Is child murder the cause of greater female linguistic ability?

Showing off is the main purpose of unusually high linguistic ability. During human history, males and females needed to show off at very different ages

Evolution happens through both sexes. But it sometimes happens a bit differently among males and females. In primitive societies, mortality patterns tend to differ among males and females. In general, primitive societies that make war can't afford to raise as many females as males, because only the males will become warriors. For that reason, more females than males are killed as newborns or killed or neglected during childhood. Males instead start dying en masse when they reach their teens and early 20s and start participating in warfare. Females who have reached that age survive a lot better until old age. They also reproduce at rather similar rates, since their high mortality during childhood makes survivors scarce enough to all reproduce to their maximum.

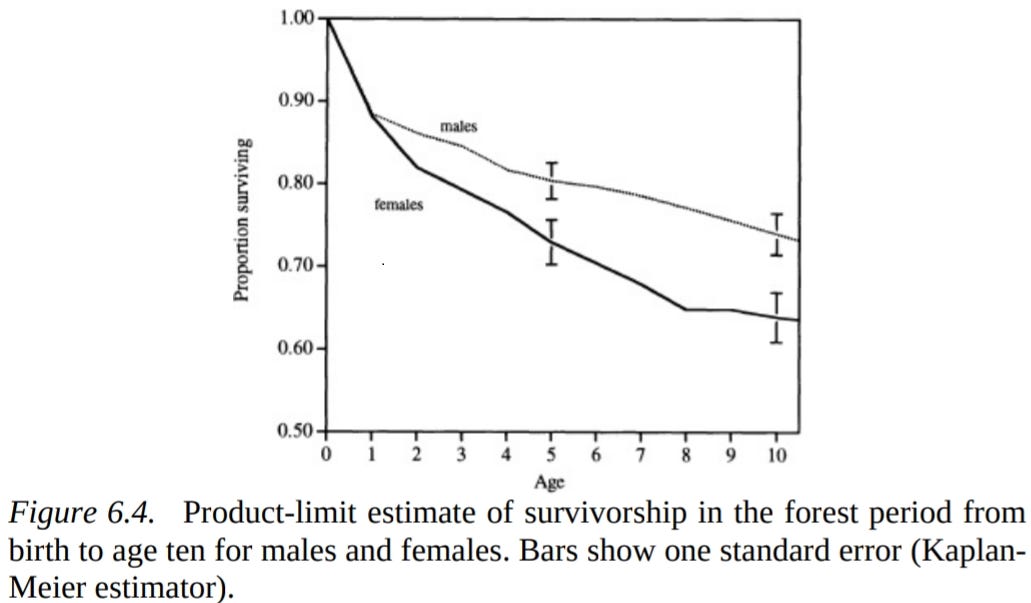

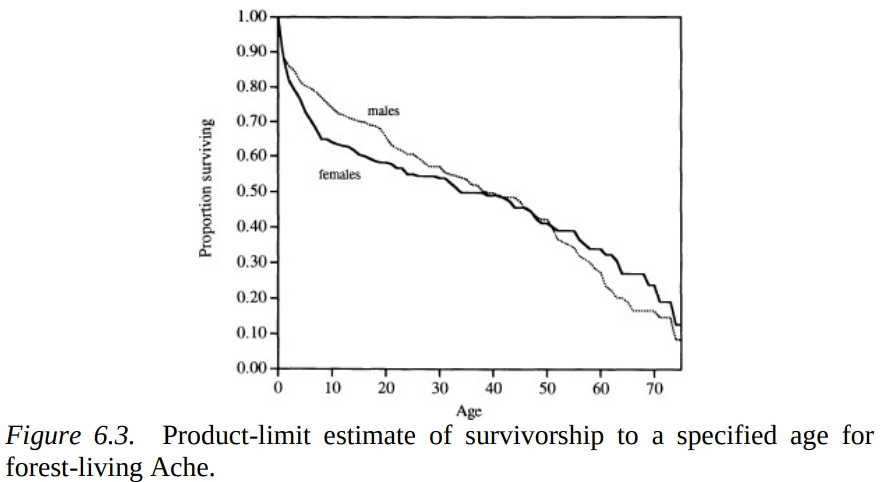

Above is a graph from Aché Life History (1996) by Kim Hill and Magdalena Hurtado, showing survival rates at different ages for Aché males and females from the time when they lived as hunter-gatherers. Females are much more in danger during their first years of life. Then males start dying at higher rates in their late teens. Around age 40, the number of females exceeds the number of males due to the high mortality of males in their prime.

