Anorexia was the gender dysphoria of yesterday

Both socially induced psychological illness and ambivalence toward the female condition is much older than the gender dysphoria boom

Gender dysphoria has sailed up as the number one socially induced psychological disease of our time. About a decade ago, apparently out of nowhere, people started questioning their gender identity. Since gender dysphoria is fashionable here and now, it is talked about as something very particular. A book called Crazy Like Us: The Globalization of the American Psyche (2011) by journalist Ethan Watters suggests it isn't. Psychological disorders have always been sensitive to trends.

Watters presents the way Western-style anorexia reached Hong Kong as his main example. He interviews a psychiatrist called Sing Lee, who watched the whole process from the beginning. He also anticipated what would happen: That the thing that had sparked an epidemic of anorexia in the West, whatever it was, would sooner or later arrive in Hong Kong too.

Sing Lee trained in England in the early 1980s. As a part of his training, he learned about anorexia. When he returned to China and Hong Kong in the early 1980s and worked at a psychiatric hospital, he searched for cases in that part of the world. In the databases of the Prince of Wales Hospital in Hong Kong he could only find ten possible cases between 1983 and 1988.

Lee was puzzled by the difference. Traditional Chinese culture did indeed not fat-shame. Being rich enough to eat well was traditionally considered good fortune. Still, Hong Kong wasn't traditional China. Ethan Watters writes:

"But even taking these differences into account, Lee couldn’t quite understand why the behavior was so uncommon among local adolescents. In many ways Hong Kong seemed primed for the disorder. It was a modern region that, thanks to years of British rule, had incorporated many Western values as well as styles of dress and eating. There were fast-food restaurants and health clubs. Thin Western and Chinese celebrities were idolized. It was a patriarchal culture, in which parents and teachers put intense pressure on students to compete. The Chinese obsession with food and the layered meanings of sharing meals within a family should have made food refusal a dangerously attractive behavior for an adolescent looking to send a distress signal to those around her."1

In spite of that, the few cases of anorexia Sing Lee found to study were among lower-class women. The patient he came to follow the closest was a woman in her thirties who had been deserted by her boyfriend four years earlier. She didn't express any wish to be thin. Instead she talked about indigestion. After several years and several treatment attempts, she died of starvation.

Lee became interested in an American scholar called Edward Shorter, who had studied anorexia in the West throughout the 19th century. Shorter's early cases were similar to the cases Lee saw in Hong Kong in the 1980s: The patients tended to describe their refusal of food as physiological: They said they had stomach pain, lack of appetite, vomiting, or the sensation of having a lump in the throat. Towards the end of the 19th century, self-starvation became considered a more prominent component of hysteria, the trending female mental illness of the day. Subsequently, the prevalence of self-starvation rose.2

Lee became so curious of his anorexic patients that he decided to starve himself for experimental purposes. During the first three months, he only felt bad like any dieter. Then he entered some kind of euphoria:

"His energy began to return and his mood improved—more than improved, actually: he felt great. He was going to bed later and waking up earlier. He performed behaviors that he would have identified in a patient as potentially pathological. As he rode the elevator up to his office every morning, for instance, he did arm exercises on the handrails. He began to feel a hyperalertness and sense of mastery over his body and his life. For much of the day he was on the sort of pleasant runner’s high that one feels in the middle of a good workout. His hunger, which for months had been sounding a deafening alarm, had become a background whisper that he could easily ignore.

He found himself feeling somewhat superior to other people, who seemed to be ruled by their incessant need for food. He couldn’t understand why so many people who tried to diet lacked the willpower to do so. He found that he was inordinately pleased that he had the strength of will to see his project through. The next ten pounds came off with little effort and his friends and family began to comment on how thin he was. He had lost over 12 percent of his body weight.

Although Lee felt the desire to stay on his restrictive diet, he managed to shake himself out of the behavior. His excuse to himself at the time was that he needed to go to London for an intense exam at the Royal College of Psychiatry, and he worried that his lack of nutrition would limit his mental abilities. It had been a dangerous experiment but a successful one; he had heard a bit of the siren song that patients with anorexia often follow to their death.

