Up where we belong

A book review

This article was written as a book review for the Astral Codex Ten book review contest already in February this year. My review did not reach the finals (finalists here) so I am free to publish it myself.

According to legend, Gerard K. O’Neill, the author of The High Frontier: Human Colonies in Space, had one particular matchstick puzzle that he liked to challenge every visitor with. The puzzle in question was how to form four triangles with just six matchsticks. The solution is rather simple when you find it out, it is a tetrahedron, a triangular pyramid. But it requires that you move away from the two-dimensional thinking of placing matchsticks flat on a table and instead see the problem in three dimensions.

Three dimensional thinking is what High Frontier is all about. Before becoming a popular writer Gerard K. O’Neill was an acclaimed physicist and a prolific writer of scientific papers. His major work as a scientist was his fundamental research in particle physics in the 1950s and 60s, research that contributed to the development of particle accelerators and colliding beam physics.

But particle physics was only his first career. O’Neill was an avid pilot and a great admirer of the US space program. He applied to the Apollo program as a scientist astronaut and went through testing and some training but in the end he was not selected. Instead he found ingenious ways to put space exploration into his graduate teaching.

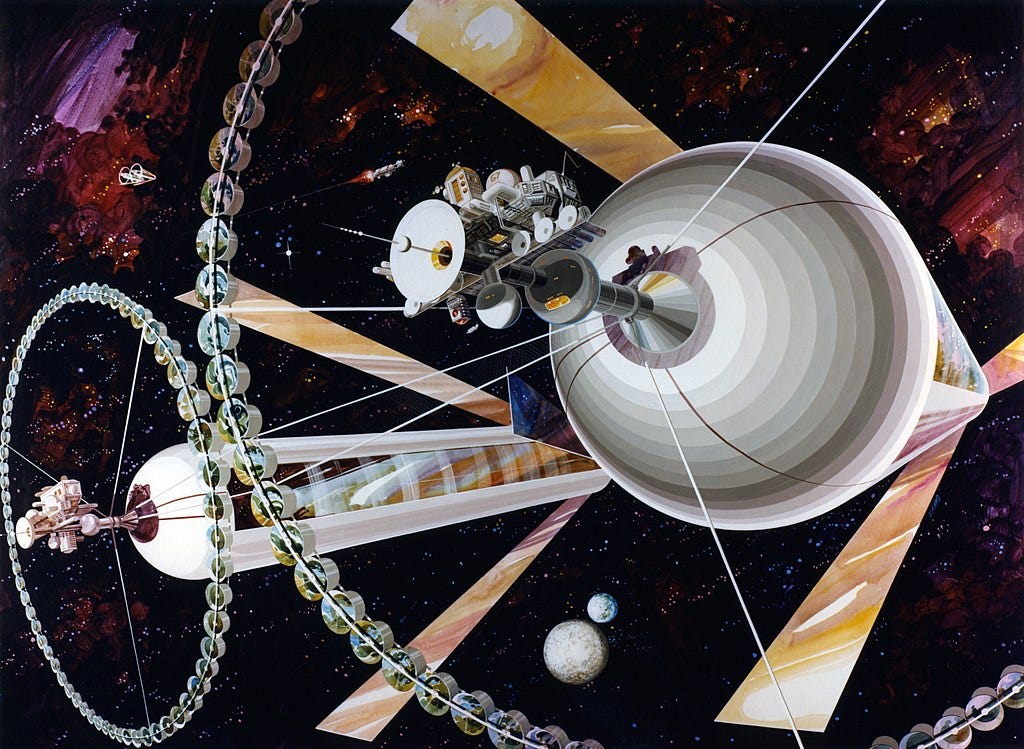

In the late 1960s O’Neill was teaching physics at Princeton University. This was at the height of the space era and as a way to inspire his students he set up assignments where they would calculate the feasibility of different types of space habitats. These space habitats were mostly different types of pressurized spheres and cylinders, rotating to create an artificial gravitation on the interior surface and using mirrors to direct sunlight to the habitable inside.

