Making sense of honor culture

What happens in societies where men take little pride in controlling their own sexuality? Quite interesting things, actually.

I have always struggled to understand the mainly Muslim cultures of the Middle East and Central Asia. And I have always tried to do something about it. At the age of 18 I started to study Arabic. Two years later, at the age of 20, I traveled to Syria and spent three months in Damascus studying Arabic and trying to make sense of what I saw and heard.

I can't say much about my very own anthropological studies without revealing the many mistakes I made. I was far too unprepared. Schooled in the pre-Woke everyone-is-the-same sentiment, I wasn't even prepared for what the phrase different cultures meant.

What shook me the most was the behavior of men. I learned that as soon as a man technically had an opportunity to touch me, chances were that he would. Not in all cases, and there seemed to be zones of exception, like buses (where men instead gave up their seats for women). But essentially, many men behaved as if they themselves believed that they lacked self control.

The behavior of one man especially made an impression on me. Let's call him Ali. Ali worked at the hostel where I lived. He was unusually good at speaking with foreigners, in his unusually good English. Since I had an unusual interest in speaking with Arabs, also compared to other Westerners visiting Syria, Ali and I came to talk a lot with each other. There was only one big problem: Ali couldn't accept that I wasn't interested in any kind of physical relationship with him.

I did my best to explain. I was already engaged, I said. My boyfriend would come and pick me up (true story, Anders actually arrived later in the summer). But nothing I said could impress Ali. As long as other people were around, he behaved normally. We talked about things and that was that. But as soon as he considered us being alone with each other, he unilaterally initiated what I guess should be called gentle foreplay. Gentle, but thoroughly non-consensual: I protested and told him to please stay away from me. He didn't care the least about my verbal protests. The only way I could get him to stop was to start acting violently. I pushed him, and when he didn't react to that, I slapped him. Then he feigned being hurt and actually moved away from me. Until next time he found an opportunity.

If a Western man had behaved like that, I would have been terrified. Western men who act entitled to women's bodies in such a flagrant way are norm-breakers and thereby potentially very dangerous. But there was nothing violent about Ali. He didn't even feign overwhelming passion. He just acted matter-of-factly, as if assaulting me was the most self-evident thing to do. As if it was his job to assault me and my job to push him away.

So I wasn't terrified. I was flabbergasted. And Ali was far from alone. Although I didn't get to know many other Arab men that well, I could clearly sense that his non-consensual, non-violent mindset was very widespread. At one moment, Arab men could talk to me like normal, civilized people. The next moment they could just switch into groping me, without any prior warning. Most of all I wanted to ask them all: “Where is your self respect? Where I come from men don't act like this, because they have some self respect.”

After a while I came to a conclusion: Men like Ali had probably never been taught that they were capable of restraining themselves sexually while alone with a woman. Gender segregation serves the purpose of absolving the individual from such demands. People living in a gender segregated society never need to learn to control themselves like people in gender-mixed societies. On the contrary, they learn that gender segregation is necessary because people can't control themselves when together. After what I could see, there was nothing otherwise wrong with Ali. He was an intelligent and calm person. He had just never gotten the idea that restraining himself while alone with a woman was an option.

In the West, we believe that individuals should be strong in character and control themselves. Sexual self control is a very important mark of honor, for both sexes. People disagree somewhat over where such requirements should end. When should a man finally be allowed to act out his sexual impulses? When he gets an eligible woman over the threshold of his apartment? When he makes her sign a consent app? But I have never heard of any Western subculture where exerting sexual self control in everyday life is not considered an important part of personhood.

Before I went to Syria, I was very well acquainted with one Muslim accusation against Western society: That it is overly sexualized. After a while in Syria, I quietly started to turn that accusation back on the Arabs: In fact, it was they who gave sexuality an outsized importance. They saw sexuality as something much more overwhelming compared to Westerners, who recognize sexuality as a fairly controllable force.

Above the baseline

After a summer in Damascus and some other places in the Middle East, I went back to Sweden. I quit learning, and even speaking, reading and writing Arabic, because I realized that the bulk of my conversations in Arabic would be about with whom I should have sexual relations.

