The Congo wars revisited

The two wars in Congo have been called the great war of Africa. They were not that great and were hardly even wars.

A war is the violent clash between two or more societies. As such, they are at the sharp end of group evolution. War is what determines which groups will thrive and which will founder.

For that reason alone wars are worthy of studying.

Then, of course, there are the wars which are not very evolutionary at all. Because they are not fought between discernible opponents. Or because they are not particularly violent. Or because they are just one big mess. The Congo Wars tick all these boxes.

In an African context the Congo Wars are no outliers. There have been surprisingly few wars in Africa and those few have been confused affairs. But why is that? Geography is key. Historically, high disease pressure has kept African population density low and a difficult environment has kept these populations isolated. This has put a lid on both the ability and the willingness to make war. In more modern times the big stick of colonial powers, both before and after independence, has helped keep tensions civilized.

Western persuasion could not cool tempers in Congo in the late 1990s. In fact, there was not much persuasion at all. But we should not get ahead of ourselves. Let us start at the very beginning.

Kigali, 6 April 1994, slightly after 20.00

Rwandan president Juvénal Habyarimana was coming in to land at Kigali Airport in the Dassault Falcon private jet that the French government had generously gifted him. He was on his way back from a regional summit in Dar-Es-Salaam in Tanzania. With him on the plane was the chief of staff of the Rwandan military, a few minor officers. And the president and several ministers of neighboring Burundi, which president Habyarimana had offered a ride.

When the plane was just a few kilometers from Kigali Airport it was hit by two shoulder-fired surface-to-air missiles and crashed immediately with no survivors. The assassination of the president of Rwanda (for this is what it is most often called, everyone always assumes that the Burundian president was just collateral damage) is one of the great unsolved mysteries of the post-Cold War world. Almost 30 years after the fact we still have no idea who the perpetrators were.

Rwanda at the time was riven by internal conflict. The country consisted of two ethnic groups, the Hutu majority and a large Tutsi minority. There are no real differences between Hutu and Tutsi, they have the same language, the same customs and the same religion. Far back in prehistory (which is not that far in Africa, maybe a few hundred years) the Hutus might have been sedentary agriculturalists while the Tutsi might have been nomadic pastoralists. There are no traces of this eventual history today. The only thing remaining is ethnic stereotypes in which Tutsis are smarter, richer and more arrogant than the poorer but hard-working and dependable Hutus.

In early 1994 the Rwandan government was controlled by Hutus. A Tutsi-led rebel group, the RPF, had waged a civil war since 1990. In late 1993, regional powers and Western donors had forced a peace accord on Hutus and Tutsis alike and when president Habyarimana's private jet was shot down a tentative peace reigned in Kigali.

This peace died more or less the instant the jet hit the ground. According to the peace accord the RPF had a military base in the capital. Shooting started around this base within hours of the president's death and throughout the city roadblocks were coming up. War and violence was coming to central Africa.

Cries from a thousand hills

As soon as open hostilities started again the RPF swept down from their bases in the mountains of the north of the country and quickly gained ground. The Rwandan army only put up weak resistance and after two months the RPF rebels controlled most of the nation's territory.

But this was just the side-show. During the few months of active warfare, especially during the first few weeks, a genocide of biblical proportions took place in government-controlled areas. Ordinary Hutus, the Rwandan army but most of all different youth militias killed Tutsis, but also a fair amount of non-extremist Hutus. The killing was most often done by machete and the typical setup was a roadblock manned by militia that screened everyone who passed for ethnicity (something that was easy since Rwandan identification cards at the time stated ethnicity) and took aside and killed everyone who was Tutsi or otherwise disfavored by the militias and their Hutu power ideology.

The scale of the bloodshed is debated but 800,000 killed is a number often thrown around. This in a country with seven million or so inhabitants ( {African fertility levels has meant that the genocide only made a small dent in the demographics of Rwanda. Today the country is home to over 13 million people.}) . The world community was hardly unaware of what was taking place. The militias did very little to hide their intentions and a UN monitoring mission was present in Rwanda and witnessing the carnage first hand.

Rwanda, the land of a thousand hills, was thus subject to the worst genocide since World War 2. In fact, not even the Nazis had come even close to the efficiency of the Hutu militias who executed 100,000 per week on average over an extended period of time. And all this had happened under the watchful eyes of the UN and the international community. The catastrophe caused some soul searching among global actors. And, even more important for what came next, gave the RPF, the new Rwandan government, significant leeway in how it conducted its business.

Enter Congo from the right

Hutus from Rwanda were terrified of the prospect of ending up under Tutsi rule. Understandably, considering the crimes committed towards the Tutsi. These fears were not unfounded as at least some revenge massacres of Hutus took place. The result was that more than two million Rwandans fled their homeland (again, of a population of slightly more than 7 million). Most of them to eastern Congo (a country then known as Zaire).

Not only did Hutu civilians flee their homeland. Most of the Hutu-dominated government also decamped to Congo and brought with them substantial parts of the former Rwandan army (called FAR, after its French acronym Forces Armées Rwandaises). All of these people now made their home in refugee camps just across the border in Congo while the UN and western donors scrambled to provide food and other supplies to the new refugees.