The Aché is only one meticulously studied hunter-gatherer population. But their male-female mortality pattern has been recorded numerous times among primitive societies at war. In the 1970s anthropologist William Divale compiled data from hundreds of primitive societies. Among 160 societies that still practiced warfare, the average sex ratio was 128 boys for 100 girls under 15. Among the populations that had stopped warfare at least 26 years prior to the census, the male-female ratio for under 15s was 106 boys for every 100 girls.1 That is, about the same rate as in modern European and Asian and Native American populations (in modern African populations the sex ratio at birth tends to be 103 boys for 100 girls).

Given the growing evidence of humanity's violent past, those findings hold very important implications for evolutionary psychology. If females tended to die without reproducing at one age, while males died (before or after reproducing) at another age, that means that males and females faced different evolutionary pressures throughout life. Not only did males and females meet different challenges at the same age. Different developmental stages were also of different evolutionary importance.

No selection at all?

In some societies, an important portion of excess female mortality occurs at birth. Infanticide is widely practiced and girls are killed at disproportionate rates.

The females who are left to live then become scarce and sought-after. Men can't afford to pick among them - every fertile female is a good one. The lack of females, often coupled with polygyny, means that all females who are not outrightly malformed will have children, while all men won't. That means that for females, an important selection event, maybe the most important of them all, occurs at birth. For males, selection occurs at higher rates at adult ages: The sport is to secure a female or two without getting killed in the process.

Being selected at birth is close to being selected at random. It is very difficult to see the eventual qualities of a newborn infant. That means that as long as the whole deficit of females can be explained by female infanticide, there is in practice little selection on the female side.

Dangerous years

But there is no reason to assume that infanticide lies behind all of the high mortality among little girls. Most of the Aché girls who died from violence before age 15 were not killed as newborns. Instead, most of them were murdered at some occasion before they turned 5.2

The Aché lived as hunter-gatherers until the 1970s. Until then they were not pacified by civilized society. Their mortality rate from violence was very high. Over 40 percent of adult deaths were caused by violence by other Aché or outsiders.3

But even more child deaths were caused by violence, around 60 percent of the total. About 23 percent of girls and 14 percent of boys were sacrificed at the funerals of dead adults, most often males. The Aché said that the dead man profited from some company into the next life. A child, most commonly a small girl, was led into the grave and buried alive.4

However, the ritual sacrifice aspect mostly seems to have been a pretext to get rid of unwanted children, because a child was only sacrificed when there was a child that no one agreed to take care of. If anyone dragged the child back from the grave and volunteered to take care of the child, the deceased man had to make it without company in his grave. Most of all, orphans were sacrificed, because people abhorred them for their constant begging. But every child without staunch protectors was in danger. Anthropologists Kim Hill and Magdalena Hurtado, who collected Aché people's memories of the forest period, report that several informers recalled being dragged to the graveside when their father had died and saved by a relative.5

Was this normal behavior?

I have only read about such a gruesome custom once. In his attempts to explain the gender gap between boys and girls in his above-mentioned compilation of censuses of primitive societies, anthropologist William Divale mentions no similar act of open cruelty. But he doubts that all the excess mortality among girls happens at the newborn stage. He writes:

"Nonetheless, preferential overt female infanticide must be reckoned as only the tip of the iceberg. Many cultures with markedly skewed junior age-sex ratios deny that they practice any infanticide at all. Hence it can be inferred that the sexual imbalance in favor of males is achieved as much through covert infanticide, including clandestine aggression and various forms of malign and/or benign neglect that adversely affect the survivability of female infants".6

In other words, the particularity in the Aché way to get rid of unwanted children of the wrong sex might most of all have lied in its overtness. Somehow, people in primitive societies that wage wars have found ways to make more boys and girls survive childhood.