One of his patients once told him that anorexia felt like getting on a train, only to discover too late that she was headed in the wrong direction. This patient felt she had little choice but to stay on that train to the final destination. Lee now had some idea what she meant when she used that metaphor to describe the psychological momentum that can build behind anorexia. He had starved himself to the point where the behavior can turn from a willful choice into a dangerous addiction."3

The big breakthrough

By the beginning of the 1990s, more psychiatrists in Hong Kong became aware of the Western perception of anorexia. Sing Lee observed how his colleagues tried to squeeze their patients into that pattern through giving them leading questions. But the mass media reported little about any such disease and the public was largely unaware of its existence.

That fact began to change on November 24, 1994. That day, 14-year-old Charlene Hsu Chi-Ying died on a busy shopping street in the middle of Hong Kong city. She weighed just 34 kilos by then. Charlene was emaciated when she died. Still, she didn't fit in very well with the Western concept of anorexia. She had never been heard saying that she was dieting or tried to lose weight. People around her had just noticed that her mood had deteriorated and she had become sullen.4

Charlene's very public death made big newspaper headings. Experts were asked for reasons behind Charlene's illness, and they introduced the public to the Western concept of anorexia. Schools were recommended to provide counseling on eating disorders and their consequences. Over a few years, teenagers in Hong Kong were made aware that anorexia was not just a disease for Westerners. They were taught that they themselves were also at risk of the disease.5

In the second half of the 1990s, the thing that Sing Lee had feared would come to happen did really happen: The number of anorexia patients exploded. In the hospital where Lee was once seeing two or three anorexic patients a year, he was now seeing that many new cases every week. Newspapers reported increases of the same magnitude, sparking new alarmist reports about the terrible disease that had now reached Hong Kong.6

Meanwhile in Europe

On a personal level I find Ethan Watters' story very credible. I was born just a few years later than Charlene, in the part of the world that held the origin of the Hong Kong mass media hype. In the 1990s, anorexia really was a big thing in the public mind. Newspapers published voyeuristic pictures of emaciated young girls. My school showed documentaries about teenage girls who had eating disorders and died from anorexia.

The awareness campaigns certainly reached me. My family members were vigilant. Especially my grandmother. She was alarmed by that terrible disease and told stories she had heard on the news to her granddaughters. I did my best to educate myself too. There were two novels featuring girls with anorexia in the local library. I read both as a preteen.

I remember the exact moment when I turned that knowledge into an eating disorder. I was 13 and a half years old. The summer holiday had just started. I had nothing planned for the whole summer. I stood in the kitchen and thought: "I'm going to develop an eating disorder. For real." Since I knew anorexia existed, I was free to get it whenever I decided to.

And I did. I read books about weight loss. I exercised ambitiously. I developed tricks to eat less without going crazy. Half a year later, I had lost 5.5 kilos. From 46 kilos on 160 centimeters to 40.5. That was enough to make me look emaciated and for my health to decline. To an important extent my experience was the same as that of Sing Lee: Although eating less was associated with being tired and ill, it also resulted in a special kind of energy. Hunger became a background feeling that was almost pleasant. Abandoning that constant feeling of hunger felt like a great loss. I got the strength to do it only from planning to start starving again as soon as I had reached a healthy weight. The process of putting on the lost kilos felt worse than losing them.

Most of all, I was surprised that starving was so easy. I searched for something to busy myself with and thought that having an eating disorder would do fairly well. I didn't imagine having to choose between recovery and a path towards death in just half a year.

Gender trouble

I recovered rather quickly from my state of starvation. After that short experience of malnourishment I knew to keep my eating disorder on the civilized side. No more starving towards really dangerous levels of malnutrition. Just an ongoing, on-and-off project of body modification.

I kept it going for four years, until I was 17. During those four years, I came to articulate a reason for my wish to be thin: I wanted to escape the curse of femininity.

I never got the idea that I wanted to be male instead of female. That idea was absurd. Girls grew up into women, boys grew up into men. Every sensible person knew that. But I imagined that I could grow up into a woman who was not that much of a woman. A soft, typically feminine body was indeed considered attractive by many men. But it was also vulnerable to their judgment. A soft version of me would be completely dependent on the male gaze. If men liked it, it would have a value. If they didn't, it would just be gross.