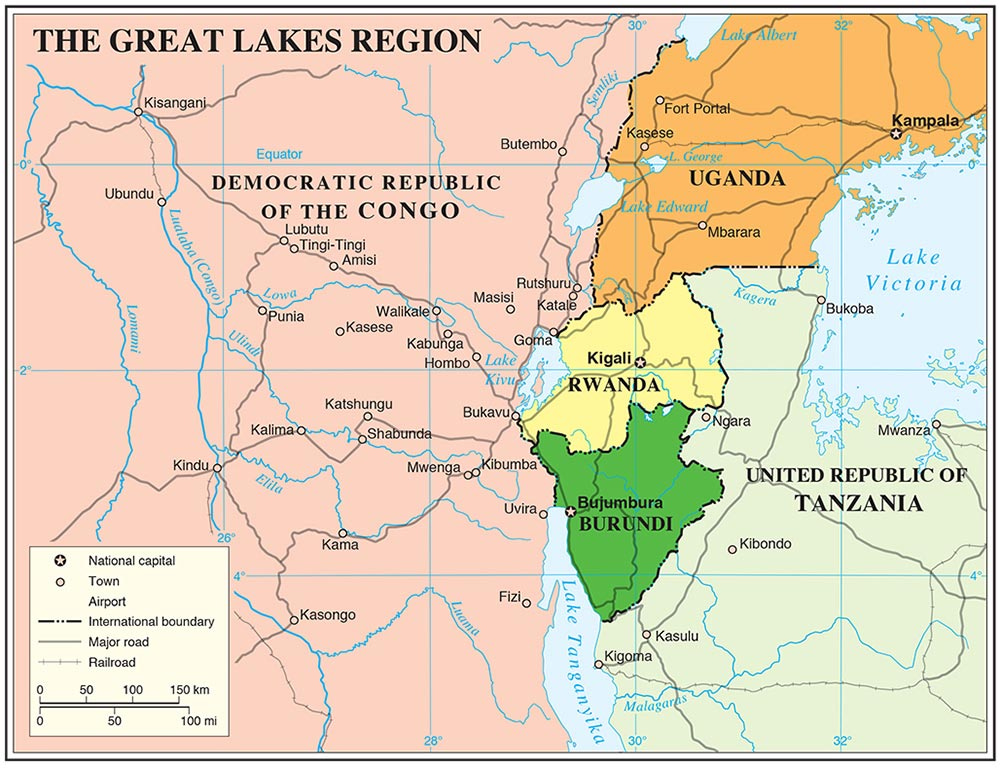

The refugees were for the most part welcomed in Congo. This part of Congo, the Great Lakes region, is closely connected to Rwanda (and Burundi). The area's two main cities, Goma and Bukavu, are both literally situated on the Rwandan border. There are also several million Hutus and Tutsis native to Congo which meant that the Rwandan refugees had little trouble fitting in, socially and linguistically.

The Hutu refugees also had backing from higher up. The larger-than-life president of Congo, Mobutu Sese Seko, was a staunch ally of the former Rwandan government and a personal friend of the late Rwandan president. He ordered all parts of the Congolese government to aid the refugees.

Tear down that wall

Cramming two million people into makeshift tent cities was never an easy project. Even less so in the east of Congo with its famously bad communications. Life in the refugee camps quickly turned awful with a lack of food and raging cholera epidemics. Despite the genocide in Rwanda only being a few months old international news coverage, to the chagrin of Rwanda's new government, quickly turned to the abysmal conditions the refugees were living under.

In fact, the situation was much worse than the international journalists could decipher at the time. The UN provided food and medicine, but had no ability to provide governance. The Congolese army might have been able to project some control over the refugee camps, but they lacked the will. Instead, power in the refugee camps rested solely with the refugee leadership, the former Rwandan military andn politicians, the same people who had orchestrated the Rwandan genocide.

This had far-reaching consequences. One of the most obvious was that the refugee leadership actively discouraged the return of the refugees. Refugees who tried to return to Rwanda were accused of treason and sometimes killed. What should have been a temporary refugee situation was quickly turning permanent.

The Hutu leaders of the refugee camps, labeled génocidaires by the new Tutsi government in Rwanda, also started plotting their return to power. They set out to make life as difficult as possible for the new regime in Kigali. Including using their armed forces to conduct cross-border raids into Rwanda proper.

These armed raids were not an existential threat to the RPF government in Rwanda so much as a nuisance. But they did keep the conflict active which prevented reconstruction and, more than anything, hindered reconciliation after the genocide. Rwanda's answer was to support anti-government groups in Congo, especially those led by the small Tutsi minority there. However, this clearly did not solve the problem and sometime it must have dawned on the leadership in Kigali that they needed a more long-term solution.

The most African Africa

The country I have hitherto called Congo has a lot more to its name than that. The very name Congo comes from the Kongo people that live on Africa's Atlantic coast close to the equator. This area came to be known as the Congo by early European colonists. It was not of that much interest since the tropical lands were unsuitable to European colonization and the disease pressure made even exploring it a daunting task. For hundreds of years Europeans stuck to a few trading posts on the coast where they traded industrial goods for slaves.

This changed in the late 19th century when European ambitions had grown significantly and technological progress made new ventures feasible. Africa was cut up in colonial empires. Something that also happened to the coastal colonies of Congo that were divided in a northern part, French Congo, and a southern part, Belgian Congo (the Portuguese colony of Angola further south also got a significant portion).

Looking from the coast France seemed to get the bigger chunk, they got the part north of the Congo River, an area which became known as French Congo. The area south of the river consequently became Belgian Congo. But in the late 19th century it was inland Africa that was of interest and the Congo River makes a long detour north as soon as it leaves the coastal plain. Probably, but not certainly, France and Belgium were aware of these geographic quirks when they partitioned the land. Anyway, the result was that Belgium ended up with the main part of central Africa.

The Congo River is the third largest river in the world and should be a major transportation artery. In the 19th century it was not. The reason for this is that the Congo River makes a steep descent on its last leg towards the ocean. Most notably at the Inga Falls where the river drops 100 meters in a matter of kilometers creating violent rapids that no boats can pass. Someday these rapids might be the site of the world's largest hydro power plant making Congo an energy powerhouse. But that day is still somewhere in the future.

Except for the rapids close to the Atlantic, the Congo River is rather tranquil and well-suited to river traffic. The two colonial powers therefore used the new technology available to them and built railroads to above the rapids where they founded cities with river ports. For this reason the capital of French Congo, Brazzaville, lies exactly opposite the capital of Belgian Congo, Kinshasa, on their respective sides of the river. Each capital city also has its own railroad down to its respective Atlantic port.

The most African dictator in Africa

Belgium became famous for ruthlessly exploiting Congo for its own economic gain. This was true but Belgium, as all colonial empires, also made significant investments in its colony, especially in infrastructure. Overall, as a colonial power, the Belgian one was not one the better. When decolonization struck Africa in the 1950s and 60s, Congo was mostly unprepared.