So I left the riddle of honor culture unsolved. Only much later, when I discovered anthropology, I began to connect some dots. Napoleon Chagnon's books on the Yanomamö was an eye-opener. They exhibited another society with low levels of sexual self control. When I visited the Arabs, I considered them illusory. If they just knew that men and women actually can intermingle without having sex all the time, they wouldn't have to cripple their society with gender segregation, I thought.

Napoleon Chagnon explained the other side of the problem: Given the assumption that men can't restrain themselves sexually, or have no interest in restraining themselves sexually, a strong social structure actually is of utmost importance. In his book Noble Savages, he writes:

“Regardless of their marital status, most Yanomamö men are trying to copulate with available women most of the time, but are constrained from doing so by the rules of incest and the intervention of some other man with proprietary interests in the same women.”1

That is, Yanomamö men did not pride themselves over their sexual self control. Sexual self control was just a necessary evil in order to avoid getting killed. Napoleon Chagnon writes:

“It seems that the primary source of conflict within stateless human groups is young females of reproductive age who have neither fathers nor husbands to safeguard them. They constitute a major cause of potential instability and strife among the Yanomamö: aggressive adult males between the approximate ages of 15 and 40 constantly want to copulate with them and/or appropriate them for their exclusive reproductive interests. They are a source of conflict in Yanomamö communities and in many other tribally organized societies that lack the institutions associated with the political state—law, police, courts, judges, and odious sanctions.”2

After all those years of wondering, I finally felt I understood something. So this is what the Arabs are afraid of? A society where the natural jealousy between men causes such a degree of division that any trace of civilization becomes impossible.

For example, in the anthropological book Guests of the Sheikh (1965) by Elizabeth Warnock Fernea, I learned that in rural Iraq in the 1950s, men didn't even talk about women. They said “my family” instead of “my wife”.3 Without knowing about the struggles of simple societies, I would have found such behavior completely illogical. But with the simple society of the Yanomamö in mind, I could make an educated guess: The men didn't talk about women because they were intensely jealous. Not talking about those precious creatures that everybody wanted was a way to avoid arguing over them. Which was a way to avoid becoming mortal enemies, like the Yanomamö inevitably did when their groups reached more than a couple of hundred people or so.

If women who no one owns are the foremost reason behind strife between men, making sure that all women are always, at every moment, protected by a man is a way to avoid that strife. Middle Eastern societies have gone all-in for that solution. I think the Saudi guardianship system, in which all women are under the control of some man, builds on that simple principle too.

One of the strangest thing I experienced in Syria was the pride people expressed and radiated. What I saw was a Third World country built on superstition and irrationality. And its inhabitants seemed genuinely proud of it. In general, they found it completely natural that I wanted to learn their language and know more about their great civilization. Very few people seemed to see the West as an ideal to emulate.

Now I think I can see clearer what they were proud of: They were holding chaos at bay. If you remove the idea that men possess a great degree of sexual self control, both problems and solutions become very different. The Syrians, just like the Yanomamö, were living in a world where male sexuality was an omnipresent, strong and disruptive force. The difference was that the Syrians had a system for controlling it, while the Yanomamö were fighting incessantly over it.

What justice?

From a Western perspective, the lack of a sense of justice is one of the most disturbing aspects of honor culture. For example, how can they kill women they themselves know are victims of rape?

Reading about the Yanomamö helped me also on that point. Anthropologist Kenneth Good reports that he once intervened when two men were pulling a woman in between them. The woman cried that she didn't care who took her if just any of them did. A middle aged man got tired of the quarreling and said “This is really annoying. I'm going to stab her, that will put a stop to it.” Then he went up toward the two contestants and the woman with a bunch of arrows in his hand. At that moment, Kenneth Good's Western sense of righteousness arose and he yelled “Don't do that”, and the man turned back.4 (Very annoyingly, Kenneth Good doesn't tell what happened then. We don't get to know how the dispute ended and who got the woman in the end.)

In a world without the concept of justice, stabbing the woman kind of made sense. Stabbing either of the men would probably have been far too dangerous for the squabble-tired man, so there was some kind of logic behind the thought of stabbing the woman instead and thereby removing the reason for the quarrel.

