The bonobo exception

The bonobo is a fascinating creature. But it says little about human history

A week ago I published a theory of female masochism, modeling humans on the common chimpanzee and other infanticidal primates. That post should have included some information about bonobo apes. But it was too long already, so the bonobos get a post of their own.

I expected that one of the main objections to my depiction of our ancestors as violent would be: But how about the bonobo? In reality, no one asked that question in the comments section. Nonetheless, here's the answer!

I think the bonobo developed to become an exception among great apes, just like humans did. I didn't make that idea up myself. I have just adopted it from primatologists Richard Wrangham and Frans de Waal.

A brief history of the bonobo

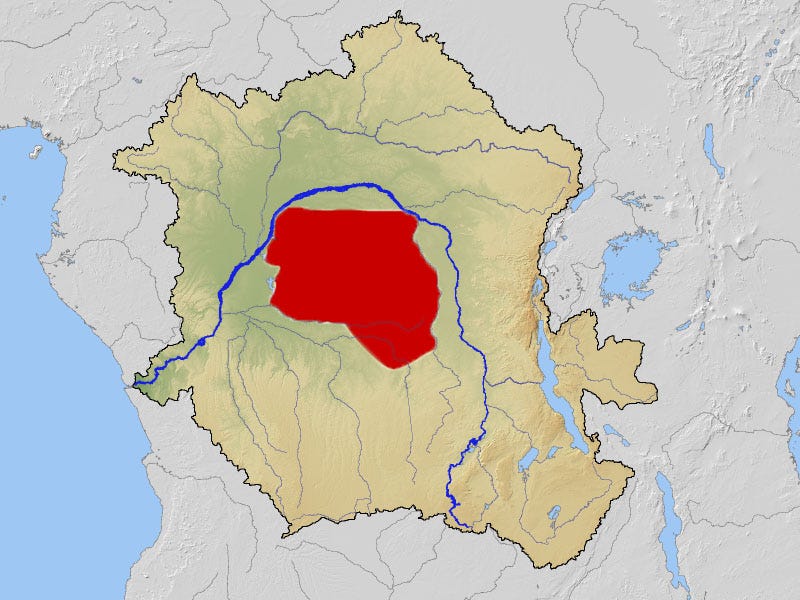

Richard Wrangham explains that about 2.5 million years ago, the climate was much colder and drier. It was so dry that lowlands in central Africa became Savannah instead of forest. The forests receded to mountain areas.

Chimpanzees are a bit flexible in their habits, so they can live both in a rainforest environment and in savannahs - they can live on fruits from trees growing along river banks. Gorillas, on the other hand, can only live in wetter areas. They graze tender shoots and leaves for a living and are thereby dependent on lush terrains. When the climate got drier, the gorillas had to retreat to the mountains. That strategy worked north of the Congo River. But south of the Congo River there are no mountains, so there was nowhere for the gorillas to go. If gorillas ever lived south of the Congo River, they disappeared when the rainforest turned into savannah about 2.5 million years ago.1 (In a newer book Richard Wrangham instead reports the estimate that the bonobo split from the common chimpanzee between 875 000 and 2.1 million years ago, based on genetic studies.2 A new study that sets the time of divergence to 1.29 million years doesn't rule out the formation of the Congo River as a cause of the split. Also Wikipedia mentions the formation of the Congo River as a likely cause of the chimpanzee/bonobo split.)

Subsequently, the climate got wetter again. The savannah once more became rainforest and the chimpanzees who had persisted in the savannah environment became ordinary rainforest inhabitants. When that happened, gorillas descended from the mountains and took up a living in the lowlands north of the Congo River. But south of the Congo River no gorillas remained. That way, the ancestors of the bonobo found themselves in a rainforest without gorillas.3

Population density, as usual

That way, the rainforest south of the Congo River became a brand new ecological niche: A gorilla-free rainforest. That offered entirely new opportunities to the descendants of the former savannah-dwelling chimpanzees. Since all the gorilla food was right there for them to eat, they could uphold a much denser society.4

Among chimpanzees, mothers live rather isolated lives. They can't afford to forage together with several other females, because food is not dense enough. It happens that chimpanzee females create alliances against male violence. But such alliances are rather rare and weak, presumably because females can't afford to live closely enough together to create the trust needed.5

For the ancestral chimpanzees who became the bonobos, things were different. Females could afford to forage and raise their children together. Despite being 25-35 percent smaller than their male counterparts, they could create alliances that could overwin any individual male. In addition to their smaller size, the females faced another difficulty: They weren't closely related. Both chimpanzees and bonobos are patrilocal, which is something unusual in the animal kingdom. At puberty, females migrate into a group of strangers. The males stay with their mothers and brothers.

