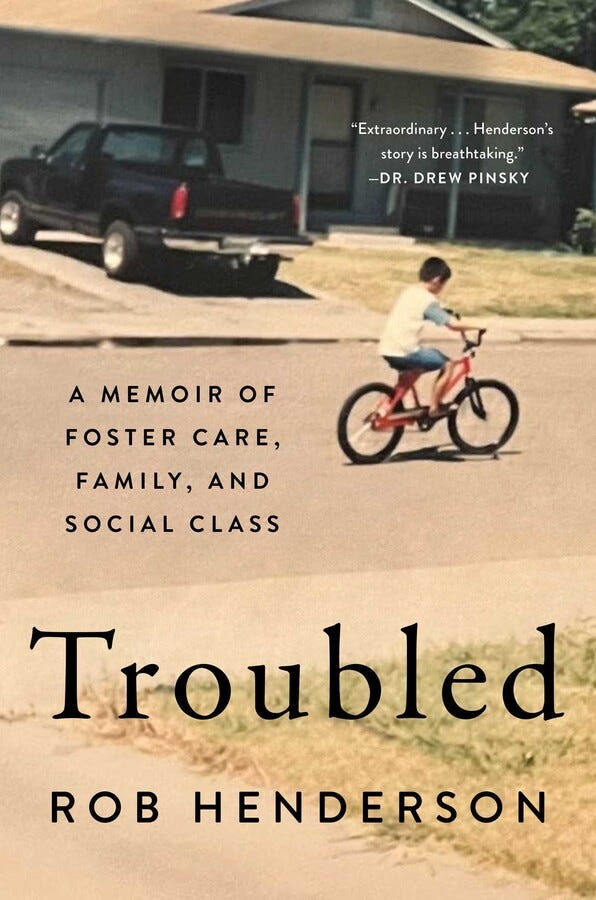

My fellow (and much more successful) Substacker Rob Henderson has written an autobiographical book about his childhood and youth, called Troubled: A Memoir of Foster Care, Family, and Social Class. This book will be released tomorrow, on 20 February. I have had the opportunity to read an advance copy.

The book is about things the author remembers of his childhood. His first seven years are rather briefly described, because, as he writes in the foreword, he doesn't remember much. For example, he remembers little of his birth mother, a drug addict, who he saw for the last time when he was three years old. He then lived in seven different foster homes until he was adopted at age seven, by a working class family in a small town in northern California. Much of the book is about his years from seven to 17, describing what poor kids from broken homes are doing when they are not preparing for college. The remaining part then tells about how Rob could get off that downward track and eventually study for a PhD in psychology at the University of Cambridge.

In one sense, I'm not the right person to review a memoir: I see memoirs as a kind of primary source and I think primary sources are invaluable. People who tell about what they have seen and experienced themselves can never be replaced by intellectuals who analyze and rationalize about how things are supposed to be. For that reason, I can't honestly write a book review around the classical question Is this book worth reading?, because I think it is a no-brainer.

On to something else

Instead, I will take the opportunity to support and elaborate on one of the book’s main messages: That the foster care system fails its mission to give children from adverse circumstances fair chances in life. After having written two books about the Swedish foster care system, I know a bit about it. Although Sweden and America are rather different societies, their respective foster care systems are remarkably similar. Not least in the way they both fail to give foster children stable living conditions.

Rob Henderson describes two types of foster homes: One kind was like a human kennel. It took in numerous children of different ages. The children were given food and shelter but not much more. Even this was limited at times: Sometimes the children had to fight with their foster siblings over what food there was. The social compositions of the foster homes were unstable. Children were placed there and then taken away without warning. The foster parents were often of immigrant origin and didn't speak English as their first language. The children would have been called “neglected” if they were treated that way by their biological parents.

The second type of foster home was the work camp. Most people who become foster parents do it as a job - as a low-quality 24-hour daycare. But some have also found out that foster children can be used as a source of free labor. Rob's last placement before he got adopted was of that kind. He was the only foster child of a middle-aged couple, and his foremost function was to keep the house and the pool clean and to care for the dogs.

I know this work camp type of foster home from Sweden as well. In Sweden, numerous foster children, predominantly teenage girls, have found themselves doing hard labor on commercial or semi-commercial horse stables. Horse stables are usually family-run businesses. They are labor-intensive and not particularly profitable. Some owners have discovered that instead of paying for labor they can get paid for employing a foster child.

For one of my books I interviewed a girl who was used as free labor in a trotter stable. It was a story of the too-good-to-be-made-up type. The girl was placed in foster care because she was homeschooled (forbidden in Sweden) and isolated (whatever that means). But since she was taken from her parents at the very start of the semester, no schooling was arranged for her. The girl, who had been taken from her parents for not going to school and not seeing enough people outside of her family, ended up spending four months not going to school and not seeing anyone except her foster parents and foster sisters with whom she worked 12 hour days in the stable.

The fate of that girl is a good illustration of a system absurd beyond imagination. Shortly after I interviewed her, a policeman was shot to death. The murderer was identified as a 17 year old boy called Sakariye Ali Ahmed. As a 15-year old Sakariye stabbed another boy in the neck so he almost died. He served a year in an institution. Then he was “voluntarily” placed in a foster home. In 2021 he escaped his “voluntary placement” and returned to Gothenburg. For several weeks people, not the least his mother, warned the authorities of his involvement in crime and of his potential for violence. Social workers didn't feel that they had the mandate to take immediate action. They took their time thinking about what to do about the situation. In the meantime, Sakariye killed a policeman.

