizophrenia. And the confusion around the autism label of the last two decades would have been entirely avoided. Labels based on visible data simply can't be slippery that way.

With modern information processing technology, opportunities would multiply on top of that. But only if the data is preserved in the first place.

As hard as soft science can get

When I presented this idea to Anders, he wasn't very impressed at all. What if people give different answers to standardized questions over time? he asked. Or in different cultures?

Yes. This is the core problem of psychology: it is subjective. As James Flynn demonstrated in the 1980s, IQ tests are not stable over time. When people get more used to answering puzzles and taking tests in general, they perform better on IQ tests, without being obviously more intelligent than their ancestors in any other sense.

The same problem exists for all psychological tests. They simply can't be made exact. They almost certainly will change over time. But at least I can bet on one thing: no test will change as much in meaning as the autism label has changed during the last three decades. Compared to psychological labels, psychological tests and questionnaires are a wonder of stability.

As the Flynn effect showed, no psychological tests can fully stand the weight of time and social change. Not even the most impressive ones. I don't propose a more data-based approach to psychiatry because it would entirely solve the problem of imprecision and bias. I propose it because more research based on more data is the only way forward.

PS. After finishing this post, it struck me that my proposed round-ish image of a person's soul looks a bit like a snowflake, at least if it is colored in white and light blue. Wouldn't that be a bit symbolic?

E Černis, E Vassos, G Brébion, P J McKenna, R M Murray, A S David, J H MacCabe, Schizophrenia patients with high intelligence: A clinically distinct sub-type of schizophrenia?, 2015 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25752725/

Yours is a radical Idea that psychiatric establishments aren't likely to welcome. "It's too radical, too reductionist, too mechanistic, too insensitive to the many subtleties of varieties of human personality". I could go on and on about all the reasons that psychiatry orthodoxy will come up with and I think there'll be some merit in all of them.

But when all arguments for both sides are laid out, I think yours would still emerge as the most forward-thinking.

One important danger I could think of that's inherent in your proposal is that of reshaping, to a nontrivial degree, the type of people, in terms of cognitive, emotional, behavioral inclinations, who are drawn to the profession. Currently, as well as previously, psychiatry (especially the clinical part) isn't a profession known to hold much appeal for people who are mathematically or statistically inclined. In fact, the predominant intellectual inclination among its practitioners is closer to humanities than science per se. And it's easy to see why this is the case: there's no other discipline in which humans, strictly speaking, are both the subject matter as well as the end object.

In reality and in practice, it's more accurate and appropriate to compare the broad field of mental health subjects to disciplines in humanities and arts than to those in science. Why? It has an idiosyncratic element that often transcends and defies the straight and narrow paradigm eschewed by hard sciences. While there's no doubt that the medical, nosological, theoretical, and diagnostic dimensions of the discipline owe everything to the scientific method, there are other dimensions (praxes, psychotherapy, clinical interview) whose successes depend on factors that do not necessarily emanate from or related to the scientific sentiment. Such factors like empathy, curiosity, interpersonal detachment, relational warmth, attentional patience, preference for people over things, preference for stories over statistics, etc. And it could be argued that this second dimension is more deterministic of treatment outcomes, at least in individual cases, than the former which admittedly could be more significant in ensuring better result when evaluated as statistical averages.

Harking back to the danger I mentioned earlier, what are the chances that adopting the numeric paradigm as against the narrative one won't change the professional landscape of the discipline so much that it ends up losing its 'human soul'? I don't know if you consider this a legitimate critique. And if you do, what would be your response?

An interesting measure you could capture this way is the difference between someone's self-report and how others perceive them. For example, I am sure my mother has no idea how often she comes across as hostile or angry to others.