The Paleolithic Ancestor Model Pageant

Which modern-time hunter-gatherers are the most likely to resemble our paleolithic ancestors?

I recently read a book called The Hadza - Hunter-Gatherers of Tanzania (2010), by Frank W Marlowe. It was an interesting book about one of the world's last remaining populations of hunter-gatherers. There are about 1000 Hadza, and 300-400 of them still live almost exclusively on food they hunt and gather1. They live in a mountain area in Tanzania which is dry and brown half the year and wet and green half the year. Their mode of subsistence is seasonal. For several months every year, they get most of their calories from sweet, fibrous berries that grow on bushes. During the rest of the year they rely on tubers, baobab fruit (which is used as food for small children), honey and hunting. About 27 percent of calories came from meat, but the men eat much more meat than the women2. A little more than half of daily calories are brought in by women3.

Although interesting, the book also made me think of a problem: How relevant are those now-living hunter-gatherers as models for our paleolithic ancestors? In the beginning of the book, we get to know that the Hadza have amicable relations with their neighbors. So amicable, in fact, that some neighbors decide to become Hadza! People from neighboring agriculturalists who don't like to till the land and plant their crops have been incorporated into the Hadza lifestyle and learned the language.4

Wait a minute, I thought. Isn't that what they call a self-selected sample? If people who really prefer to be hunter-gatherers join the Hadza and people, especially women, who like agriculture better become farmer's wives, the people who especially like their lifestyle are over-represented among the Hadza. Especially since this has been going on for at least a century. No genetic study of the admixture of the Hadza and their neighbors was presented in the book.

Also another detail raised my suspicions: The Hadza have resisted all attempts to settle them. Missionaries and the government have tried to convince the Hadza to take up agriculture. It never worked. They stayed for a few months and ate the free food provided as a start capital, then they resumed their lifestyle.5 Presumably they found the hunter-gatherer lifestyle rather satisfying.

Others opted out

This contrasts sharply to other hunter-gatherers I have read about. The Aché of Paraguay for example. The northern Aché had no peaceful interaction with other populations until the early 1970s. After they were contacted, many died from respiratory diseases. Two decades later, those who survived had all decided to take up farming. Some of them ventured into the forest for longer or shorter periods, but they mostly made a living from small-scale agriculture.

In the early 1990s, anthropologists Kim Hill and Magdalena Hurtado observed:

"Since the abatement of the disastrous epidemics they have not had a difficult time adjusting to their new lifestyle, and they do not particularly regret the loss of many of their old cultural patterns. None of them expresses a desire to return to their forest lifestyle despite some naive attempts by well-meaning anthropologists and indigenous rights workers to convince them of the desirability of their former way of life. Their major concerns in life are keeping themselves and their children well fed and healthy, and maintaining high status within the Ache community. They show relatively little concern with their status in the larger Paraguayan society, nor do they seem to care much what most rural Paraguayans think about them or their lifestyle. Their biggest dreams are usually to acquire a shotgun, some new clothes, and perhaps a radio, and to have many healthy children grow to adulthood."6

The Aché did indeed not live an idyllic life in the forest. They had an especially gruesome custom of getting rid of children nobody wanted to take care of through burying them alive "as company" to a deceased adult, most often a male. The children killed this way were mostly girls under 5 years of age, but any child below 13 could meet such a fate. About 14% of all male children and 23% of all female children were killed before the age of ten.7

Also old people were insecure among the Aché. Old men were left behind never to be seen again. A man bragged to anthropologists Kim Hill and Magdalena Hurtado that he had taken as his task to kill old women. He would strike an old woman's head with his ax from behind. All old women were afraid of him, he said.8

One reason behind the gruesomeness of Aché customs could be the relative poverty of their land. For some reason, the Paraguayan rain forest is poor in plant foods suited to humans, or too dangerous for women with children to operate effectively in. Among the Aché, men provided about 87 percent of the calories, mostly through hunting.9

The game was rather small and hunting was dangerous. Many men died, making the sex ratio more even among adults than among children.10 This might explain the need to kill off dependents when an adult man died as well as the low appreciation of old people: There was not much they could do to contribute to subsistence.

The Aché did not become rich from farming. In 1996 they were among the poorest Paraguayans, and there is surprisingly little information to find about them since then. Still, the Aché prefer that lifestyle to the foraging lifestyle of their ancestors. Why did the Aché opt for farming while the Hadza resist it?

I suspect it could have something to do with the availability of resources for foraging in their ecological niche. The Hadza have big game to hunt. For several months of the year, they get most of their calories from berries. They often find honey. When nothing tastier is around, there are tubers in the ground to dig up and eat. Neighboring farmers do not live lives of luxury. Farming in Africa without irrigation has its downsides too. It could be that Hadzaland actually is rather good for foraging and not that ideal for low-tech farming.