Now that food shortages aren't a thing anymore, the only point of fatty breasts, hips, buttocks and thighs is that they can be looked at and felt. It places females in a position of both power and dependence. For those few who have perfect, unassailable proportions, then power overrides vulnerability. In that case it could have been a good deal, I reasoned. But already in my early teens it stood clear to me that I wouldn't become one of those beauty queens. I saw that I would become just a woman among others. And then I preferred to be thin and muscular instead of femininely built. Like a robot, more or less: Bones, muscles, skin, head, face. Everything just functional. The less fat, the less for others to judge. Not much to like, but also not much to dislike.

Superfluous shapes

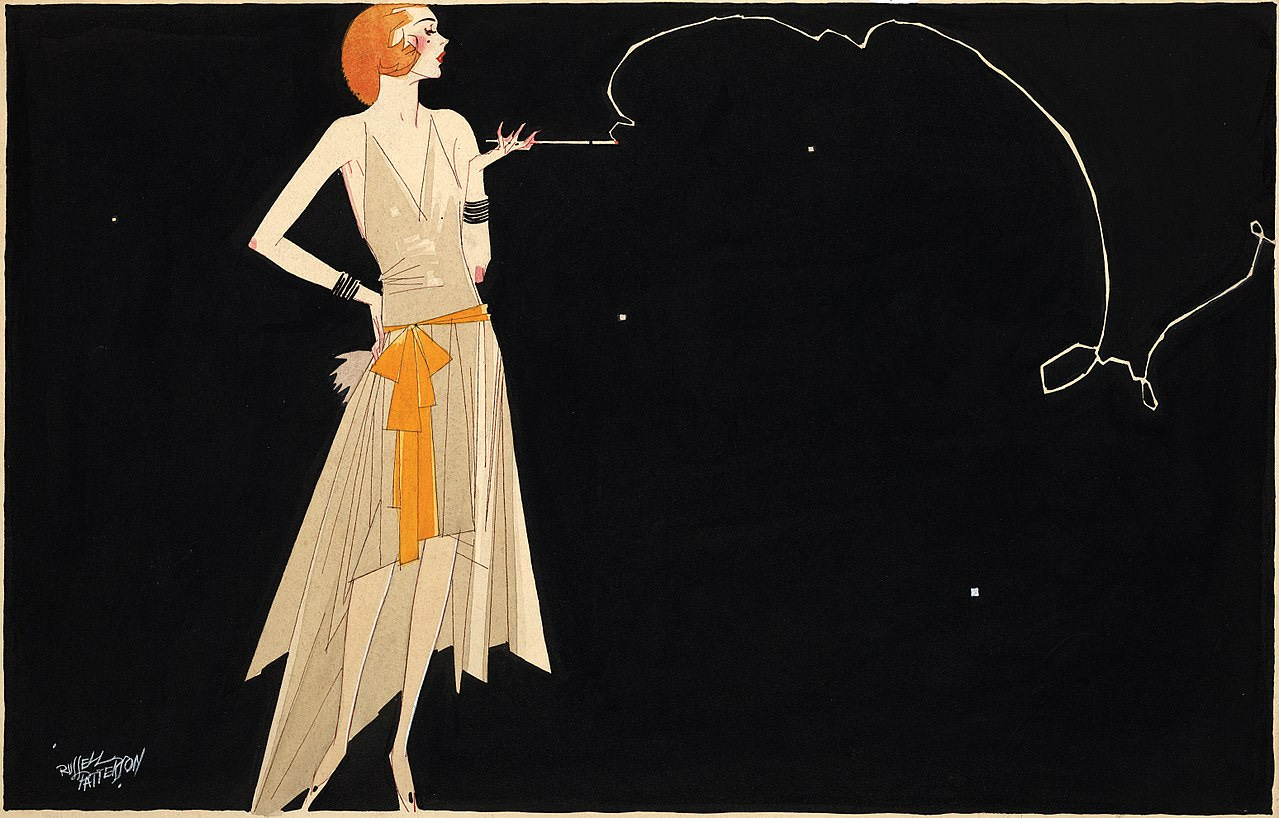

I can't have been alone in that feeling. Why did those thin beauty ideals rise in the first place? It wasn't the fault of men. That much I learned already as a teenager. One of those arguments repeated again and again was that men actually didn't prefer women to be that thin. Women who work with entertaining men tend to be normal weight. The unhealthily thin ideals are mostly created for a market of females. What's in it for them?