To the surprise of Professor O’Neill (and presumably to his students too) these theoretical constructions proved very efficient at recreating a liveable environment for humans. And they were not that difficult to construct even with the technology of the early 1970s. This triggered years of dedicated research on the part of O’Neill and he produced numerous scientific papers on different types of space habitats and the ways in which they could be constructed and space thus colonized.

The general principle he settled on is quite straightforward. Conventional rocketry is used to establish a space mission mining resources from the Moon. The Moon’s lesser gravity and lack of atmosphere makes it far cheaper to retrieve resources from there than from Earth (later iterations of the concept use asteroid mining instead of lunar mining). These resources are transported to free space where an industry is set up to convert raw materials into large space habitats. These habitats are then settled with colonizers from Earth.

O’Neill spent a good part of the 1970s producing scientific papers and canvassing support from the scientific community for his ideas for space colonization. In general he was well received by scientists and the minority of the population with an active interest in space exploration. But this was the 70s and public interest in space was waning as rapidly as the funds in the public purse. In short, his grand ideas went nowhere.

That was when he decided to take the issue to the wider public (and, one must assume, to the public’s politicians who were the ones actually holding the purse strings). High Frontier was published in 1977 as a popular summary of his research of the last couple of years. Instead of deep technical discussions it focuses on the social and economical advantages of space colonization. The book was illustrated with dramatic artwork by NASA artists Don Davis and Rick Guidice, whose drawings of massive space habitats filled with lush greenery and exquisite architecture was surely intended to show the Herculean dimension of the task at hand but also the fabulous payoff that could be had.

As the title suggests O’Neill wanted to make space colonization a continuation of previous American colonization of the West. In part this was surely a shrewd marketing gimmick. Readers should be won over with the adventure of a new world to conquer for humanity. But it also reflects deeply held beliefs by Professor O’Neill himself.

O’Neill reasoned that war and conflict on Earth was fundamentally linked to the scarcity of resources and available land. This was the 70s and oil crisis and resource scarcity were regular subjects in the news. In intellectual and academic circles neo-Malthusianism was a serious business.

Against this background O’Neill painted a rosy picture of frontier society. A place where resources are practically unlimited and nothing is holding people and their innate abilities back, a place where everything can be created with hard work, even new land for colonization.

While High Frontier is not an overtly technical book, O’Neill was still a scientist and the technical aspects of the endeavor are given ample space. Space colonization à la O’Neill was built around the assumption that resources were available in space itself. In High Frontier these resources are to be found on the Moon. The Moon has only a sixth of Earth’s gravity which makes it considerably easier to launch cargo to space from there. But above all the Moon has no atmosphere which means it is possible to launch objects from the lunar surface directly into space with no loss of velocity due to air resistance. O’Neill imagined lunar resources would be transported to space in great quantities using solar powered electric railguns on the lunar surface.

In space the lunar resources would be mined for usable materials, materials from which it would be possible to construct space habitats for human habitation but also agricultural units for food production and industrial areas where everything a modern society would need to sustain itself could be produced.

Despite relying heavily on the Moon, O’Neill’s plans still required access to a lot of resources from Earth. If nothing else he dreamed of millions upon millions of earthlings emigrating to space, something which would require significant transportation capacity from Earth’s surface. In 1977, the hope was that this transportation capacity would come from NASA’s still not inaugurated Space Shuttle Program. The space shuttle being both large and reusable seemed to fulfill the dream of cheap access to space. O’Neill ambitiously calculated that a space shuttle would be doing fortnightly trips with 150 colonists each time. Reality would show that this was wildly over-optimistic and the measly capacity of the actual space shuttles would be more culpable than most in scuttling O’Neill’s dreams of space.

Even had the space shuttles been as efficient as promised it would still have cost several fortunes to transport the necessary equipment and people to space. In order to sustain the colonization effort space had to offer something to Earth in return. Professor O’Neill had a solution to this as well. While it is not feasible to export physical products from space back to Earth there is one asset that is amply present in space but seems to be constantly lacking on Earth, namely energy.