Most of all, there was a dearth of Congolese leadership. Belgium had consciously not cultivated an indigenous cadre of leaders. Instead relying on European administrators for everything. This was most obvious in the colonial army, which had plenty of African recruits but not a single African officer. All officers were white Belgians. Naturally, this led to some problems when the white Belgians were supposed to return to Europe.

Belgian Congo declared its independence in 1960. Independence was messy from the start. The new government, led by the idealistic Patrice Lumumba, was not really up to the task. The army mutinied almost immediately and the country rapidly descended into chaos where the central government variously fought separatist guerillas, remaining white settlers and its own army.

Outsiders also poured in. Belgium sent troops to defend the white settlers and also supported several separatist movements. The Soviets sent weapons and a contingent of Cubans which included a certain Che Guevara, who utterly failed in his attempts to foment a Marxist revolution in eastern Congo. Then there was an armed UN mission, the very first in UN history, that tried to not take sides in the internal conflicts and thus ended up fighting all parties at one time or another.

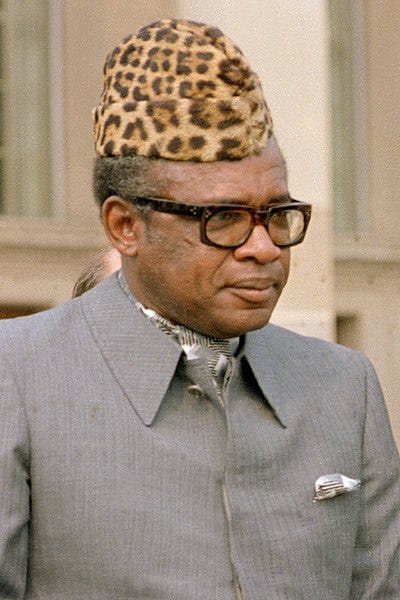

This was the Congo Crisis and for some time it looked like Belgian Congo would collapse under its own unmanageability. Much responsibility fell on the chief of the Congolese army, a man who had been sergeant (remember, no African officers in Belgian Congo) prior to his promotion to army chief. This was Mobutu Sese Seko.

Mobutu used his position as the head of the army to meddle in politics. Already in September 1960, only a few months after independence, he made his first coup d'êtat, to solve a gridlock between the prime minister and the president. Mobutu's army was not strong enough to defeat the various rebellions around the gigantic country. But it was sufficient to project power in Kinshasa.

Some remnants of rebellion would persist in eastern Congo into the 1980s. But the Congo Crisis is usually regarded as having ended in 1965. That is the year when the last main rebellion, the Simba rebellion, was defeated by Mobutu's army (and Belgian paratroopers). It was also the year that Mobutu made his last coup d'êtat, clearing the plate of all other politicians and declaring himself president of the country and of the only legal political party. Congo had become a stable dictatorship.

Mobutu tried to rule as a successor to the still popular Patrice Lumumba (who had been killed in 1961). This meant copying Lumumba's idealistic pan-Africanist ideology and trying to do something pragmatic about it. In Mobutu's version this meant Africanizing his country, including changing its name from its admittedly African name Congo to the presumably even more African Zaire.

Mobutu also Africanized himself. He built a giant Africanesque palace for himself in the jungles in the north of the country. He was also very fond of African fashion, which in his case meant a lot of leopard print. Or rather leopard fur. A leopard fur hat became something of his trademark.

Being a dictator who liked leopard print Mobutu did not have to stop at his own hat. Among the more unusual things he did was to order at least parts of his army to ditch its usual camouflage and instead adopt leopard print fatigues, as in the image below.

As dictators have a tendency to do, Mobutu became more erratic, and more flamboyant, as the years passed. In 1994 he filled the role of crazy African dictator perfectly. His country had seen no real economic development since independence more than 30 years earlier and every echelon of society was completely corrupted. Mobutu had, however, a knack for playing out different factions against each other and riding on top of them all. That had kept him in power for three decades, but now the whole edifice had started to look ramshackle.

Hiding an entire war

Mobutu shared another characteristic with many other old dictators: he had difficulty separating his own interests and his country's interests. When his Hutu friends were chased from Rwanda he found it obvious that he should welcome them in Congo. They were his friends after all. That it could come with risks for his country was not an important issue.

The welcoming of Hutu extremists in Congo came with the very real risk of antagonizing the new government in Rwanda. Something it did very effectively. The Tutsi leaders in Kigali were quickly exasperated by the situation. Not only had they short tempers, they were also experienced guerilla fighters and did not hesitate to solve problems violently.

This should not have been a great problem for Congo. To be sure, few in Congo saw Rwanda as a serious threat to their country. A quick glance at a map explains why. Congo is a big country and Rwanda a small one. In fact, Congo is quite exactly a hundred times larger than Rwanda by area. Surely, a minion like Rwanda could not ponder taking on a giant like Congo.

But this was exactly what was happening in Kigali. The Rwandan government had decided to invade. But since it is not politically possible to just invade a neighboring country (unless you have a permanent seat at the UN Security Council) they needed some sort of cover. Not that much cover. The Rwandan genocide was still fresh in memory and the international community was prepared to cut Rwanda quite a lot of slack when it came to dealing with the perpetrators of said genocide.

Rwanda decided to work under cover of an indigenous Congolese rebellion. This was not entirely implausible since rebellions did flare up regularly in the vast and ethnically diverse Congo. To get the rebel group they wanted the Rwandans created their own, the Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo, better known under its French acronym AFDL.