Still, bonobo females could unite against the brothers. They had something the brothers had less of: Common interests. Among males who don't invest in their offspring, reproduction is a zero-sum game. One male's copulation is the other's loss. Females didn't have that strong conflicts of interest. They could afford to team up more than males, when the opportunity occurred.

Estrus lost

Through the generations, the bonobos evolved physically. They got black faces with pink lips, leaner limbs, smaller heads, less hair and flatter faces than their chimpanzee cousins. Several traits that separate the common chimpanzee and the bonobo are associated with domestication syndrome: Smaller brain, smaller teeth, more paedomorphic skull. Bonobos also retain the white tuft of hair at their rear ends into adult age, while chimpanzees lose theirs when they grow up. In his 2021 book The Goodness Paradox, Richard Wrangham suggests that the bonobos domesticated themselves to be less spontaneously aggressive, just like humans did.6

But the most important change for gender relations was probably the loss of visible estrus. Chimpanzee females get a red, highly visible genital swelling during two weeks out of four. That swelling attracts male sexual interest. The males also seem to be able to smell the most fertile days of a female. During the days of estrus, the male chimpanzees fight over the estrus female and often try to coerce her. Females seem stressed, eat little and often suffer wounds from the fighting.7

Bonobo females evolved to exhibit that genital swelling three out of four weeks instead. Males don't seem to be able to detect during which of those days ovulation actually occurs8. One guess is that it happened because prostitution became an important feature. Also among chimpanzees, males sometimes offer females bribes in exchange for copulations. Among bonobos that became an important part of life, because males had less power to use violence. When females managed to control copulations, males could no longer intimidate females into it. Instead, they needed to buy sexual access. And the longer the period of sexual attractiveness, the more gifts they would receive.9 This might have caused bonobo females to develop hidden estrus. If there is nothing to earn from copulations except sperm and paternal confusion, then open estrus saves energy. But when energy can be earned from copulations, that changes the equation.

With hidden ovulation, the threat of infanticide disappeared. If bonobo males can't tell when females ovulate, they can't tell which children are theirs and not. Also female alliances prevent males from committing infanticide.10

Ape matriarchy?

The social consequences of the lost estrus were far-reaching. Males no longer knew when to pursue females. With 75 percent of all females sporting genital swellings simultaneously, males no longer knew which female to fight over. Among the chimpanzees, the alpha male tries to monopolize all copulations with fertile females. Among the bonobos, that was no longer a realistic ambition. There were fertile-looking females all over the place. And they mated with whomever gave them the juiciest gifts.

Instead, new patterns of hierarchies arouse, with some females more powerful than any male. In bonobo groups, all females are not higher ranked than all males. But the highest female can be higher than the highest male. High ranking bonobo females are also food police officers. They make sure food is divided in a way they see fit (which often means a cluster of high-ranking females eats first).11

The high-ranking females have one important job for themselves: They promote their sons' reproductive interests. Middle-aged bonobo ladies do their best to open up copulation opportunities to their sons. When his mother dies, a bonobo male tends to fall in rank, never to recover it again.12

The hippie ape?

But how about all the sex and the lack of violence? Aren't the bonobos the hippie apes who make love instead of war?

