The philosophy of Peter Turchin

Kind of a book review of the works of Peter Turchin. Cartoons included!

Few writers leave me as ambivalent as Peter Turchin. Fundamentally, his perspective is revolutionary: Turchin studies human populations according to the same principles as animal populations. Almost literally, actually: He trained as a biologist and spent close to two decades making models for the dynamics of animal populations. By the end of the 1990s, he felt finished with the mice and deer and took on the humans instead.1

For that reason, discovering Turchin felt like getting a long-missed piece of a jigsaw puzzle. There have been evolutionary psychologists who study individual humans as a kind of animal for decades. There have been evolutionary anthropologists who study small-scale human populations according to the same game-theoretical principles for just as long. But that perspective has been lacking for complex human societies. At least at a level popular enough to reach me.

Back to Malthus, after all

The basic premise of Peter Turchin's theory is very straightforward: Like any animal, humans multiply until they hit the limit of the carrying capacity of their environment. The amount of land is fixed while an exponentially growing population requires an exponentially growing amount of food. So sooner or later, complex pre-industrial societies will reach a ceiling where the population gets very vulnerable to starvation. A bad year will make a certain part of the population starve to death. Many of those who survive are weakened and more susceptible to diseases. Vagrancy increases because people seek opportunities to survive elsewhere. It all creates an unusually favorable environment for epidemics.

While the producing classes get immiserated by population increase, the elite is expanding too. And it is expanding at a faster rate than the working classes. Since the elite always enjoys better living conditions, they can have more surviving children. When the masses are immiserated, the pressure from below from ambitious commoners will also increase. In polygynous societies upper class men also amass partners, which makes the process of elite overproduction even more rapid.

The expansion of elites compared to working people means that there will be fewer workers to provide for every elite person. Which means that the elite will have to accept lower standards of living and that a certain fraction of the elite will have to fall down to the rank of commoners or die. The latter is rather simply achieved: In most pre-modern societies an important part of elites are warriors, so they tend to start a civil war and kill each other off when things are getting too crowded at the top.

When the working classes are starting to die off, the problem of elite overproduction worsens, because starvation and epidemics hit disproportionately against the working classes. This provokes elites to start wars against each other, assisted by immiserated masses with nowhere to go.

The combined overpopulation among elites and commoners will result in decades of violence, social unrest, starvation and epidemics. The resulting high mortality will thin out the working population until there is enough or more than enough land per person again. Meanwhile, wars will be especially devastating to the warrior-elites. Losers will either be killed off or realize that they have to accept a lower social position. Something that isn't as disastrous as it was: Since so many people have died off, land is plentiful again and labor is scarce. Working people can provide well for themselves. Elites need to pay workers high wages, because otherwise they will just move to a better lord.

That way, a new cycle starts. Commoners are relatively few, elites are even fewer. Elites are also humbled by the unrest they have been through during the last one or two generations and realize that their positions aren't secure. Workers eat well and reproduce well. When this has been going on for a few generations, population numbers have caught up with resources again and a new period of immiseration and unrest begins.

Since I discovered Peter Turchin's books a few years ago, Anders and I have disagreed over how ingenious this theory really is. It is not like Anders contests it. Rather, he says it is self-evident.

It might have been self-evident for him, who reads a lot of history. But I'm not patient enough to do so. And no one explained those mechanisms to me before Turchin. No, not even Anders. So Turchin is one of those writers who has made me see reality in a clearer light.

Peter the psychologist?

Peter Turchin's theory of historical cycles builds on certain assumptions about human psychology. As long as he sticks to explaining pre-modern societies, those assumptions seem rather straight-forward. When people starve and see no realistic opportunities to have children and grandchildren, many of them get desperate and risk-taking. Fair enough. Few people assume anything else. Turchin's assumptions of the psychology of pre-modern elites are also rather easy to accept: People whose job it is to kill people, will start killing each other when their job security and very existence is threatened. Makes sense.

But Peter Turchin means that the same kind of structural-demographic cycles continued also in post-Malthusian times. In 2016 he launched Ages of Discord, a book on American history from the 1820s Era of Good Feelings to 2010. In that book he assumes that the same kind of cycles of popular well-being and immiseration, elite overproduction and elite contraction continues also now that starvation has ceased to be a concern.

That idea requires far more daring psychological assumptions. Saying that people get more violent than otherwise when they see their children starve to death is one thing. Saying that people get violent when they see their relative wages decline compared to those of their parents is another thing. Saying that people who trained as warriors for their whole lives will turn their warring capacity against each other when they need to is one thing. Saying that people who go to university and only get minimum-wage jobs afterwards will get radicalized and sooner or later contribute to a major disruption of society is another thing.