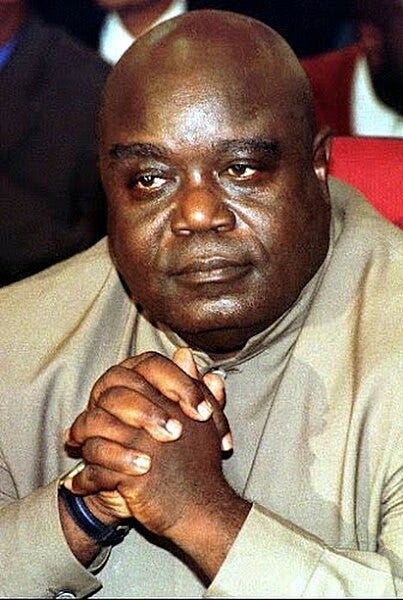

The AFDL lacked any attributes of normal rebel movements, like followers or even a program. It did, however, have a leader. The Rwandans had found a certain Laurent Kabila in exile in Tanzania. Mr. Kabila was a veteran from the Simba rebellion of the 1960s, a hibernated old-school Marxist who was out of luck in the new post-Cold War world.

Laurent Kabila was a long-time enemy of Mobutu and was presumably not that hard to persuade to lead the new rebellion. He had a ragtag band of exiled rebels he could count on but his main asset in the eyes of the Rwandans was probably that he had some sort of name recognition in Congo.

Charge of David

In October 1996 the time had finally come for action. In the eastern Congolese province of Kivu-Sud the Banyamulenge rose in rebellion. The Banyamulenge were Tutsi who lived in eastern Congo. Their rebellion was funded by Rwanda and their troops were trained and equipped on the Rwandan side of the border.

The use of indigenous rebels at first was a ruse to trick the many Western journalists and aid workers present in eastern Congo that the fighting was an internal Congolese business. But the Banyamulenge rebels pouring in from Rwanda were very soon followed by regular Rwandan soldiers.

The primary objectives for the Rwandan forces were the Hutu refugee camps just across the border. These were hit swift and hard and to a staggering effect. Neither the Congolese army, nor the ex-Rwandan Hutu army could do much against the motivated and battle-hardened Rwandan troops.

In only a few weeks the Rwandan forces had routed all resistance and taken control of all refugee camps. The refugees that submitted to the invaders were quickly sent back to Rwanda. Some analysts have even suggested that the main objective of the war was for Rwanda to restore its demographic fortunes after genocide and wild flight had severely depleted its population.

Many refugees did submit to the invaders and returned to Rwanda. But a large proportion, at least several hundred thousands, did not and instead fled west deeper into Congo. A cat and mouse game ensued where the Hutu refugees fled westwards, often through dense jungle, while the Rwandan forces followed. When the Rwandans caught a group of refugees they often initiated a massacre. As in the rest of the Congo Wars, no firm numbers are available, but at the very least, tens of thousands of Hutu refugees were killed this way. Even more perished due to disease and starvation while trying to navigate the inhospitable jungles of east-central Congo.

Something that the Rwandan forces only seldomly bumped into on their westward hunt was organized resistance. The Congolese army had melted away almost at the first sight of the enemy. Neither was the civilian population hostile to the invaders. By this time Mobutu was so widely despised that any rebellion, even one clearly orchestrated by a foreign country, was welcomed.

A geography lesson during a lull in the fighting

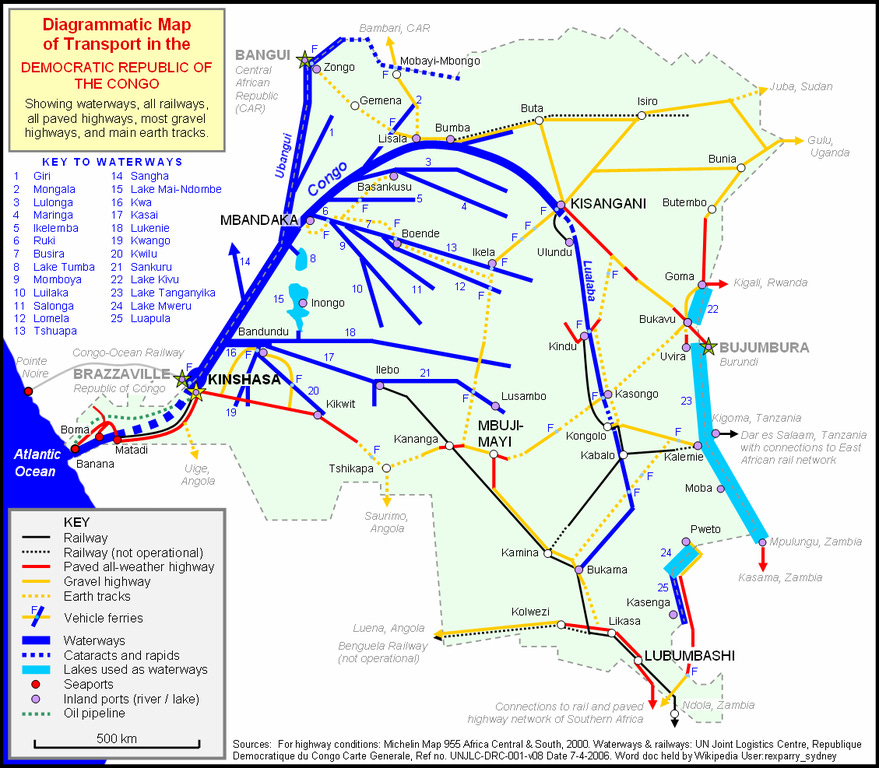

It took the Rwandan army the best part of two months to take full control of the eastern Congolese provinces of North Kivu and South Kivu. After that the fighting mostly died down. This was not due to any peaceful intentions on the part of the invaders. Rather it was due to fierce resistance from a difficult opponent. Not the Congolese army, of course, they hardly put up any defense at all. The fierce resistance instead came from Congolese geography combined with the woeful state of Congolese infrastructure.