I think it is gender dysphoria light. Thinness represents female freedom and action. Thin women are also women. But not in the weighed-down, dependent way. Female thinness represents independent action, while maximal femininity represents dependence on males. It is no coincidence that ideals of unusual levels of thinness came to life at the same time as ideas of female liberation took root. A lack of body fat signals a certain independence from a traditional, sexuality-based female life. Thinness signals that a woman is up to other things than being a wife, a mother (or a whore).

Modern teenage girls are supposed to be such independent women for years after puberty. When they develop a voluptuous, feminine body shape, the change is supposed to be solely on the physical level: They are not supposed to use those recently acquired curves for anything. Not for having sex for years to come. Definitely not for having children.

That way, female puberty means getting a body that is, in many ways, less useful here and now than the bodies they had before. Girls need some imagination to find the bodies that will be appreciated by future lovers meaningful here and now. Some manage to do so, while others see just pointless layers of fat.

Anders and I once discussed what puberty means on the physical level, and he mentioned that on one occasion he was in gym class and discovered that he could climb a rope only with his arms, just out of nothing. That was such a contrast to my mixed impressions of my growing body as a teenager. While puberty was a simple win for him, it was a confusing mix of wins and losses for me.

My exit from eating disorders came exactly from the realization that the whole thing was about gender dysphoria. When I could spell out to myself that I was dieting in order to escape femininity, I saw the obvious contradiction: Is there anything more feminine than narcissistic, detailed body modification? If I wanted to be less feminine the solution must be to act less feminine, not to modify my body a bit more to the masculine side.

Just as I could think myself into an eating disorder at 13, I could think myself out of it at 17. After concluding that a fat-free body is not an escape route from the female condition, I have never seriously tried to lose weight again.

Don't speak

Although the prevalence of gender dysphoria has exploded among teenage girls, eating disorders have in no way disappeared. To the contrary: the prevalence of anorexia has been stable or rising along with other types self-destructive behavior.

Still, I have the impression that the same psychological type of person fell victim to both gender dysphoria and anorexia, at different times. A certain subset of the population is vulnerable to certain cultural triggers. First and foremost, autistic traits are very much associated with both anorexia and gender dysphoria.

When I wrote my one and only anti-trans post, I got one or two comments implying that I might lack empathy for people with gender dysphoria. I don't think I do, because I have suffered from body dysphoria myself, which cost both me and those around me a lot. I know from my own experience that an illness can be both very real and culturally induced at the same time.

If Ethan Watters is right that most psychiatric disorders are culturally induced, that implies that it should be a rule to be very careful about how to talk about psychiatric disorders, especially with children and teenagers. I follow that rule myself: I will not warn my kids about eating disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder and similar easy-to-self-induce problems before they clearly have them. Until then, I think it is better to just chill and say things like "I think you will feel better if you eat something" if they are experimenting with the latest dieting fad. If I say "Watch out so you don't get that terrible disease anorexia", I will have told them that eating patterns are a question of identity. Which they shouldn't be.

How to talk about psychology?

This question opens for a much bigger discussion: How can psychology help people as much as possible while doing as little damage as possible?

Ethan Watters' perspective in Crazy Like Us is that psychological disorders are real - and diffuse. A few people have largely biologically shaped disorders like schizophrenia, that manifest themselves rather similarly all over the world. Most people with psychological disorders just feel bad. Society has to tell them how to explain and express that feeling.