From the background of evolutionary psychology, it makes sense to assume that people keep on to evolutionary strategies that worked in the past, also when those strategies have become obsolete and even counter-productive. For example, if attaining and maintaining social status was crucial for reproductive opportunities in complex agricultural societies, it makes sense if people are still very concerned about social status, even though higher status risks leading to less rather than more reproductive opportunities nowadays. But not even the most hard-lined evolutionary psychologist thinks that humans are completely stuck in the past. Almost everybody thinks that we are both hard-wired and adaptable to our current circumstances. Without actually studying people, we can't know which parts of our psychology are adaptable to current circumstances and which parts are stuck in the past.

Peter Turchin's assumption that modern societies follow the same demographically fuelled cycles as pre-modern societies requires the assumption that human psychology is rather inflexibly hardwired. But Turchin doesn't make a case for that assumption. He just sees things from the macro perspective. He looks at his data and finds it to roughly fit with his observations from pre-modern agricultural societies. Just from that macro data, he seems satisfied to conclude that humans are the kind of animal that reproduces amply in times of cooperation and optimism, strives for elite positions and, when dissatisfied for enough time, causes revolutions and disasters that somehow clears out elites.

I'm especially perplexed that the thinker behind The Structural-Demographic Theory seems so unconcerned about demographics. During the last century, the adoption of contraception changed the demographic landscape in a quite obvious way. Within all economically advanced societies, the Malthusian curse has now been broken, for the first time in history. Population is decreasing rather than increasing, although people are in no way starving. Peter Turchin does not describe that as a game-changer. He just adds low fertility to the parameters that are supposed to show that Western society is in a downward phase of the historical cycle. The idea that this time is different, because demographics have become radically different, is given no consideration.

Jonathan Haidt to the rescue

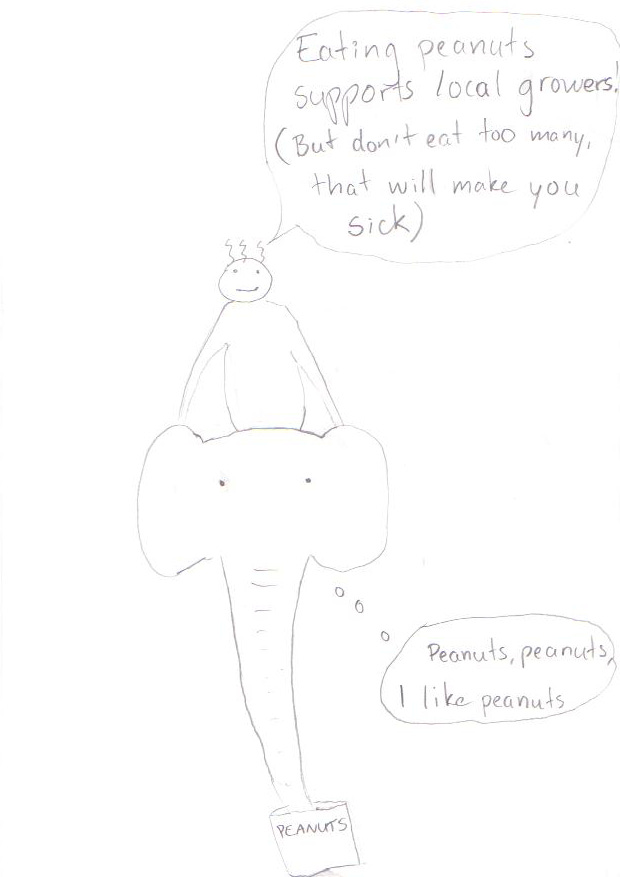

Luckily, Peter Turchin is not alone in thinking of humans as beasts. Psychologist Jonathan Haidt has made a similar explicit analogy, but on the micro level. In his 2010 book The Righteous Mind, he cites ample psychological research that says that humans tend to form opinions based on emotions, and then use their reason to explain why their emotions are right. Haidt illustrates the principle with the analogy of an elephant with a rider, where the elephant represents emotion and the rider represents reason. Mostly, the elephant is in charge. It goes where its animal spirits lead it. The rider's main job is to find intellectual justifications of the passions of the elephant. The rider can sometimes overrule the elephant, when the elephant intends to act clearly self-destructively. For example, the rider can tell the elephant that another piece of cake will make it sick. But in general, the rider's job is to explain why the elephant is acting morally and rationally.