Yanomamö men could abuse their wives horribly, apparently in order to appear fearsome in the eyes of other men. There were no laws or even norms that prevented them from doing that. Whoever controlled a woman could do what he felt like doing with her, as long as no particular individual considered her worth defending. For that reason Yanomamö girls were afraid of being married into a village where they had no brothers who could defend them.5

There seemingly was little order in the way Yanomamö men abused the women they controlled. Jealous husbands regularly attacked wives they suspected of infidelity: They shot them with arrows, cut them with machetes and burned them with glowing firewood. About 5 percent of women died at the hands of men, most often their husbands.6

The Yanomamö did not regard women highly. Especially young women. They were seen as emotional and shortsighted. And still, women were the most valuable thing they could own. They were at the same time in low regard and considered endlessly desirable.

Fast forward

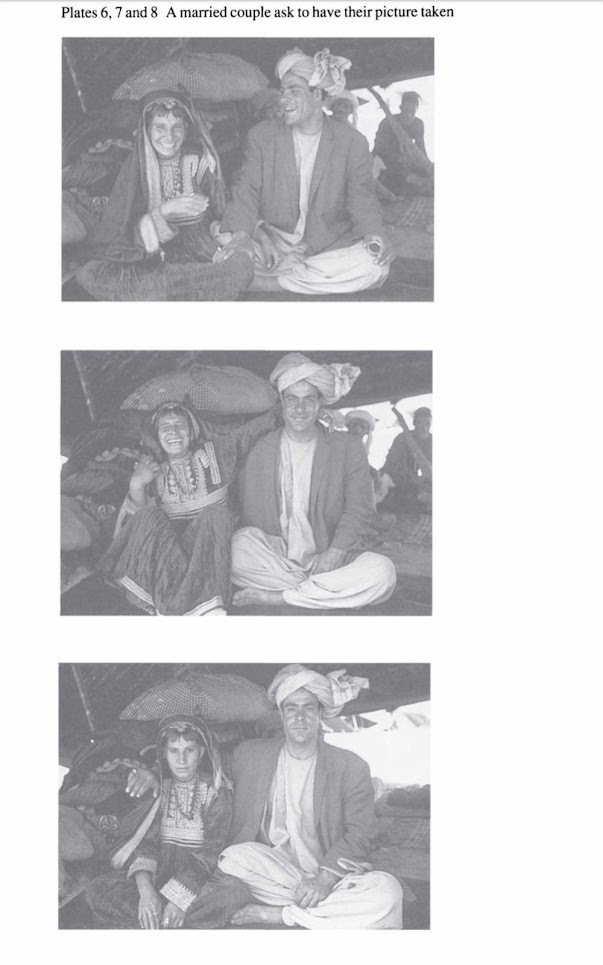

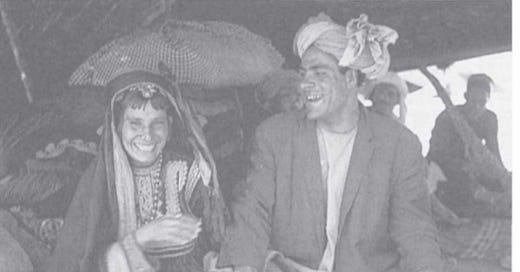

A couple of months ago I was recommended a book called Bartered Brides by Nancy Tapper (currently Nancy Lindisfarne). Bartered Brides (1991) is about a Pashto-speaking sub-tribe called the Maduzai in Afghanistan in the 1970s. Like many anthropology books, it is annoyingly badly written. But I read it anyway. Years of interviews with all kinds of members of a tribe of northern Afghanistan are difficult to resist.

As I forced myself through the pages, the Maduzai took shape as a scaled-up, a bit muted version of the Yanomamö. Yanomamö society was kept small-scale because of perpetual strife, in particular over women. The society in which the Maduzai lived and worked was significantly larger: The Maduzai sub-tribe consisted of 272 households (consisting of about 1900 individuals) and they were part of the larger endogamous Durrani tribe, which consisted of about 2500 households in the region.

Basically, the Maduzai Pashtuns live in the same lawless world as the Yanomamö. Just as the Yanomamö men, the Maduzai men had to organize their own military defense and uphold their own reputations as potentially violent in order to attain and keep women. Men perceived as weak were taken advantage of. They were tricked of their land-holding rights and had to give up their daughters to substandard prices.