Also from recent and rather civilized and peaceful societies, there are strong indicators of selective neglect of girls. India is the school example. Some Indian agricultural societies infamously practiced infanticide into the 20th century. But they also disproportionately neglected girls through giving them less nutritious food and monitoring them less carefully7. Mortality rates have been found to be specifically high among girls with two or more older sisters.8 A recent study of child mortality data from 195 countries found that all over the world, the death rate of girls compared to boys tends to be higher in societies holding less gender-equal norms.9

Cruel logic

When the Aché killed children at the event of the death of a man, commonly their father, they streamlined their numbers of dependents to fit the number of providers. Contrary to most modern hunter-gatherers, the Aché were heavily dependent on adult males for food acquisition. Kim Hill and Magdalena Hurtado estimated that most calories were obtained by men's hunting (when Hill and Hurtado followed Aché bands into the jungle, men obtained 87 percent of calories, mostly from meat)10. That makes them more similar to the Inuits than to other hunter-gatherers of temperate areas, like the Hadza of Tanzania or the Australian Aborigines, where women were the main providers.

If the Aché had attempted to kill those excess dependents off at birth, they wouldn't have known exactly how many to kill and how many to let live. The group's capacity to raise children depended on the number of providers. And the number of providers varied in an unpredictable way. Although publicly murdering children at conscious ages is an obviously cruel custom, it probably gave the group a certain advantage in numbers: It could always keep its number of dependents at a maximum. The same is true on the family level. Families could raise as many children as they would have raised if no adult male died, until an adult male actually died.

Selectively neglecting children so some of them die has the same effect as brutally murdering children when the food supply decreases: It streamlines the number of dependents to the supply of food and adult attention. Instead of murdering unwanted children, they are given less food and attention and more of them will die. The mechanism is the same, although less clear: Raise the maximum number of children. When food and attention gets scarce, sacrifice the least wanted. Not all of them will die. Not all of the most wanted will survive. But the more wanted children will survive more than the less wanted children.

Let the best girl win…

Both childhood murder and childhood neglect disproportionately hit against girls. Which means that in evolutionary terms, females are more selected at young ages compared to males.

The evolutionary implications of this are vast, and largely overlooked. Evolutionary psychologists commonly look at males and females of the same ages and try to figure out how they both were selected after their particular circumstances. But what if females were actually more selected as girls than as women? Then it makes sense to look at the living conditions of females as children and males as adults, in order to understand the formation of some sex-specific traits.

The girls killed by the Aché were not randomly selected. Girls who were well-liked enough to be saved by some relative weren't killed. The relatives subjectively decided whether saving a girl was worth it or not. It is the same with the neglected excess daughters of agricultural societies. Their parents choose to neglect them. They can choose to prioritize differently, if they find the girls adorable enough.

Childhood has always been a charm competition. But it seems to have been so more for girls than boys. Girls commonly constituted a buffer population that should be raised if there were enough resources, but that were neglected or killed when resources became scarcer. That way, competition among little girls was fierce. Not on a conscious level, but there certainly was a selection process where the children who appealed the most to caretakers were selected for. And that process most probably was more intense on the female side.

Learn to talk!

What could a girl do to get a fair chance of growing up, despite there being too many little girls applying for a place in life?

To be promising and precocious is one safe bet. There is a theory that human linguistic ability rose as a consequence of competition between children. Humans are far from the most K-selected species on Earth. Our cousins the great apes get fewer children. That means that human children need to compete more with each other than ape children. The theory goes that the children with the highest linguistic ability were selected over the children who could only scream and grunt at certain ages.11

If children were selected for their linguistic ability and girls were selected more than boys, that should imply that girls were disproportionately selected for early linguistic ability. According to a number of studies, adult women have a slight linguistic advantage compared to adult men (other studies show no such female advantage). One and a half year old girls have a significant advantage over boys the same age. For example, 70 percent of all early talkers are reported to be girls and only 30 percent are boys.12 Adult women are not even close to that level of linguistic superiority over adult men.

The early female advantage is either explained as an aspect of generally earlier female maturation or as a way for girls to develop into linguistically savvy women. But there is another possible explanation: Linguistic ability was selected for in young children. Young girls faced stronger selective pressures than young boys. The linguistic advantage among adult females could be a mere residue of the linguistic advantage among toddler girls.