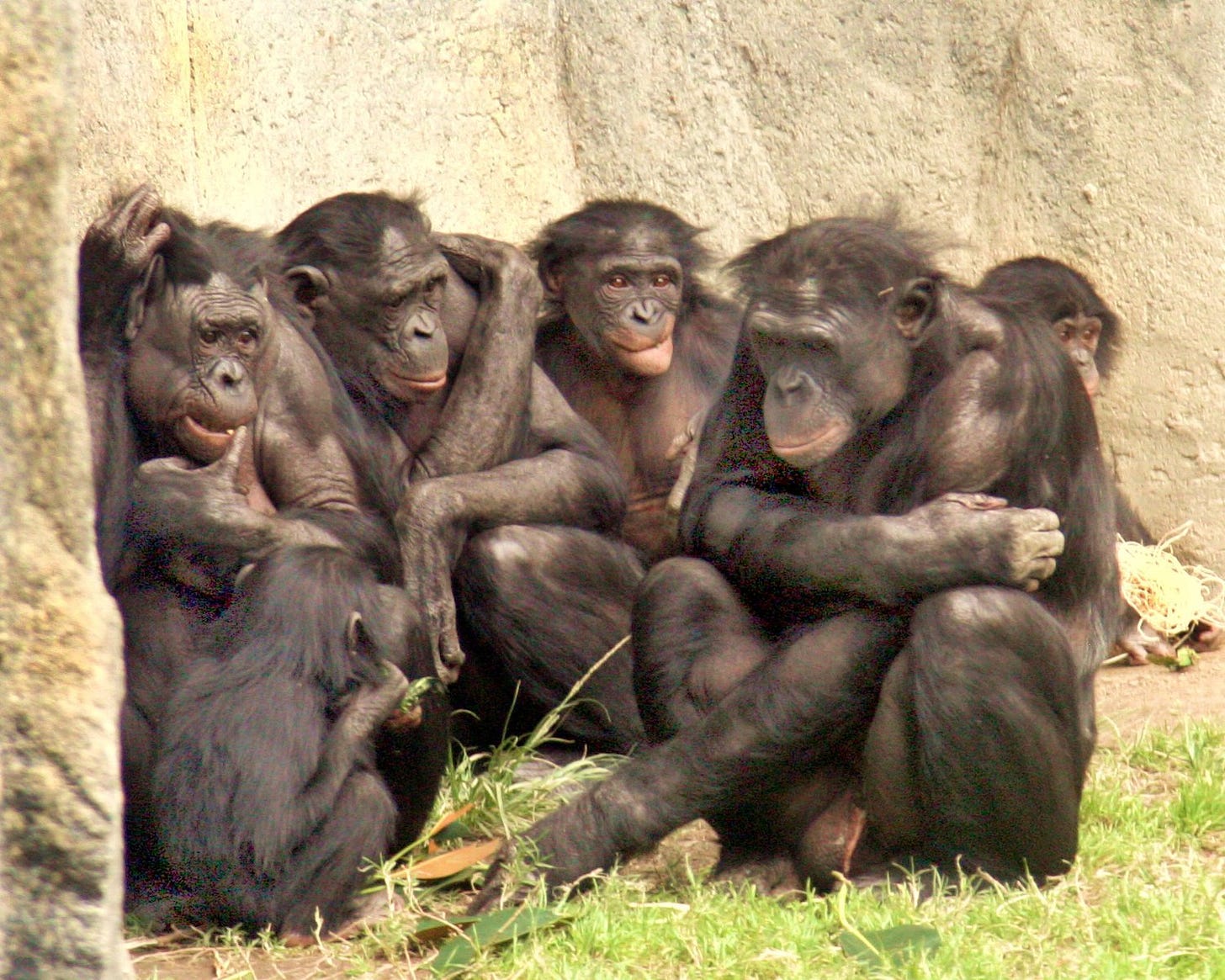

Yes. And no. Bonobos are less violent than chimpanzees, at least in captivity. But they are still much more violent than humans are to their in-group members. Both bonobos and chimpanzees exhibit physical aggression more than 100 times as often as humans do.13

Primatologist Amy Parish reports that in a group of bonobos at Stuttgart Zoo, the alpha female habitually attacked the adult male of the group. Once he was found with his penis hanging from a small piece of skin: presumably the alpha female had bitten it off (vets could repair it again). At Frankfurt Zoo, the females sometimes held the male down and bit off parts of his fingers and toes. Amy Parish speculates that at least part of the physical abnormalities males show at the Wamba national park in the Democratic Republic of Congo stem from female aggression.14

Chimpanzees do such things too, but among them serious violence is mostly a male privilege due to the lack of female alliances (although chimpanzee females can kill other females' children). Bonobos are also less violent to neighboring groups of bonobos. While chimpanzees make war with neighbors, bonobos can sometimes greet bonobos they have never met with curiosity15. However, bonobos normally show aggression toward strangers and smaller groups avoid larger groups.16

Bonobos in captivity initiate sexual activity about every 1.5 hour, while chimpanzees initiate sex every seventh hour.17 The extended sexual behavior of bonobos serves the function to relieve social tension and to create social bonds. Bonobos especially engage in sexual activity when there is competition over food. Females rub their clitorises together. Males rub their penises or scrotums. Females engage much more in sexual activity with each other than males do. Especially low-ranking females. High-ranking females rather seldom engage in sexual activity with each other.