In 1977 solar power was not really a serious contender for energy production. Photovoltaic cells were rudimentary and solar plants using mirrors and steam turbines were cumbersome. But even compared with today’s sophisticated solar industry, space has some major advantages when it comes to energy production.

For one, there is no night in space, nor any clouds. The sun always shines. And it does so with full force, not being hampered by atmosphere or other obstructions. Almost as important, at least to Professor O’Neill, is that the zero gravity in space makes it far simpler to put up giant constructions. While a solar plant on Earth needs elaborate, and expensive, scaffolding to stay on the correct place, a solar plant in space can consist of hardly more than strategically placed tin foil around a centrally placed steam generator.

O’Neill envisaged this type of gigantic solar plants placed in a geostationary orbit above the same spot on Earth, converting sunlight into electricity and beaming the electricity down using microwave beams. Microwave beams also need a collector down on Earth to receive the energy. But while photovoltaic cells that collect light are complicated and expensive a microwave receiver can consist of nothing more than a sparse wire mesh. Safe microwave radiation needs to be very weak and the collector thus needs to be very large. But if the mesh is placed on poles then normal land use, for example farming, can still be maintained below the collector.

Using this plan O’Neill hoped not only to solve Earth’s energy problems once and for all, he also hoped to generate enough income to fund the entire space colonization project. We still do not know if this would have worked out, because humanity never colonized space or constructed celestial solar power plants. We do know that no one person or organization believed in O’Neill’s theories enough to put up the necessary capital.

For capital was needed. In great quantities. Professor O’Neill was always, probably for good reason, vague about the actual sums necessary. But there can be no doubt the number was truly astronomical. The only entity able to put up enough capital to even contemplate a space colonization program was the government. And for the government to make such investments it needed strong support from the general public.

Alas, the time for grand public projects had already passed by the time Gerard O’Neill published High Frontier. By 1977 the collective optimism of the 1950s and 1960s had petered out and been replaced by counter-culture and, in the 1980s, rampant individualism. NASA made a big bet on the hugely costly space shuttle program and when that failed to live up to its promises the public appetite for gigantic space programs was non-existent.

High Frontier can be read as an elegy of technology optimism, an elegy of a time when problems could be solved by scientists leading grand projects for the benefit of all mankind. As such it is a history of a future that never was. It is very 70s.

But it can also be read as a concept of a future that is still within the reach of humanity. This is the optimist’s reading. And for the optimist this concept is more within reach than ever. New technology has made space exploration considerably easier than 50 years ago. And spaceflight is slowly getting both cheaper and more accessible due to new business models.

Gerard O’Neill would have been flummoxed had he been told that the space shuttles of the 2020s would be run by private corporations. The Apollo program used a fair amount of private contractors to get its astronauts onto the moon, but they were never anything else than contractors. The government and the government’s organizations were always firmly in charge.

What development there is in the space industry these days has been driven by private capital. And private egos. This makes for a messier world, but also a more interesting one. In the days of old there could usually only be one grand project at a time, an Apollo program when the mission was the moon, a space shuttle program when the mission was space colonization. If this mission failed there was nothing else.

Most of today’s hype is centered around returning to the moon and a mission to Mars. In no small part driven by the most charismatic of the space billionaires, Elon Musk. But the upside of the messy private competition is that there is always someone else ready to make a run for it if the leader stumbles or even falls.

Internet lore has it that Jeff Bezos, founder of Amazon and also, as Mr Musk, the owner of his own spaceflight company, was a student of Professor O’Neill at Princeton in the 1980s. This might be an exaggeration but Mr Bezos did attend Princeton at a time when Gerard O’Neill was a professor there. More importantly, Mr Bezos has been very clear about his admiration for Gerard O’Neill and his ideas for space colonization. Other legends even state that he only founded Amazon as a way to fund his space endeavors.

Be as it may with that, but there is a real possibility that Gerard O’Neill’s visions will one day come true, at least in some form. But while O’Neill imagined a collective effort by humanity to conquer space, today space seems more likely to be conquered by the kings of capitalism. Will that make the newly conquered lands in space a monarchy? That will require another book to sort out.

Why would corporate colonisation of space be more likely to be monarchical than government colonisation?