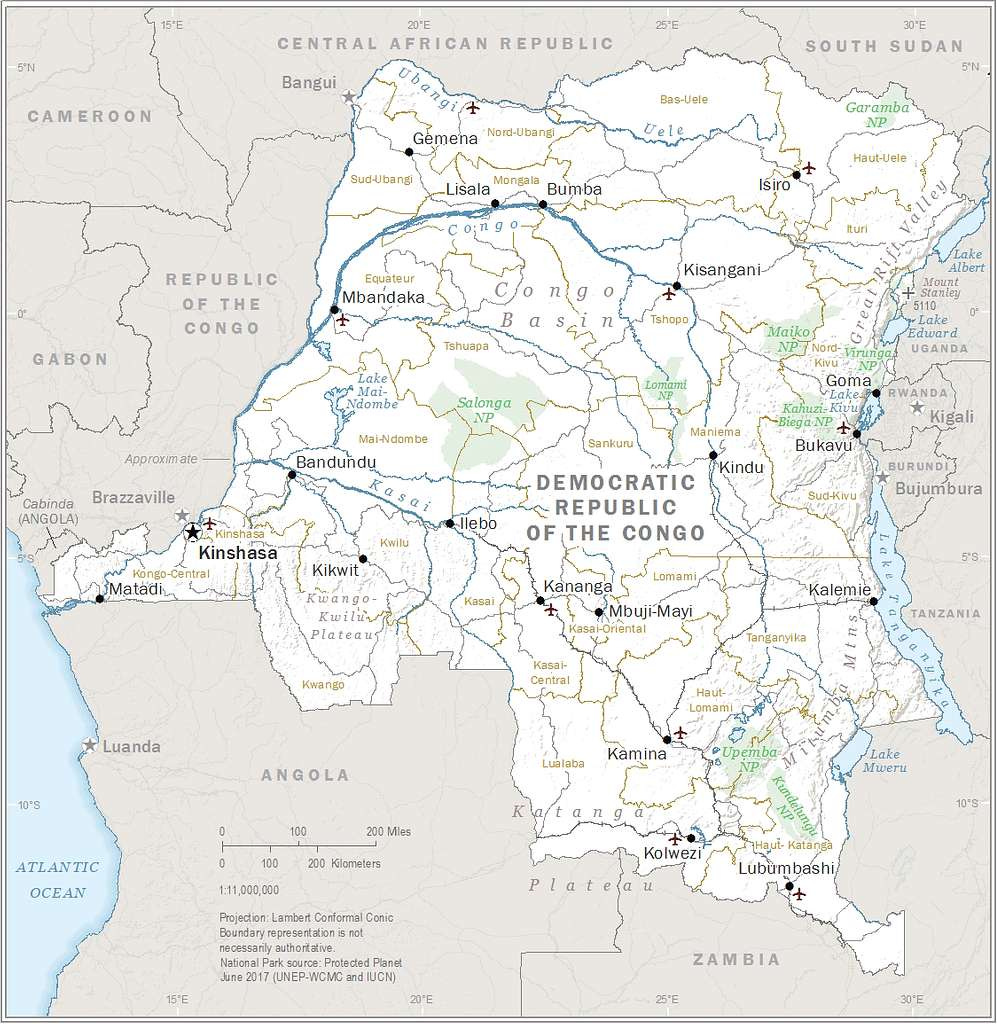

Congo is a strange beast of a land. It sits more or less smack on the equator and a large part of the country consists of tropical rainforest. It is also gigantic. At 2.35 million km² it is three and a half times the size of Texas.

The one thing (tenuously) holding this vast country together is the Congo River. The Congo River basin and the lowland rainforests surrounding it is the most important part of the country. But it is only one part. The two other major parts of the country are the savanna highlands in the south of the country, the area usually called Katanga and whose separatism played a large part in the Congo Crisis in the 1960s.

The third major part of Congo is the eastern uplands, hilly areas in the far east of the country on the border of Uganda, Rwanda and Burundi. This area is part of the Great Rift Valley running through eastern Africa and lies on the western side of the African Great Lakes created by the rift. Due to volcanic soils this area is very fertile which has led to high population densities.

Communications between different parts of Congo are always complicated. The Congo River is an asset, but it has its limitations. From Kinshasa it is smooth sailing upriver to the city of Kisangani. After Kisangani there are rapids making shipping difficult. For that reason it is not possible to use the Congo River to get from Kinshasa and the ocean to the economically important Katanga region in the south. The Belgians solved this problem by building a railroad from Ilebo, a river port on the Kasai River (a tributary to the Congo River), all the way to Lubumbashi, the main city of southern Congo.

Kisangani is not only where the Congo River rapids begin. It is also the gateway to eastern Congo. From Kisangani there are several roads (most of them unpaved and thus unusable during the rainy season) leading east to Goma and Bukavu, the main cities of eastern Congo. But eastern Congo has always had better connections to neighboring countries than to Kinshasa and the rest of Congo. From Bukavu it is 1500 km to Kinshasa as the crow flies and much further using the abominable Congolese infrastructure. From Bukavu to Mombasa, one of the main east African ports, it is only 1200 km on comparatively good Tanzanian and Kenyan roads.

When Rwanda had consolidated their hold on the Kivu provinces in the east they had a strong position. Due to the dearth of infrastructure the Congolese army would have a very hard time mounting a counter-offensive from the central parts of the country. This was strictly hypothetical, however. No counter-offensive was coming from the Congolese side. The nation of Mobutu was crumbling from the inside and was unable to defend itself.

Goliath falls

It is unclear what objectives Rwanda had with its initial invasion of Congo. It is plausible that they only intended to occupy and de-Hutufy the eastern parts of the country. When they discovered that Congo could not put up any meaningful defense they might have become emboldened and opted for a change of plans. But this is only speculation.

Something else happened in the lull of the fighting at the end of 1996: Other regional players made the same discovery as Rwanda, namely that the state of Congo was defunct. From the start Rwanda had had the backing of its neighbors: Uganda and Burundi (only Uganda actually sent any troops, the backing from Burundi was logistical only). But by early 1997 a new ally had come forward: Angola.

Angola, Congo's southern neighbor, was not a minnow like Rwanda but a major regional power. The government of Angola had a very good reason to dislike Mobutu's regime since he had been supporting the Unita rebel group that fought for power in Angola. Since Angola was embroiled in a civil war of its own it was not able to send many troops, but it did send some, and its size and position made it a very valuable ally.