The Kalahari debate

Not only the Aché gave up their foraging lifestyle. The Bushmen of Botswana did so too. For a long time, they lived in the Kalahari desert, ruled by neighboring Bantu populations in important matters. From the 1950s to the 1990s they took up farming and cattle herding.

In the 1970s anthropologist Richard Borshay Lee studied the Bushmen of the Kalahari and wrote the book The !Kung San: Men, Women and Work in a Foraging Society (1979), where he held the Bushmen as an example of how our ancestors might have lived. Richard Lee indeed discovered that most people he encountered also had experience in cattle herding. He concluded they had developed herding themselves instead of having learnt it from their herder neighbors.11

Anthropologist Edwin Wilmsen protested against Lee's claims to have studied a stone age people. In his 1988 book Land Filled with Flies, he argued that the Bushmen were since long integrated in the economy of the Kalahari. They had been herders just like the other peoples in the area, but now their role as an underclass made them appear as foragers: They had simply been chased off the better land.12

Personally I think that even if Wilmsen was wrong about everything he assumed about the history of the Bushmen and even if Lee was right about every single fact, I still think Wilmsen's conclusions are the correct ones. Anthropologists habitually overstate the importance of economy and understate the importance of war. The Bushmen knew about their agriculturalist neighbors, worked for those neighbors and, most importantly, did not make war with those neighbors.

Our hunter-gatherer ancestors were not surrounded by agricultural peoples for more than a few thousand years. During that time, agriculturalists expanded more and more, until no areas except the arctic regions and, yes, the Kalahari and some remote rainforests were left for hunter-gatherers. Whether the Bushmen's ancestors were hunter-gatherers or pastoralists, they were surrounded by populations that were more technologically advanced than themselves. Those neighbors are descendants of Bantu expansionists who came from Western Africa and conquered most of the continent. When the Bantu reached southern Africa, they encountered lots of Bushmen. They somehow exterminated or incorporated most of them, but a pocket of them remained in the Kalahari desert. For some reason, the Bantu didn't find it worthwhile to take that piece of land too. Probably it was just too useless to them.13

However our paleolithic hunter-gatherer ancestors lived, they did not live squeezed into inhospitable lands by populations who were more technologically and socially advanced. Because such populations didn't exist by then. They couldn't shed surplus population to richer neighbors as wives and workers. They definitely didn't have headmen from neighboring, more advanced societies to supervise their affairs, as the Bushmen had when Richard Lee studied them.

Enter game theory

People who see previously contacted hunter-gatherers like the Hadza and Bushmen as good models for our past lack one conceptual component: Game theory. Most of our hunter-gatherer ancestors lived in a world where every human was a hunter-gatherer. In most places, too many children were born during good times. That forced groups to expand. Thereby they encountered other groups. Thereby they needed to fight those groups. The winners became ancestors to peoples who eventually adopted agriculture (and to the very few who didn't). Most of the losers' genes disappeared.

Logically, this is how things went when everybody was a hunter-gatherer. When some people managed to create advanced enough societies to tend herds and grow crops, those societies developed higher population densities. That was not always a very healthy lifestyle for the individuals of the early agriculturalist societies. But it was even more unhealthy for hunter-gatherers in the same area: When the opportunities to overcome physical distance is limited, military capacity is strictly dependent on population density. Since agriculturalists have significantly higher population densities their armies would overcome the armies of the hunter-gatherers. As long as they can assemble bigger armies, agriculturalists don't need to be better in any other sense compared to hunter-gatherers. They will win the wars merely through their ability to live more densely. Over a few thousand years, more or less all people in areas where agriculture or pastoralism is possible became agriculturalists or pastoralists. Hunter-gatherers simply couldn't compete.

The few pockets of hunter-gatherers that remained, remained because they didn't need to compete. The reasons vary:

They were so isolated that no one but other hunter-gatherers knew about their location.

They lived in areas with little value for agriculture (or pastoralism). Nearby agriculturalists traded with them, hired them and married their daughters instead of exterminating them, because their areas were of little use anyway.

Hunter-gatherers in situation 1 competed with equals. Hunter-gatherers in situation 2 were tolerated by stronger neighbors. The difference is profound. Societies in the first mentioned situation need to be prepared for war and they need to make sure not to lose the wars. Societies in the second situation face the opposite kind of demand: They actually need to be peaceful and easy going people. If they choose to attack their stronger neighbors, those neighbors will no longer tolerate them. It is a kind of historical selection bias: In areas where more technologically advanced peoples are present, only hunter-gatherers who know how to live peaceful lives within their assigned area and how to maintain amicable enough ties with their stronger neighbors are able to survive. Others will be absorbed or exterminated.