Among the Yanomamö, the militarily stronger extorted the militarily weaker for women. The same thing happened among the Maduzai: Stronger, richer households tricked and extorted weaker and poorer households of women. But the Maduzai had adopted some codes of honor that allowed them to organize in much larger groups than the Yanomamö. Just like among the Yanomamö, or among modern Westerners, for that matter, there was an important degree of competition between households. But there was also a sense of ethnic identity. The Durrani never sold a woman to any other group (except to the Sayyids, a small group in the area considered to be descendants of the prophet Muhammed). They had Islam as a set of principles to broker peace between quarreling lineages. They owned livestock, land and money that was used to buy and sell women. They also had a codex for how to deal with expressions of women's own will.

From a Western perspective, Maduzai society was more or less as unequal, brutish and unfair as Yanomamö society. But it was less arbitrary. What among the Yanomamö seemed just as individuals getting one idea or another, was more elaborately codified among the Maduzai. The Yanomamö were jealous and tried to scare their wives into fidelity. But they had no detectable code for how and when it was appropriate to do so. The Maduzai had codified how to scare women from sexual independence to the degree that brutal violence against women was not just allowed, but semi-compulsory in certain situations. The Yanomamö could shoot a wife they suspected of something they disliked with a barbed arrow. The Maduzai had a system for when equal or worse acts of violence should be performed.

That being said, the system wasn't simple. Yanomamö men with weak potential for violence had to accept that fiercer men seduced their wives and took possession of their sisters and daughters giving little or nothing in return. Maduzai men with little influence were in the same position. The rule that straying women should be killed only applied to those who could afford it. Killing a female family member in order to uphold the image of being powerful was only meaningful for men who were powerful. Weaker men were seen as fools if they killed a daughter or sister instead of just collecting the brideprice they badly needed. Nancy Tapper writes:

“The value of a woman's life depends on the circumstances of the household in which she lives. For example, one local man was said to have murdered his daughter when she refused to agree to an engagement he had planned for her and sought to 'call out' for another youth: her father killed her before the lover could react (assuming he had intended to do so). In this case, though the father's drastic action conformed with ideals of honourable behaviour, other Durrani considered the man a fool who was too poor to afford such a gesture: he had lost his daughter and her brideprice and had gained precious little in return.”7

Also, men needed a wife for the survival of their children and the function of the household.8 Killing the mother of one's children was deeply unwise unless one was rich enough to replace her.

That way, honor killings were a kind of conspicuous consumption. A man killing a female family member showed that he could afford to instill terror in his female family members. Like all conspicuous consumption, it was only impressive as long as it was affordable. That way, females of lower social standing had considerable degrees of freedom. If they chose to elope with higher-status men, there was little their families could do about it, since the higher-status men could defend their brides. There was even a formal system for it: A woman could publicly call out for a man. Before doing so, she needed to assess the strength of her own family in relation to the man she wished to belong to. If he wasn't stronger than her family, her family members would swiftly kill her to maintain their image of strength.

In general, men had incentives to keep affairs secret. A Pashtun man informed another anthropologist, Bernt Glatzer:

“We know that a man guards his woman so that she cannot commit adultery, or he kills the adulterers. But who can always be standing behind his wife? Who wants to bring on himself the enmity and the vendetta with the family of the killed lover of his wife, and who wants to lose the brideprice which he had paid for his faithless wife? That is why most men keep their wife' s adultery secret. A shame which nobody talks about is no shame (Glatzer 1977:158).9

All-in-all, about ten percent of the women that Nancy Tapper surveyed had had premarital or extramarital affairs. None of them had been killed.10 They, if anyone, knew how to assess risk and opportunity in a dangerous environment. Sometimes females made a miscalculation, like the murdered girl mentioned above. But mostly they didn't.

A case of treason

One Maduzai girl who took a calculated risk in the early 1970s was called Kaftar. At the age of 17, she eloped with a Hazar servant. Her actions seemed deliberate: She escaped in the middle of the night and stole money from her father to take with her.

Great effort was spent in order to catch Kaftar. The plan was to shoot her in front of the women of the sub-tribe. A government official was bribed. The efforts went on for a couple of years, but they failed, mostly because the Hazara raised enormous amounts of money to outbribe the Maduzai among government officials. Kaftar remained with the Hazara to which she had escaped.