During the lull in the fighting Rwanda had also tried to bolster the AFDL as a serious fighting force. This was done by recruiting large numbers of soldiers in eastern Congo, using Rwandan officers to quickly train them. A large proportion of these soldiers were child soldiers. This was no mistake but a conscious policy on the part of Rwanda and Laurent Kabila. Child soldiers, or more correctly teenage soldiers, were seen as more loyal than adult soldiers and hence more dependable. They were not better soldiers, however, and thousands would die in futile frontal assaults on government positions.

In February 1997 the AFDL/Rwandan/Angolan/etc offensive started anew. The Mobutu regime crumbled almost without a fight. The geography of Congo proved a greater obstacle than government troops but the rebels still reached Kinshasa in May, after which Mobutu fled the country and the rebellion was over.

Another thing slowing down the advance towards Kinshasa was the Rwandans’ continued massacres of Hutu refugees. Something that continued more or less all the way to the Atlantic Ocean. According to Amnesty International 200,000 refugees were murdered in this way.

Out with the foreigners

Laurent Kabila was sworn in as the new president of Congo. He quickly showed himself to be very much like the old president of Congo. Institutions were still out of fashion and personal bonds remained the preferred way of getting anything done. Corruption remained rampant.

In contrast to Mobutu, Kabila was not aloof or flamboyant and instead more down-to-earth. This gave him a good understanding of the grievances of ordinary people, at least ordinary people in Kinshasa, where he was located. Unfortunately, he could not do much to alleviate the economic problems that were foremost on most people's minds. That would have required economic reforms that an old Marxist president of an inherently corrupt state neither could nor wanted to implement.

There was something else that upset the Congolese and which Kabila actually could do something about. After the successful rebellion the Rwandans had remained in Congo. Rwandan officers had high positions in the Congolese army and Rwandan soldiers patrolled the streets of Kinshasa. There was significant friction between the mostly rural and provincial Rwandan soldiers and the urban and cosmopolitan residents of Kinshasa.

When president Kabila felt he had consolidated his power, something that was not that difficult considering that hardly anyone liked Mobutu, he simply ordered all foreign troops out of the country. This happened in July 1998, just over a year after his ascent to power. The foreign troops, which were mostly Rwandan, grumbled but complied.

While the Rwandans had obediently left when ordered to, they seem to have had no real intention of giving up their influence in Congo. Only a few weeks after the ousting of the foreign troops a new rebellion emerged in eastern Congo. The Banyamulenge, the Tutsis of eastern Congo, once again rose in rebellion and once again arms and regular troops swiftly flowed in from Rwanda and Uganda. The Second Congo War had begun.

War at last

The Congolese army was still not much of a fighting force, despite being trained by Rwandan officers for a year. When the Rwandans invaded the country president Kabila realized there was not much to stop them militarily, instead he turned to rousing speeches calling for a citizen's war against the invaders. This had no effect on the battlefield but it lead to the lynching of a number of ethnic Tutsis on the streets of Kinshasa.

As in the First Congo War the main obstacle to Rwandan progress was not the Congolese Army but rather the lack of Congolese infrastructure. But this time the Rwandans thought they had a solution. In a daredevil move rebels and Rwandan regular troops commandeered three airplanes from eastern Congo and ordered them to fly right across the country and land at the Kitona army base on Congo's Atlantic coast.

The move was risky since Kitona was about as far from Rwanda as possible and the base was controlled by Congolese troops. But the gamble paid off. The soldiers at Kitona were mostly former Mobutu troops who lacked both arms and a will to fight. When Rwandan troops streamed out of the airplanes they simply laid down their weapons. Having control of an airport in western Congo the Rwandans could airlift several thousand troops to the proximity of Kinshasa and directly threaten president Kabila and his regime.

Even in western Congo the Congolese army could not muster much of a resistance and the situation looked bleak for Kabila. Then the tables turned again. Kabila had appealed for help from abroad. And he got it. Angola, who had been on Rwanda's side against Mobutu, decided to stick with Kabila. They also persuaded Zimbabwe to support the Congolese government.

The deal to defend Kabila's regime went through when Rwandan forces were already in the suburbs of Kinshasa. Zimbabwean troops were airlifted into Kinshasa to aid in the defense. At the same time Angolan forces were attacking the Rwandans from the south. The Rwandans and their rebel allies were trapped and had to fight their way out. Most dispersed into the jungles. Kinshasa was saved. At least for the time being.

To the winner - the spoils

Despite the successful defense of Kinshasa, Rwandan and Ugandan forces still occupied large parts of eastern Congo. With Angolan and Zimbabwean support their chances of quickly taking Kinshasa disappeared. All sides instead prepared for a long conflict. To entrench their positions they created numerous rebel movements that were nominally independent but in practice not much more than fronts for foreign armies.

The warring parties also started to hunt more actively for resources to fund their operations. Already in the First Congo War, Rwanda and Uganda had funneled proceeds from coltan mines in eastern Congo to their armed forces. This exploitation increased significantly with the deadlock of the Second Congo War.

Coltan, a mineral used to produce the rare elements niobium and tantalum, is very expensive and thus easy to smuggle. It shares these characteristics with diamonds, another resource which Congo has plenty of and which were also smuggled extensively during the war. But smuggling was not the only way to make money from Congolese assets. Especially not if you fought on the government's side. Several Zimbabwean companies with close links to the Zimbabwean government received permits to mine copper in the south of Congo. It all looked very much like payment for military services.

Resource extraction gave a meaningful addition to the budgets of the armed forces on all sides. But it probably could not cover the entire cost or even most of the cost of the war. It is thus unlikely that resource extraction was the reason for the war, as some like to state. It did, however, help to complicate the war, forcing belligerents to focus on ways to generate money rather than on winning outright.

In the end - chaos

The focus on resources led the Rwandans to concentrate their forces south, towards the mineral-rich Katanga region, instead of west towards the capital Kinshasa. There were other reasons for this as well. One was disagreements between Ugandan and Rwandan forces. To mitigate these disagreements the Ugandans and Rwandans had split Congo into zones of control, where Uganda had the northern section of eastern Congo and Rwanda the southern. This made it natural for Rwanda to move south, where they were in full control, rather than west, where they would have had to cooperate with Ugandan forces.