During good years, hunter-gatherers surrounded by other hunter-gatherers experience population pressure that forces them to expand. The neighbors experience the same. For that reason, confrontation is inevitable. Populations who maintain good relations with stronger neighbors don't experience that level of acute population pressure. In some cases they have been squeezed into areas that are rather low quality habitats for humans, so population pressure is limited by the harshness of their environment. They can also shed surplus population, especially young women, to neighbors. Hunter-gatherers surrounded by agriculturalists not only need to be peaceful. They are also provided with opportunities to be peaceful that people in environments where everyone hunts and gathers lack.

A big laboratory

I would say that areas like the Kalahari desert and Hadza-land are no more than big laboratories. That is not too bad: Just imagine if scientists could place humans in a laboratory and say: "Welcome to hunter-gatherer land. Here you are going to live and breed for generations. We will study how you and your children will be affected by your living conditions".

Great experiment, had it not been unethical. And it is not considered unethical to go and visit the Hadza and do just that: Study what happens when a few hundred people are restricted to an equatorial mountain area, living from hunting and gathering and marrying mostly each other. Their condition can give clues about both physiological and psychological effects of the hunter-gatherer lifestyle.

What such an experiment can't say anything about is those parts of life that are affected by outside pressure. A society facing military pressure from neighbors will be fundamentally different from a society facing no such pressure. If there is external pressure, there is an ongoing group selection, where those societies that organize themselves in a way that increases their warring abilities become winners. When such pressure is absent, people have much greater freedom in how to organize themselves. Especially violence levels and social hierarchies are straight out impossible to make conclusions about from societies that did not experience outside pressure to organize for war.

For that reason, creating databases of known hunter-gatherer societies and assuming that our ancestors were like some kind of average of them is just stupid. Instead, different societies should be given very different weight depending on which issue is being studied.