The household Kaftar escaped from was rich but troubled. A few years earlier her sister had an extramarital child with the son of her father's half-brother. The child was born in Mazar-i-Sharif and killed. Nancy Tapper writes:

“When people heard what had happened, they scorned Toryaley as soft - he should have killed his daughter first. This episode was the beginning of a series of violent quarrels between Toryaley and his half-brother which culminated in Kaftar's elopement. Some people said, perhaps correctly, that it was her [father's brother's son] who encouraged Sipahi to elope with Kaftar in the first place. With hindsight, they suggested that Kaftar would never have run away if her father had made an example of her sister, and some added that the whole affair would have been forgotten if it had been Kaftar's sister who had eloped.

However, if one tries to consider the elopement from what might have been Kaftar's point of view, it may indeed be the case that her father was the cause of her disloyalty to her household and decision to run away. It seems that when an unmarried woman 'calls out' for a man it is because she utterly despairs of her guardian's ability or willingness to arrange a reasonable marriage for her. I suspect that Kaftar may well have felt trapped in this way.

At the time of her elopement her father had been involved for many years in a very bitter quarrel with his half-brother and other close relations, which had been very costly and shaming. Certainly by the spring of 1971, well before Kaftar's elopement, people had come to despise Toryaley as a persistent troublemaker to be avoided at all costs. By this time, it must have been quite clear to Kaftar that, because of her father's reputation, no attractive suitor would ever come forward to marry her, and that her prospects could only get worse: she was already 'old' (perhaps sixteen or seventeen) and her contemporaries were now married women with young families.”11

Why didn't Kaftar do what so many other girls did in her situation and just accept her bad lot in life? We will never know what kind of personality she had, because, as is so often the case with criminals, people refuse to see the person behind the crime. People couldn't even remember how she looked.

“After she had eloped, her shame was conceived in such a way that it completely distorted the memory of her physical appearance, and she was often described to us as if she were a monster or a freak: with a blackened face, a crooked mouth and speckled, shifty eyes.12

Clearly, Kaftar's deed was something truly monstrous. What was her crime, then? It was treason.13 The bonds between Durrani households were fragile. A single act of violence could start a vendetta between families. They had few things bringing them together against other tribes and peoples. One of the few things they had was their sense of superiority. Through refusing to give women to other tribes, they kept a line between them and their own tribe. They were indeed competitive and even murderous among themselves. But they also had things that brought them together against other groups like the Hazara.

Through her behavior, Kaftar disregarded the fragile unity of her people. She would rather live decently among the Hazara than poorly and lonely among the Maduzai. For that reason, she was considered a demonic traitor by her co-tribesmen. A demonic traitor they were prepared to pay to see killed.

The botched attempts to bring back and kill Kaftar left Toryaley ruined. He was said to have mortgaged all his land. From his perspective, it seems to have been worth it. If he lost his reputation, he would be an open target for abuse. Toryaley needed to defend his reputation. Both his reputation as a strong man with capacity for violence and his reputation as a worthy ally in the Pashto alliance against lesser ethnic groups.

The East-West divide

Comparing the Yanomamö and the Maduzai, the Maduzai seem much like a polished and codified version of the Yanomamö. Both societies were doing realpolitik in their struggles over women and resources, just on different levels of sophistication.

The question is why all societies do not codify death penalties against sexual misconduct on the female side. If it is a logical continuation of men's attempts to control women, why does it then appear more or less exclusively in the Middle East and Central Asia?

All societies before the 20th century oppressed women. But only a few recommended death sentences for sexual misconduct. Classical Athens had quite a few things in common with Middle Eastern tribal societies: Women married early, they were secluded in their homes and in general held in low regard. But the accepted punishments for infidelity were less brutal sanctions like divorce and exclusion from public religious ceremonies. Not calculated murder.14

The reason why brutality against women took hold in the Middle East might be very old traditions. In The Horse, The Wheel and Language, archeologist David Anthony established that there seems to have been an East-Western divide in gender relations already among the Indo-European.