The rift between Uganda and Rwanda was not limited to grumbling. The city of Kisangani lay right on the border between the Ugandan and Rwandan zones of control and they occupied the city together. That is, they did occupy it together until June 2000 when full-scale war broke out between Rwandan and Ugandan troops.

Ironically, this Six-Day War between Ugandan and Rwandan forces in Kisangani saw the fiercest fighting of all of the Congo Wars. During six days of battle thousands of soldiers on both sides lost their lives and most of Kisangani was flattened by artillery. The participants did probably not see the irony in it but with some distance in time and place this battle is a good metaphor for the Congo Wars. Foreigners fighting each other on Congolese ground without anyone understanding why they were fighting.

Rwanda won the Six-Day War against Uganda in Kisangani. As they won almost all the engagements they took part in. The reason why Rwanda's soldiers outdid all other soldiers was mostly due to superior morale. The genocide in 1994 had shown why they should fight. Rwanda's small army had also been at war more or less continuously since 1990, which no doubt helped to keep its soldiers alert.

Another win for Rwanda was the Battle of Pweto in the Katanga region. Rwandan forces had pushed southwards in a bid to take control over the southern province and its mineral wealth. Congolese government forces, stiffened by several thousands Zimbabwean soldiers, made a counter-attack close to the small town of Pweto. They were repulsed by the Rwandans and forced to flee across the border to Zambia, leaving all of their heavy equipment behind.

Winning the battle - muddling the war

Pweto was one of many victories for Rwanda. But by then active hostilities were already winding down. The Battle of Pweto took place in December 2000, one and a half years after a ceasefire agreement was signed by all sides in Lusaka, the capital of Zambia.

Obviously, this ceasefire agreement was not very effective. Mostly because Congolese president Laurent Kabila continued to order new offensives in the hope of reconquering all of his lands. But the pressure was on for less warfare and more diplomacy.

The main reason peace was within reach was that no side seemed capable of actually winning. Rwandan soldiers were very good at winning engagements, but the Rwandan authorities had trouble keeping their unwieldy coalition together. There was of course the split with Uganda. But the Rwandans also had major problems keeping their Congolese allies in line. Their main rebel group in the Second Congo War, RCD, split several times. One of the factions even allied with the Congolese government.

Adding to the confusion was the fact that in January 2001, Congolese president Laurent Kabila was assassinated. The assassin was one of Kabila's own bodyguards, who was killed on the spot. Conspiracy theorists speculated as to who could have been the real culprit behind the gunman, with Rwanda, Angola, USA or faceless mining companies all being blamed at one point or another. Most probably, however, the assassin acted alone out of disillusionment after Kabila had executed several of his friends a few days earlier while putting down a (most likely imaginary) coup attempt.

Laurent Kabila had been a master of playing out different factions against each other, which meant that no obvious candidate stood ready to replace him. In the end the power brokers had to settle for a compromise candidate, namely Laurent Kabila's son Joseph Kabila.

Joseph Kabila was seen as meek and easy to control by more shadowy forces. This turned out to be a largely false assumption. Almost immediately he had the audaciousness to drop his father's most destructive policies. Inflation was quickly brought under control and economic activity picked up again in government controlled areas. Joseph Kabila also realized the war could not be won militarily and he let in several thousand UN peacekeepers as stipulated by the Lusaka Agreement, thus ending once and for all large-scale military activity.

The war to start all wars

In 2003 Joseph Kabila headed a transitional government incorporating most of the former rebel groups. In 2006 real elections were held which Kabila's party won but in which the former rebels did respectably enough to not want to return to armed conflict. The UN peacekeeping mission to Congo, MONUSCO, also kept a lid on things.

Which in no way meant that Congo became a peaceful place. No large-scale military offensives threatened to unseat the government in Kinshasa. But around the country rebellion, or just plain banditry, simmered.

The main reason for this is that Congo is simply too large to be ruled effectively. The Belgians managed to keep things orderly but they relied on a fairly efficient, fairly corruption-free cadre of white European bureaucrats to keep the country together. More than anything, the Belgians ruled a much smaller country. Congo in 1960, right before independence, had about ten million inhabitants. Today, 60 years later, Congo is home to more than a hundred million people.

But the Congo Wars also started something not easily stopped. All sides in the wars did their utmost to recruit local manpower. Young Congolese men were given weapons and rudimentary military training. They were told to fight for their region, for their ethnicity or even for their village. And they grew accustomed to provide for themselves through looting and pillaging.

After the wars the country was awash in small arms and militants. And in a huge and diverse country like Congo there are always conflicts ready to boil over into violence. Especially since nothing has really changed since before the Congo Wars. Congo is still poor as dirt and corrupted to the core. And eastern Congo is still much closer to Kigali than to Kinshasa, both geographically and culturally.

The east has been the main area for conflict since the wars officially ended, 20 years ago. This is partly the fault of Rwanda. It has continued to support selected rebel groups in order to maintain influence in regions they deem strategic, most obviously the M23 rebellion which captured and held Goma, the main city in eastern Congo, for a month in 2012.

But the violence has mostly had a dynamic of its own. In Ituri province, in the far northeastern corner of Congo, a conflict between agriculturalists and pastoralists has simmered more or less since independence. But the Congo Wars supercharged this conflict and put lots of arms in the hands of militants on both sides. The result has been a low-level ethnic war fought by militias that still manage to kill hundreds and displace tens of thousands every year.

In many parts of Congo, but especially in the east and south, there are local defense groups called Mai-Mai. These were created during the wars, mostly but not solely by the Congolese government, who gave them weapons and told them to defend themselves against rebels and foreigners. For the most part, these groups have kept their weapons. They were also never part of any ceasefire agreements and fighting involving Mai-Mai groups continue to flare up.

The most egregious case of wanton killing and destruction since the Congo Wars is probably the genocide of the Bambuti pygmies in northeastern Congo. In 2003, at the very end of formal hostilities, militants from the Uganda-backed MLC rebels killed up to 60,000 pygmies for no other reason than superstition. Pygmies in Congo have always been in a precarious position in relation to surrounding Bantu peoples. But this particular genocide could not have happened if not for the availability of arms and the general lawlessness of the war years.