Linguistic feathers

Over the years, I have stumbled over a couple of explanations of the slight gender gap in linguistic ability between the sexes. One is that it is an effect of females being the most social sex. Since females raised children, they needed to be able to talk to those children. Females also relied on gossip more than physical strength. They needed to talk to make up for their lack of physical prowess.

But seriously. How much verbal IQ is required for childcare? Few modern parents choose child carers on their high linguistic merits. For people who are taking care of children up to about seven years, as women commonly do in primitive societies, linguistic abilities higher than average are seldom seen as a selling point.

And also, are people with high linguistic abilities better gossipers? When I was a teenager, I spent a lot of time in a very gossip-rich environment called school. I have no memories of the more linguistically skilled people being better gossipers. A certain rate of social aggression seemed much more important than an unusual ability to use words and grammar.

Rather, higher-than-average linguistic ability is a means for showing off. It can be used to make speeches, sing songs and write poems that impress people. Which is something that adult males did much more than adult females in history. Public performers of every kind were disproportionately male. Calling together a war party with superior rhetoric was most probably a male task. Entertaining people was mostly a male task. High-level negotiation was mostly a male task.

Both males and females needed high linguistic ability in order to signal their prowess. They just needed to do so for very different reasons, at different times. And ultimately, the little girls might have needed it even more, since an unusual ability to talk was one of few weapons they had to improve their chances.

Kim Hill and Magdalena Hurtado, Ache Life History, 1996, 17 percent

Kim Hill and Magdalena Hurtado, Ache Life History, 1996, 17 percent

Ridhi Kashyap and Julia Behrman, Gender Discrimination and Excess Female Under-5 Mortality in India: A New Perspective Using Mixed-Sex Twins, 2020 Link

R.L. Bhat and Namita SharmaMissing Girls: Evidence from Some North Indian States, 2006 Link Sci-hub link

Anitha Raj, Nichole E John's and others, Associations Between Sex Composition of Older Siblings and Infant Mortality in India from 1992 to 2016, 2019 Link

Neelam Iqbal, Anna Gkiouleka, Adrienne Milner, Doreen Montag, Valentina Gallo, Girls’ hidden penalty: analysis of gender inequality in child mortality with data from 195 countries, 2018 Link

Article in The Conversation https://theconversation.com/more-girls-die-under-age-five-in-countries-with-high-gender-inequality-105911}

Kim Hill and Magdalena Hurtado, Ache Life History, 1996, 16 percent

I found this theory in a Swedish book on linguistics, Språken före historien (2019) by Tore Jansson

Yet another Wood From Eden post that makes me *extremely* grateful to be a 21st century human from a developed country. I feel like there is a trend among learned folk to harshly criticize modern cultural practices (late stage capitalism!) and for some to opine for a return to primitivism (degrowth?). I get the sense that those people have not studied what primitive, premodern life actually looks like, and therefore cannot appreciate what a magical thing "capitalism" is in its ability to break us free from basic scarcity, and of the vast scale of injustice and depravity that would occur otherwise.

Such commonality of ritual killing makes me think of the child murder scene from The Giver. The shock and revulsion that comes from realizing the nature of the crime taking place against another human. I wonder if the Ache and other infanticidal societies knew truly what death means, or if they subscribed heavily to some "true world theory" that made death a less than huge deal.

In general I feel always a bit iffy about human evolutionary claims based on studying more "modern" hunter gatherer tribes. I wonder if there weren't confounding selection or environmental pressures that led to the tribal peoples that we can find today (or in the 1980s) to take on particular societal forms that were less common during our bulk evolution, (the 200k years or so on the savannah/in east africa when we developed our more complex communication and cultural abilities). Do you have any thoughts on this? Do you think that it is fair to make inferences about the "evolutionary setup" for human evolution based on modern-day primitive tribes?

Very interesting post. I hadn't really considered these kinds of gender dynamics much before, but they do seem like they they probably were a major feature of primitive societies.

One question I have about this theory though is:

I can see why the tribe as a whole might want more males than female children. But since military protection is a public good (i.e. something that's provide by the group as a whole and benefits everyone in the group), and individual families benefit equally from having either male or female children in terms of reproductive success (expected fitness has to balance between males and females, right), isn't their a collective action problem? If a family has already invested resources raising a female child, they're not going to want to waste that investment even if it would be better for the tribe as a whole to invest the resources in male children.