And the winners are…

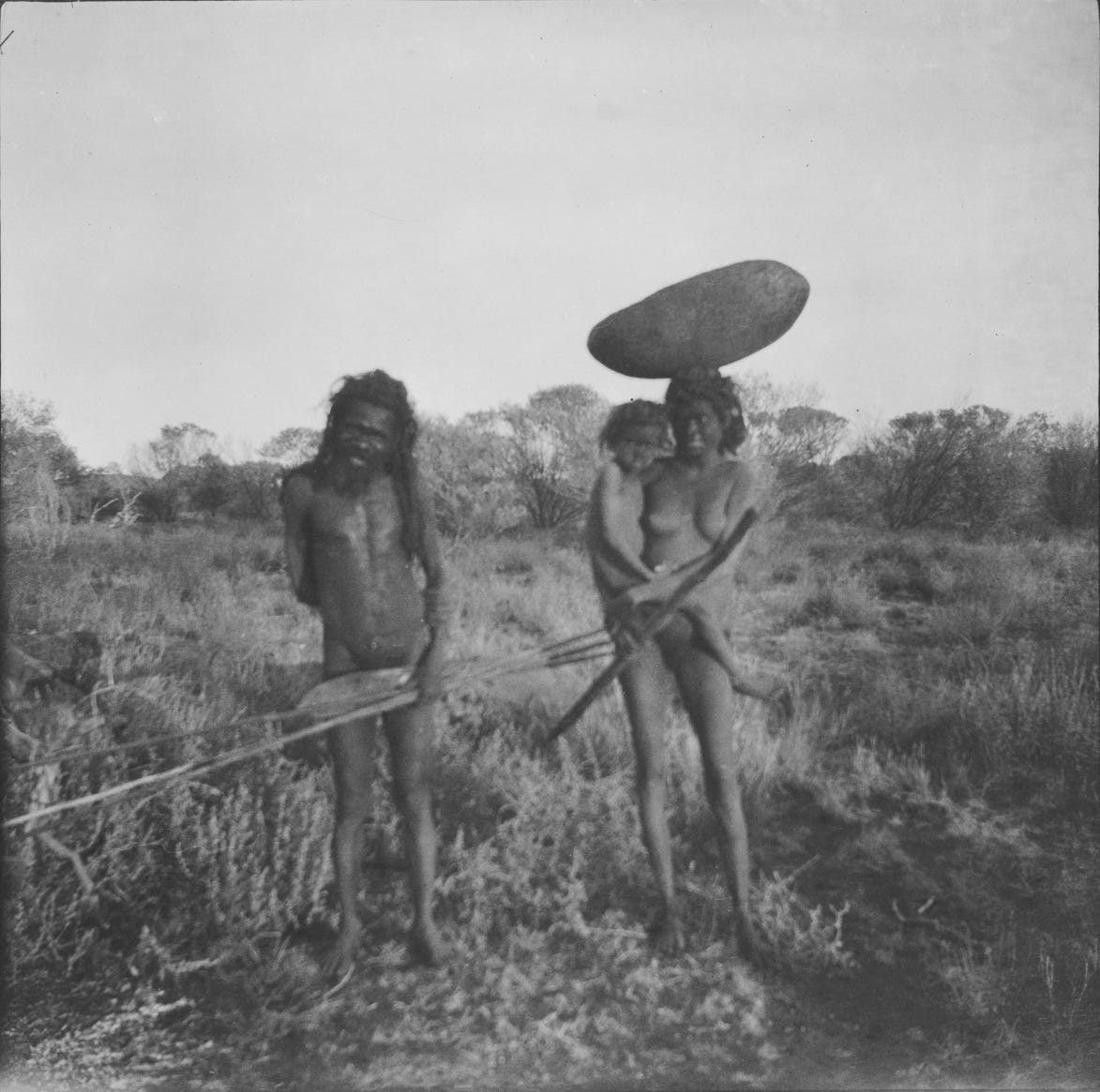

I think the overall winners in the Paleolithic Model Pageant must be the Australian Aborigines. Until the 19th century, they had a continent entirely for themselves to fight over. That continent contained several climate types. Mostly desert, but also some rainforest and some temperate areas. The Australian Aborigines lived and fought over one continent just like our ancestors lived and fought over the entire world.

One disadvantage is that Australian Aborigines ceased being undisturbed hunter-gatherers in the 19th century. What isn't remembered from then, will never be known. Another obvious disadvantage is that Australians were isolated to only one continent. Why didn't the inhabitants of that continent develop agriculture when people on the other continents did so within a few thousand years? Something clearly was different in Australia, otherwise Australians would also have developed agriculture. But they didn't. Since we don't know what prevented them from developing agriculture, we don't know what detail made them different from the ancestors of agricultural populations.

Other good candidates for the prize are isolated rainforest groups like the Aché. The Aché didn't have any peaceful relations with other populations until the 1970s, although they raided farmers' fields for crops. The Aché might be a rather good model for how some of our ancestors lived in isolated environments poor in vegetable foods.

Another candidate is the Inuits. They were forced to remain hunters and fishers because there was little else to do in their environment. Possibly the Inuits could have something in common with those of our ancestors who lived in northern and southern areas during the ice age.

Any other suggestions for the Paleolithic Model Pageant Top 10 Ranking?

Frank W Marlowe, The Hadza - Hunter-Gatherers of Tanzania (2010), page 19

Frank W Marlowe, The Hadza - Hunter-Gatherers of Tanzania (2010), page 127

Frank W Marlowe, The Hadza - Hunter-Gatherers of Tanzania (2010), page 128

Frank W Marlowe, The Hadza - Hunter-Gatherers of Tanzania (2010), 129-132

Frank W Marlowe, The Hadza - Hunter-Gatherers of Tanzania (2010), page 32-33

Kim Hill and Magdalena Hurtado, Aché Life History, 1996, 2017, page 78

Kim Hill and Magdalena Hurtado, Hill and Magdalena Hurtado, Aché Life History, 1996, 2017, page 68 and 434-439

Kim Hill and Magdalena Hurtado, Aché Life History, 1996, page 236

Ache Life History, Kim Hill and Magdalena Hurtado, 1996, page 65

Ache Life History, Kim Hill and Magdalena Hurtado, 1996, page 141

Information from Wikipedia, The Kalahari Debate}

Information from Wikipedia, The Kalahari Debate

Information from Wikipedia, The Bantu Expansion

Australian Aboriginals in 1900 lived much more complex lives than Australians did during the paleolithic. It's often said that they have the oldest continuous culture, but there were massive changes in the Holocene. Take for example the Pama-Nyungan language family, which covers 7/8ths of Australia's landmass. It only spread 6k years ago! And with it, a much richer technological complex. Much of the interior desert was not inhabited before this culture. Or take the Rainbow Serpent, adopted today as a pan-Australian symbol. It spread at the same time, with the same culture.

There are even hints of evolution in that time range, as the skull shape has changed in the Holocene.

Source for that, see: A 150- Year Conundrum: Cranial Robusticity and Its Bearing on the Origin of Aboriginal Australians.

Language expansion: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41559-018-0489-3

Rainbow serpent expansion: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/j.1834-4453.1996.tb00355.x

I'd like to make a tiny offering outside of Substack to you guys. Take Swish?