The latter fact strongly speaks against the idea that bonobos have recreational sex for fun. If recreational sex was a privilege, high-ranking individuals would do it more than the lower-ranking. In reality, especially low-ranking females do clitoris-rubbing with each other and with higher-ranking females. Higher-ranking individuals do little clitoris-rubbing among themselves. Instead they concentrate on the real thing when they have sex: Copulations that could lead to reproduction.18At least partially, recreational sex seems to be a way for lower-status bonobos to plead for food and for social approval.

Most animals associate sex with aggression. In many species, especially males tend to become aggressive when they see others mating. The bonobo has turned the causality around. When they encounter a situation that commonly causes aggression, like food to share, they mate. Instead of sex-causes-aggression, the threat of aggression causes sex.

That way, I don't think bonobos have evolved very far from the general aggression-sex association. Just like chimpanzees, bonobos get sexually aroused from potentially violent situations: In my last post, I launched a hypothesis that chimpanzee females feel that unusually violent males are sexually arousing. Bonobo females instead seem to feel that all potentially violent situations are sexually arousing. The lower they are in rank, the hornier they appear. And, naturally, the lower they are in rank, the more threatened they are by violence. That way, I strongly doubt that the bonobos have escaped the sex-violence curse in any meaningful way.

Why we aren't bonobos

The bonobos’ lives do not lack violence and conflict. They also live in groups of genetically related males who defend their territory.19 But compared to common chimpanzees, they appear to be politically correct angels. It would be much nicer to imagine the bonobo as a model for our ancestors rather than the chimpanzee.

Primatologists are skeptical and warn against such wishful thinking. Primatologist Richard Wrangham means that it was the bonobo who, like the human race, pulled away in its own direction. Bonobos developed their unusual, female-led society in an unusual ecological niche: dense rainforest without gorillas.20 Our ancestors did not develop there, but on the much coarser savannah. Our ape ancestors most likely never got the opportunity to create groups with such population density that females could cooperate against male aggression. For that reason it is probable that our ancestors, just like the chimpanzee, were dominated by males.21

According to primatologist Frans de Waal, it was probably too dangerous for a lonely female with children to wander the savanna and search for food. Food was also not dense enough to wander in groups. For that reason, de Waal speculates that it might have been suitable to wander in male-female couples, with females seeking protection from males. De Waal speculates that this might have been the beginning of paternity certainty and male provisioning for children. He suggests that the chimpanzee, the bonobo and humans took three different reproductive paths, which forever gave them different societies. Chimpanzees threaten children who are not their own. The bonobo has no clue about which children belong to whom. Human males developed into providing for their own children.22

Still, the bonobo gives us interesting leads about ourselves. They show that it is possible to take another way from our probably male dominated and infanticidal ancestor. It shows what we already knew, through seeing ourselves: We have potential for both cooperation and aggression.

Our human ancestors took another way than the bonobo. Maybe less sympathetic, but a lot more evolutionarily successful: Frans de Waal notes that both human females and bonobo females have paid a price for escaping infanticide. Bonobo apes have evolved towards almost completely obscure paternity. Since no male knows which children are his, he doesn't threaten any of them. But he doesn't look after any of them either.23 The bonobo females’ constantly sexy genitalia also bleed easily and are cumbersome as they walk or sit.24

Human females got help with providing for the children. This let humans populate the world, while the bonobo ape is strictly limited to a gorilla-free patch of rainforest in central Africa. In that way we human females might be thought of as the most successful. The price we paid was, as Frans de Waal states, our sexual freedom.25 Which, at least in some places, led to the loss of almost all freedom.

In the beginning, there was a species of great ape who lived in the center of Africa. One group of them ended up in an unusually lush rainforest with more to eat than any other cousin. Another group went out of the forest and adapted to life on the savannah. Both groups were successful enough to survive until present time, but in opposite ways: One was washed over with abundance, while the other adapted radically new modes of subsistence. Our shared ancestry brings us together. Our different environments tear us apart. The bonobos show us what we could have become, had things gone a little differently. But they tell us little about who we actually became.