In every society, the people who feel that life is unbearable try to do something about it. Different societies give people who feel bad different explanations to their bad feelings and different opportunities of action. Some societies talk about bad spirits, Yin and Yang balances and or the Devil. Westerners 150 years ago talked about hysteria. Unhappy teenage girls of that time fainted, went kataplexic and, toward the end of the 19th century, developed anorexia nervosa. Whatever disorder is in fashion, people, especially teenage girls, will get it. With that knowledge, disorders should be designed with what we want people to get in mind.

Somehow, it seems like Western society is already doing that with its concept of depression: Depression is, essentially, bad feeling in itself, expressed in a calm and comparatively non-dangerous way both for the people around and for the victim themselves. Compared to hysteria, anorexia, and gender dysphoria, depression is easy to go in and out of. Despite some outliers who express their distress in conspicuous ways with irreversible consequences for themselves, most unhappy Westerners (and there are many of them!) are just as silent and as well-behaved as possible.

Everybody is special

But most of all, I think that paradoxically, the best thing psychology could do to help people is to focus less on helping people. When psychology is studying different expressions of feeling bad, it inevitably also creates manuals for what to do when one is feeling bad.

A long time ago I read a book on sexuality research, Bonk (2008) by Mary Roach. Researchers interviewed there spoke of their difficulties to get funding for their research on normal human functioning. Those holding the purse strings wanted research on dysfunctions, not research in the normal and functioning, because research on the dysfunctional is supposed to help people in distress.7

I think that kind of assumption is completely wrong. Especially in psychology and related sciences, normal human functioning is the thing to study. When people get dysfunctional, they are, in many cases, not sane enough to think anyway. The more people need psychology, the more susceptible they will be to whatever it suggests. The less psychology will be an observational science. The more psychology studies people in distress, the more it comes to live in symbiosis with those people. A symbiosis that is not healthy for any of the parties.

The more psychology instead focuses on functioning people, who actually don't need it, the more free it will be to observe. Instead of studying people in deep distress, it would be much more constructive for psychology to focus on people who feel rather well. Especially, it would be constructive to focus on different ways of feeling rather well. If tools for self-understanding aren't offered until people badly need them, they will come in a color of desperation. I'm crazy because… If being crazy is the only alternative to being entirely normal, people are almost pushed into craziness.

Psychology didn't emerge as a discipline different from philosophy until in the late 19th century. I think it would gain from taking one step toward philosophy again, and seek to answer questions like: What is it like to be a human? Instead of studying exceptions from some kind of perceived normalcy, I think it should focus on the human condition in all its complexity.

A plea for book tips: Since I am currently taking care of a baby, I would like to read more about how people have been taking care of infants in time and space. Especially in pre-industrial societies, but every non-Western population is of interest. I'm after any publication that tells who did what in order to assist the growth of an infant in as many corners of the world as possible. Please post a comment below if you know of any such books or articles.

Ethan Watters, Crazy Like Us: The Globalization of the American Psyche, 2011, 7 percent

Ethan Watters, Crazy Like Us: The Globalization of the American Psyche, 2011, 11 percent

Ethan Watters, Crazy Like Us: The Globalization of the American Psyche, 2011, 9 percent

Ethan Watters, Crazy Like Us: The Globalization of the American Psyche, 2011, 15 percent

Ethan Watters, Crazy Like Us: The Globalization of the American Psyche, 2011, 16 percent

Ethan Watters, Crazy Like Us: The Globalization of the American Psyche, 2011, 17 percent

Mary Roach, Bonk, 2008, 14 percent

Fascinating and cogent, as usual. I'm left wondering about male gender dysphoria, because there seem to lots of boys who want to be girls these days. Is this also a newly acceptable way to express unhappiness with their gender condition - in this case maleness? And if so, what were the disorders that preceded it, as anorexia preceded female gender dysphoria?

Good article. I have thought about this trend as well. the connection seems clear to those of us paying attention. A big difference from the medical community at least in the United State is how anorexia is treated vs. gender dysphoria. One of them being treated to reverse the disease with therapies, counseling, nutrition consults, and feeding tubes in severe cases, while the other is treated with affirming care. Imagine taking that approach with anorexia, i.e. a gastric bypass to treated an anorexic's desire for weight loss.