Something like this:

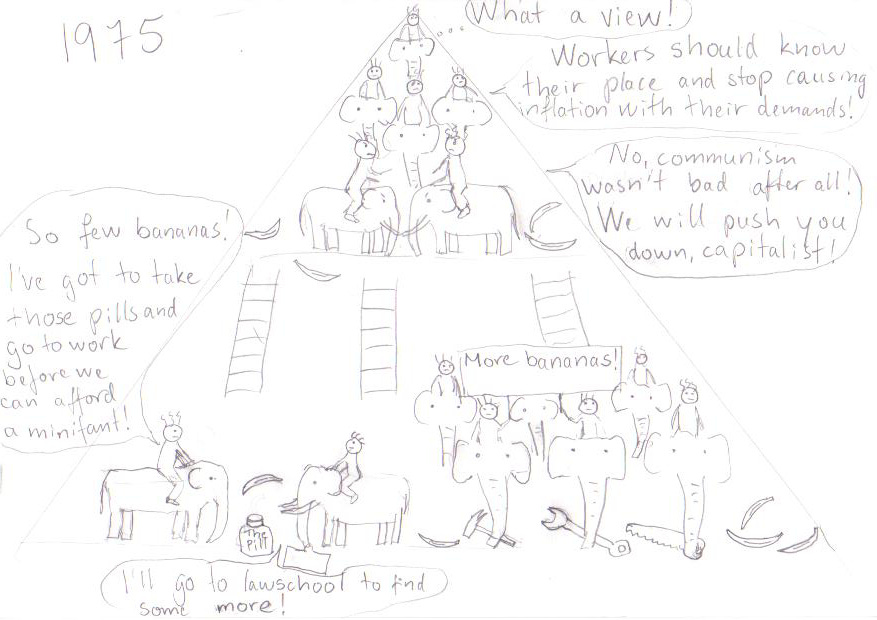

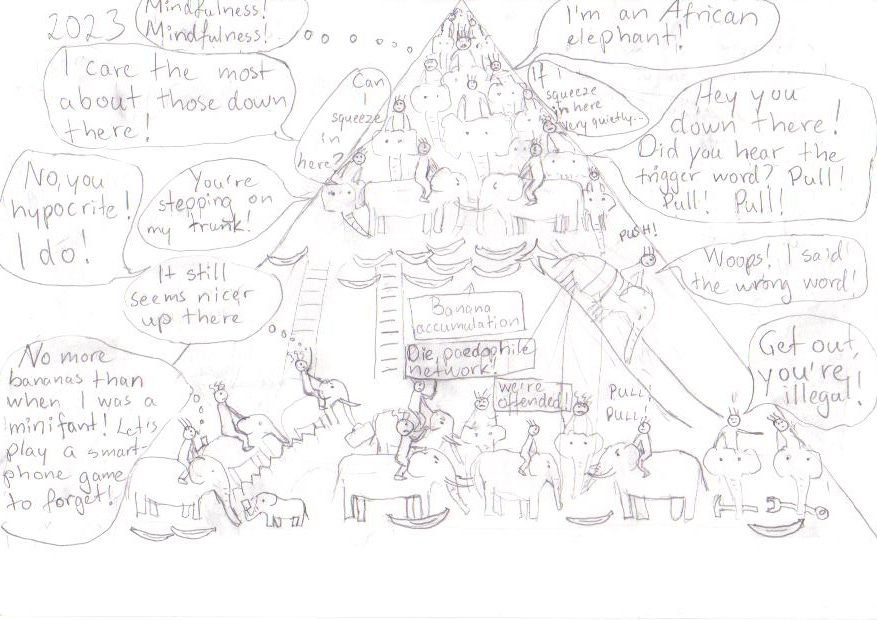

When I read Ages of Discord last spring, I got a picture in my head of Jonathan Haidt's elephants forming a Turchin herd. So I drew the first cartoon of my life: A summary of the current structural-demographic cycle as described in Ages of Discord illustrated by Jonathan Haidt's elephants. It starts after World War 2, about 1950.

The first drawing is supposed to give a picture of Turchin's description of American society around 1950. The Great Depression has thinned the ranks of elites. Those elites that are left know that they need to cooperate with the rest of society, if they don't want the kind of unrest of the early 20th century back again. People feel fine, on all levels of society. Those at the top cooperate. They are few enough to afford to act cooperatively, because there are many workers to provide for each of them. Those at the bottom are satisfied with their improving conditions and reproduce amply.