Edit: I'm currently reading a new book by Frans de Waal, Different: Gender Through the Eyes of a Primatologist (2022). In that book de Waal explicitly points out that people should not disregard the bonobo when speculating over the social organization and temperament of the common ancestor. Apparently I interpreted Frans de Waal’s 1997 remarks of human-bonobo differences partially into another conclusion than he intended. In any case, I agree with Frans de Waal that the bonobo shows that another way of being hominid is possible.

Richard Wrangham and Dale Peterson, Demonic Males, 1997, page 222-226

Wrangham 2021, page 119

Richard Wrangham and Dale Peterson, Demonic Males, 1997, pages 222-226

Richard Wrangham and Dale Peterson, Demonic Males, 1997, pages 222-226

Richard Wrangham and Dale Peterson, Demonic Males, 1997, pages 226-227

Richard Wrangham, The Goodness Paradox, 2021, chapter 5

Richard Wrangham and Dale Peterson, Demonic Males, 1997, pages 213-214

Richard Wrangham and Dale Peterson, Demonic Males, 1997, page 212

Frans de Waal and Frans Lanting, Bonobo - The Forgotten Ape, 1997, pages 111-112

Frans de Waal and Frans Lanting, Bonobo - The Forgotten Ape, 1997, pages 118-119

Richard Wrangham and Dale Peterson, Demonic Males, 1997, page 205

Richard Wrangham and Dale Peterson, Demonic Males, 1997, page 206-207

Richard Wrangham and Dale Peterson, Demonic Males, 1997, page 20-21

Frans de Waal and Frans Lanting, Bonobo - The Forgotten Ape, 1997, pages 114-115

Frans de Waal and Frans Lanting, Bonobo - The Forgotten Ape, 1997, page 88

Richard Wrangham and Dale Peterson, Demonic Males, 1997, page 214

Frans de Waal and Frans Lanting, Bonobo - The Forgotten Ape, 1997, page 105

Gottfried Hohmann, Barbara Fruth, Use and function of genital contacts among female bonobos, 2000, Link Sci-hub link

Richard Wrangham and Dale Peterson, Demonic Males, 1997, page 214 and 221

Richard Wrangham and Dale Peterson, Demonic Males, 1997, page 224-227

Richard Wrangham and Dale Peterson, Demonic Males, 1997, page, 229-230

Frans de Waal and Frans Lanting, Bonobo - The Forgotten Ape, 1997, page 136-137

Frans de Waal and Frans Lanting, Bonobo - The Forgotten Ape, 1997, page 106

Frans de Waal and Frans Lanting, Bonobo - The Forgotten Ape, 1997, page 107

Frans de Waal and Frans Lanting, Bonobo - The Forgotten Ape, 1997, page 137-138

You might be misusing the term "not seldom" (both here, and in a more recent post). That means "often," but it's an odd phrase that leaves one wondering if that's your intended meaning.

I think you have a solid thesis in the idea that we have used sex for social bonding, and that especially women may have used it for risk reduction and protection, by having sex with the men that would otherwise pose the biggest risk (thus giving rise to the attraction of "bad boys").

Bonobo's seems to have taken this to next level, using the social bonding effect of sex as a general approach to reduce conflict.

The question is how this applies to humans. According to Frans De Wall:

> "the most successful reconstruction of our past will be based on a broad, triangular comparison of chimpanzees, bonobos, ad ourselves within this larger evolutionary context"

I've mentioned the Pirahãs before:

> "The Pirahãs all seem to be intimate friends, no matter what village they come from. Pirahãs talk as though they know every other Pirahã extremely well. I suspect this may be related to their physical connections. Given the lack of stigma attached to and the relative frequency of divorce, promiscuousness associated with dancing and singing, and post- and prepubescent sexual experimentation, it isn't far of the mark to conjecture that many Pirahãs have had sex with a big percentage of other Pirahãs. This alone means that their relationships will be based on an intimacy unfamiliar to larger societies (the community that sleeps together stays together?), Imagine if you'd had sex with a sizeable percentage of the residents of your neighbourhood and that this fact was judged by the entire society as neither good or bad, just a fact about life - like saying you had tasted many kinds of food" - "Don't sleep, there are snakes", by Daniel Everett

In a triangular evolutionary setup, this sounds closer to Bonobos than Chimps to me.

If we have the potential for both, I guess the real question is what we would want our society to be like. Would we be better served being like Bonobos or like Chimps?