“Western Indo-European religious and ritual practices were female-inclusive, and western Yamnaya people shared a border with the female-figurine–making Tripolye culture: eastern Indo-European rituals and gods, however, were more male-centered, and eastern Yamnaya people shared borders with northern and eastern foragers who did not make female figurines. In western Indo-European branches the spirit of the domestic hearth was female (Hestia, the Vestal Virgins), and in Indo–Iranian it was male (Agni). Western Indo-European mythologies included strong female deities such as Queen Magb and the Valkyries, whereas in Indo-Iranian the furies of war were male Maruts. Eastern Yamnaya graves on the Volga contained a higher percentage (80%) of males than any other Yamnaya region.”15

That way, there might have been different groups with different traditions that migrated westwards and eastwards.

In general, there are excellent reasons not to kill one's own female family members. Both in a social sense and in an evolutionary sense. There is an evolutionary logic in treating wives and sisters and daughters brutally. But there also is an evolutionary logic in finding more gentle means of oppression. Some cultures developed ideals saying that even though men have power over the life and death of women, they should not use it. Other cultures instead developed ideals of how men should use their power of life and death over female family members.

Still among us

At a certain development stage, honor culture is a human universal. It is what happens when people need to manage their own defense, either as individuals or in family units. The honor culture among the Maduzai was much more collectivized and formalized compared to among the Yanomamö. For Yanomamö men, it was an ideal to be fierce. Men who were individually unafraid and selectively violent could gain big advantages for themselves and subsequently for their sons. Napoleon Chagnon mentions one example:

“Although Rerebawä displayed his ferocity in many ways, one incident in particular illustrates what his character can be like. Before he left his own village to take his new wife in Bisaasi-teri, he had an affair with the wife of an older brother. When it was discovered, his brother attacked him with a club. Rerebawä responded furiously: He grabbed an ax and drew his brother out of the village after soundly beating him with the blunt side of the single-bit ax. His brother was so intimidated by the trashing and promise of more to come that he did not return to the village for several days. I visited this village with Kaobawä shortly after this event had taken place; Rerebawä was with me as my guide. He made it a point to introduce me to this man. He approached his hammock, grabbed him by the wrist, and dragged him out on the ground. ‘This is the brother whose wife I screwed when he wasn't around!’ A deadly insult, one that would usually provoke a bloody club fight among more valiant Yanomamö. The man did nothing. He slunk sheepishly back into his hammock, shamed, but relieved to have Rerebawä release his grip.”16

This kind of behavior would clearly not have made any man successful among the Maduzai. For them, it was an ideal to be far-sighted, have judgment and to not get oneself hastily into conflict with kin. They found pride in being more deliberated than people of surrounding ethnicities, which were said to react too hastily and thoughtlessly.17 The Maduzai simply fought less as individuals and more on the clan level. In such a larger-scale honor culture, ability to cooperate within the family unit was what counted.

The more of a specialized military and police force a society manages to build, the less individuals and families are rewarded for upholding an image of potential for violence. Instead they are being rewarded for appearing to be loyal to society as a whole, for being good citizens. Is that the end of honor culture?

In terms of violence, yes. In mainstream Western culture it is no longer honorable to be seen as potentially violent. But we still have to fend for ourselves in a number of other areas in life, most notably professional success and social relationships of all kinds. Reputation is as important to us as it is to the Yamomamö or the Maduzai. But since our society is more complex, building a good reputation is also much more complex process. So complex that we prefer the less absolute expression social status instead: While honor is something rather simple that is decided by just a few very important parameters, social status is a sliding scale that comprises more or less everything.

In that sense honor culture never died. It only evolved. The notion of good people and bad people is very much alive in modern Western societies. We mostly don’t call them honorable and dishonorable. Instead, we put them all on a complex scale. And that is a subject that deserves a post of its own. To be continued.