Swedish society didn't feel strong enough to keep a provenly violent teenager under control. But it was strong enough to keep a girl whose only fault was to disagree with her social workers isolated from society and her family.

I'm not the only one to discover the absurdity of the system. Many people did so before me and many people did after me. Since I published my first book about the foster care system in 2018 I have been contacted by several journalists who have stumbled on a terrifying case of abuse of authority from the social services. They believe they have encountered something extraordinary. I can only tell them that unfortunately they have not found a scoop, they have just found out how the system works. Thousands of Swedish children are subjected to abuse of authority every year. The public just isn’t interested.

From bad to worse

The little science there is points in one direction: The average foster child would have been better off in their birth families. Not because those birth families are especially good, on average, but because the foster care system is disastrous. Governments just aren't any good at taking care of children.

Foster care is like chemotherapy. It saves lives. And it has very severe side effects. Giving it to the right people, and only the right people, is crucial.

That is not being done. Rob Henderson cites a new study that compares outcomes for siblings in families where some children were taken into foster care and some were in from data from Finland. Those who were not did better.1 Another, older study from the United States has used the inherent arbitrariness of the system as randomization. It came to a similar result: Adding another child to the system will on average make that child's life worse.2

Given that the children come from the worst families the authorities can find and move into families and institutions paid by the authorities, those results are remarkable.

I wonder why social researchers who want to study the effects of foster care do not come to Sweden. For historical reasons child protection services are a local responsibility in Sweden, only subject to very vague national guidelines. This gives excellent randomization. Two geographically close, socio-economically similar towns in Sweden can have rates of foster care placements differing up to five times. The only reason is that social workers in the two towns have different opinions on the merits of foster care. Such “natural” randomization would be ideal for science.

The devil you know

The dismal results of the foster care system appear everywhere in the Western world. When a problem is this widespread, it is likely to have to do with human nature, rather than with some local design mistake. I think this is the case with foster care: It is slightly against human nature.

Rob Henderson writes about his years as a foster child:

“If I had to reduce what I felt during these early childhood years to a single word, the only one I can think of is: dread. Dread of being caught stealing, dread of punishment, dread of suddenly being moved somewhere else, dread of one of my foster siblings being taken away. Early on, the dread was sharp—I’d see an unfamiliar car outside or a puzzled look on a foster parent’s face and begin to panic.”

The nature of human children is to attach to certain people in a certain environment: They haven't evolved psychological adaptations for being moved around between unrelated strangers. And adults aren't made for taking care of a child on the orders of an outsider. Being a foster family means being a public family, you more or less agree to let the authorities pry at will into your family. Only a small minority of people are prepared to give up privacy to that degree. That small minority is not necessarily the people who are best placed to take care of unrelated children.

Humans are made to form stable relationships during childhood and foster children are to differing degrees deprived of that opportunity. But I think there is another, more cynical reason too: Because the devil you know is better than the devil you don't know. Children who grow up under an abusive/crazy/incapable parent clearly have a problem. But they have one problem. Sometimes that problem kills them or injures them seriously. But many times they also learn to cope decently with the big problem of their life and have some attention and energy left for growing up like other children.

Foster children, on the other hand, are given new problems time after time. As soon as they learn to cope with one difficult environment, they are moved into another. That alone could explain some of the bad outcomes for foster children compared to children who only live under bad circumstances.

For that reason, I think that Rob Henderson’s book has an important message: Getting children out of foster care is crucial. Not because all birth families or even all adoptive families are very good (they aren't), but because the need for a certain degree of stability is fundamental.

Seeing the invisible

My dealings with clients of the social services taught me one thing: Most people don't have a public voice. Before I got into contact with parents of foster children, I believed that in an open democracy, although every person has very little say, every person also had a roughly equal level of say. The elite obviously has more of a say than the rest, but I assumed that among the masses, everyone was about equally powerful.

After having received a certain number of badly written emails and confused telephone calls from parents who had lost their children to the social services, I started to realize something important: A large part of all people have exactly zero voice in society. Not only little, but zero. Whatever they say, no one will believe them, because they can't express themselves. Even I, who have studied the system and know that many of their complaints are most probably true, am inclined to not believe them. Just because of who they are and how they say things. These people are, in practice, completely lacking a public voice.

Whatever happens to those people will remain unknown until enough people who master public communication start caring. And that can take years or decades, if it ever happens. I have learned not to underestimate what might be going on down under. Everything that doesn't leave physical traces that higher classes stumble over could be going on there, because almost no one who knows what is happening is capable of reporting it.

Rob Henderson is an exception to that rule. He lived through the foster care system and can describe it to the rest of us. That is reason enough to read his book.

Tove, this is a lovely review of Rob Henderson’s book, and it would be a shame if it weren’t more widely distributed.

Three anecdotes:

Our current (NZ) foster care system prioritises placements with kin and provides financial assistance. An acquaintance has fostered a 2nd cousin's child for some years now (since the child was 11?). It's exposed their own younger 'only child' to another whole sprawling set of relatives (for the better . . .and worse?).

As a toddler (3yo?) my Mum thought to 'do good for her community' while providing me with a playmate (my 2, several years older, siblings were born only 11 months apart and had been 'great playmates') by taking in a foster child.

It only lasted a week or two. I don't remember this, but I gather I was jealous. Somehow wreaking the toys allocated to the interloper and refusing to play with him.

In my 20's I worked with a guy who had been raised in the foster system. A good guy though somewhat brittle/vulnerable. At the time I didn't think about it, though perhaps some of that came from his childhood experiences.