The next picture is of American society around 1975. All those children from the first picture have now grown up, flooding the labor market with workers, which makes real wages stagnate. Some workers try to improve their lot through competing for a place in the elite. Meanwhile, the elite people have forgotten that they need to think of the best for society. They are becoming too busy quarreling with each other for the too scarce elite positions to care too deeply about society at large.

The last picture is an illustration of Turchin's description of present-day America. The disintegrative trend that started in the 1970s has continued for 50 years. A larger share of resources is going to elites, making it increasingly unpleasant to be a non-elite person. Thereby even more people are competing for elite places, which makes the elite very crowded and elite places very contested.

So what is expected to come after 2023, according to Peter Turchin's model? More of the same, just like during the last 50 years: More popular immiseration, more competition at the top. If current Western society continues to follow the standard pattern for societies, our society will become more unequal and more filled with conflicts, until any kind of major crisis erupts that leads to a sharp reduction in the numbers of elites. Then the remaining elite people will be more careful and realize that they need to cooperate with society and not only compete with each other. Peter Turchin hopes that the elite will come to that conclusion without too much bloodshed and social disruption.

Great theory - but is it true?

The idea that people form their worldview based on their number of competitors is indeed interesting. If Jonathan Haidt is right that people form opinions based on the way they feel and not based on rational thought, it is also plausible: People who feel squeezed will make up opinions that justify their feeling of being squeezed. The hypothesis is so interesting that it warrants further studies.

Sadly, Peter Turchin himself seems to have no intent on organizing any such studies. In his books, psychological issues get a very rudimentary, superficial treatment. While reading Turchin's latest book, End Times (2023), a strange question popped up in my head: Is this a children's book? The examples and the psychological and sociological lines of reasoning seemed unusually simple for a book for grown-ups. Turchin writes about simple things that everybody knows about: stagnating wages, rising costs of living and competition from immigration and elites who are more interested in their pet-causes than in the well-being of the people. More or less everybody knows that already. At least everybody who is not Woke.

Peter Turchin has made some daring and interesting claims of social psychology. But instead of exploring those claims in depth, he is writing political theory. From my point of view, mostly simple and quite ordinary political theory. On the whole, I can't see the difference between Peter Turchin's political theory and that of any moderate left-wing anti-Woke American.

A world of beasts

It could be that Peter Turchin just had a very valuable flash once. His position as an animal population biologist turned social theorist makes him almost unique. Maybe his background as a researcher of animals gave him the opportunity to explain human history in a light in which it hadn't been explained before, at least not in a way that non-historians can understand.

As someone who has read most of Peter Turchin's books, I would recommend others to read one of the earlier of them, like War, Peace and War or Ultrasociety. The philosophical perspective of humans as a herd of beasts is very interesting and Turchin uses a few useful and, I believe, accurate terms like elite overproduction, intra-elite competition and counter-elite.

However, I haven't gotten much smarter from reading more and more books (and blog posts) by Peter Turchin. Instead, I think the sensible thing to do is to take up Turchin's good ideas about macroevolution and try to combine them with other people's ideas about microevolution. Just as there are macroeconomics and microeconomics, there should be macroevolution and microevolution. If the study of the individual, of small scale groups and of very largest-scale groups can somehow be combined, a lot will be done for the evolutionary theory of human existence.

Peter Turchin, End Times, 2023, first page of preface

Well . . .

Malthus’ idea has been disproven by what’s happened to population since his time.

More food now with eight billion than his time with less than one billion.

See Julian Simon.

Tupy on ‘superabundance’.

Todd Rose on “Collective Illusions”

Thanks

Clay

Don

I agree.

I’m including laziness as the desire to steal, control, use - the resources of others instead of working, developing one’s own.

Like the ancient king wrote . . .

“ My son, if sinners try to entice you, do not consent.

If they say:

“Come with us. Let us set an ambush to shed blood.

We will lie hidden, waiting for innocent victims without cause.

We will swallow them alive as the Grave does,

Whole, like those going down to the pit.

Let us seize all their precious treasures;

We will fill our houses with spoil.

You should join us,

And we will all share equally what we steal.”

My son, do not follow them.

Keep your feet off their path,

For their feet run to do evil;

They hurry to shed blood.

It is surely in vain to spread a net in full sight of a bird.

That is why these lie in ambush to shed blood;

They lie hidden to take the lives of others.

These are the ways of those seeking dishonest profit,

Which will take away the life of those who obtain it.’’

This from three thousand years ago. Not a new problem.

Note the appeal to ‘equality’.

Thanks for comment.

Clay