Napoleon Chagnon, Noble Savages, 2013, 58 percent of e-book

Napoleon Chagnon, Noble Savages, 2013, 61 percent of e-book

Elizabeth Warnock Fernea, Guests of the Sheik: An Ethnography of an Iraqi Village, 1965, 8 percent of e-book

Kenneth Good, Into the Heart, 1996, page 71

Napoleon Chagnon, Yanomamö, 1992, page 125

Napoleon Chagnon, Noble Savages, 2013, 42 percent of e-book

Nancy Tapper, Bartered Brides, 1991, 67 percent of e-book

Nancy Tapper, Bartered Brides, 1991, 57 percent of e-book

Nancy Tapper, Bartered Brides, 1991, 63 percent of e-book

Nancy Tapper, Bartered Brides, 1991, 68 percent of e-book

That was Nancy Tapper's own interpretation of theKaftar case Bartered Brides, 1991, 67 percent of e-book

Nancy Tapper, Bartered Brides, 1991, 67 percent of e-book

That was Nancy Tapper's own interpretation of the Kaftar case: “her own betrayal of Durrani identity puts her beyond the pale and deserving of death” (Nancy Tapper, Bartered Brides, 1991, 68 percent of e-book)

Wikipedia on adultery in ancient Greece https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adultery_in_Classical_Athens

David Anthony, The Horse, The Weel and Language, 2007, 53 percent of e-book

Napoleon Chagnon, Yanomamö, 1992, page 30

Nancy Tapper, Bartered Brides, 1991, 63 percent of e-book

I really enjoy your writing and am very glad I found your work.

It’s rare that I comment on Substack, but I lived in the Middle East, speak some Arabic, and have many friends from the region (especially the Gulf), so I thought it might be useful to chip in (I apologize if it’s redundant).

Many of the things you describe are certainly real and terrible. However, I think there is definitely some sampling bias here. The mere fact that you were alone with a man is partly a taboo break. I can’t cite any statistics (I doubt any real study has been done to try and quantify this), but a non-trivial portion of the male population in these societies would deliberately avoid being alone with a woman precisely because it is understood as sexual and inappropriate.

Hence, those men who didn’t sort themselves out of being one-on-one with you (even if it was just the two of you walking down the street, not necessarily alone in a room) would have been those who were already open to being in a culturally sexual context with you.

This is of course a direct result of exactly the norms you mention, but I think it’s important to note that many Arab men are not just latently waiting to sexually harass women (and that’s expressed by avoiding solo interaction).

It seems to me that at its root, “guardianship” is partly a response to a lack of state capacity (as you’ve alluded to). Women are vulnerable to attack by men. If there is a centralized state with a reliable police force, some deterrence is established. In its absence, one way to protect them is for a family to require that they be with a male guardian.

Of course, it is obviously not all benevolent. Guardianship is also a way for a family to ensure that a woman pairs with a mate they approve of, regardless of her interests. The honor killing is a family’s attempt to enforce that power, as (again) without a centralized state, it is more necessary to enforce social norms (desirable or otherwise) directly.

In the case of rape, the problem here is that under such norms, it is expected that a woman avoid any setting in which they are alone with a non-mahram man. Consequently, not doing so is taken a sign that she is potentially sexually interested.

This is also why there may have been some sampling bias in your case. You were engaging in what would in the West be perfectly normal behavior, but signals something different under these norms. Even sitting in the front rather than the back of a taxi as a woman alone may send the wrong message.

Because of this, the family may blame the woman for her breach of honor (even though she did not consent to the sex itself), because they may perceive her as being at fault for “attracting the wrong kind of attention.” That is, by not more scrupulously restricting herself to the company of mahram men. The idea that wearing “immodest” clothing invites harassment is related to this.

Great analysis. A few thoughts:

1. From what I heard (I don't have any sources, it's just a stereotype), arabic men treat western women entirely differently than arabic women, so you cannot infer a general theory of how arabic men treat women based on how they treated you. Then again, maybe the difference was that for them, a western woman is like the woman with no father or brothers to look out for her in the Yanomamo tribe, and this is why they have no problem with groping her.

2. Linking sexual self control with things like 'honor' and 'self respect' in western cultures has in some cases gone to far and resulted in men struggling with women and becoming incels. This is something the pickup artists tried to counteract (FYI I covered it in my recent post here: https://transhumanista4all.substack.com/p/confessions-of-a-pickup-artist-pt )

3. Your mention of the Yanomamo and Maduzai beating and hurting their women reminds me a lot of Rob Henderson's recent note about chimpanzees beating their females: https://substack.com/@robkhenderson/note/c-57975912 . This sort of explains where all of this violence originates from. Advances in anthropology make it seem like we are actually very close to our closest animal cousins.