Checking the rankings

How many people died in the Congo Wars? That is about as easy to answer as how many people live in Congo? Which is, not easy at all. There are no censuses in Congo. Most people are still subsistence farmers and are not reached by any government services. Even primary schools in Congo are not run by the government but rather by independent actors, usually churches. If there is no good way to know how many people there are in the country, naturally there is no good way to know how many people that died in the wars.

Which has not stopped people from trying. Using surveys and statistical methods several researchers have estimated the excess mortality stemming from the war. The most well-known of these studies concluded that the wars had caused 5.4 million excess deaths. These numbers are not uncontested but five million deaths is still a number often thrown around.

Death numbers like these place the Congo Wars fairly high on rankings of the deadliest wars throughout human history. And the most deadliest yet of the post-Cold War conflicts. Depending on your viewpoint, the numbers are deceiving. The Congo Wars did not kill five million people directly. Approximations of violent deaths during the war years are much lower, in the region of 300,000-400,000. That number includes the many victims of massacres perpetrated by all sides. I have not seen any estimates of actual combat deaths, but they are probably less than 100,000.

The real killer in the Congo Wars was the disruption of ordinary life due to insecurity. Communications across the vast country mostly came to a halt. Even worse, aid organizations ceased operations in conflict areas, which encompassed large parts of the country for extended periods. This matters since Congo is in many ways a very brittle society. Only 30% of the food consumed in Congo is actually produced there. The rest is imported. Any disruption to food imports (or food aid) will quickly lead to famine. This is what killed most people in the war.

Why Congo?

There are many brittle countries in the world and especially in Africa. How come Congo was the one being subjected to the brutality of large-scale warfare?

The immediate reasons are obvious: Congo was at the wrong place, at the wrong time and just happened to get in the way of the juggernaut that was Rwanda. This is, sort of, the best explanation to what happened.

Countries invading other countries have generally been frowned upon since 1945. The reason Rwanda could get away with it is only due to the genocide in 1994. Congo got support from France, its superpower friend, which tried to use the UN to stop the Rwandan invasion. But all efforts to stop Rwanda diplomatically were thwarted by the US and the UK who quite openly sided with the invaders.

The better question is why Congo, a hundred times bigger and eight times as populous, could not withstand the Rwandan attack. Of course, Rwanda was a formidable opponent, hardened by a decade of war and united by the most atrocious genocide since 1945. But Congo also had significant deficiencies: It was thoroughly corrupt and riven by internal divisions. Divisions that were easily exploitable by the invaders.

Colonialism is often blamed for many ills in Africa. In the case of Congo there is some substance in the accusations. Most things colonial have long since disappeared in Africa. Memories of colonial brutality are almost as faded as the old colonial infrastructure is decrepit. There is one legacy of colonialism, however, that is almost unchanged since independence: the national borders.

The borders of Congo were formalized at the Berlin Conference in 1885. At a time when the geography of Congo was mostly unknown. Against all logic, these borders have remained the same for nearly 140 years. Just as they have in the rest of Africa.

These ancient national borders are a problem in all of Africa, but the problem is arguably the worst in Congo. For the simple reason that Congo's geography is the most hostile to statecraft. Great distances and superb geographic obstacles make Congo a nightmare to rule. General poverty and ethnic differences complete the picture of an impossible nation.

In a better world Congo would be at least three different countries. Katanga in the south, Kivu in the east and the real Congo in the west and northwest. Ironically, this western rump Congo would probably have no problem assimilating all of the neighboring state of the Republic of Congo, the former French Congo.

The differences between western Congo and eastern Congo are vast, in western Congo the lingua franca is Lingala while in the east and south it is Swahili. The geography of western and northern Congo is dominated by lowland rainforests while in the east it is mountainous and in the south savanna.

Compared to Katanga and Kivu, French Congo is almost indistinguishable from neighboring Belgian Congo. It is a Lingala-speaking country dominated by lowland rainforests. To top it off, its capital, Brazzaville, is just across the Congo River from Kinshasa. They are a match made in heaven. Even so, I can not find any serious suggestions of a merger between the two. In Africa, national borders are simply not supposed to be challenged.

An inconvenient truth

Taking the argument further one lands in an unpleasant conclusion: Maybe the real problem in Africa is not too many wars but too few. In Europe, states have grown organically during thousands of years. Organic development in this context is just another word for wars. The national borders of Europe are the product of hundreds of wars, small and large.

This eternal warfare has been bloody and costly but the result is not bad. Europe has a bunch of very stable nation states. Something that can not be said of Africa. Africa's borders have not developed organically. They are artificial constructions decided by colonial imperialists with often minimal knowledge of the geography and demographics concerned.

Imperial overlords did not really disappear with independence. Africa still has them in the form of the UN and the international community. African states are not free to do as they please. If they do not follow international norms consequences inevitably follow.

This is a problem since the international norms are created for mature and developed states. African states are neither mature, nor developed. What works for states in Europe and North America does not necessarily work in Africa.

Competition is the driver of human development, competition between human individuals but also between human societies. Human societies most of all compete for resources. The one who can best utilize the resources will be able to out-compete neighbors with less skill in resource utilization. This way resources will over time drift to where they are used most efficiently. For less developed societies the main resource is land, competition for land means war.

The Congo Wars should have been wars for land. In a world free from colonial overlords the superbly efficient Rwandans should have conquered large tracts of Congolese land and put it to better use. This never happened since the international community and thousands of UN troops put a stop to it (ironically, Rwanda today is the world's foremost contributor of UN troops on a per capita basis). If five million people died in the Congo Wars it is a tragedy. But an even bigger tragedy is that they died for nothing. The wars did not change anything.

For that reason the Congo Wars can never be the Great War of Africa. The Great War in Europe was not only a major war. It was a major war that led to major political changes (especially in Eastern Europe) which set the course towards modern nation states. The Congo Wars were nothing of the kind.

Rather than the Great War of Africa the Congo Wars should be called the Thirty Years' War of Africa. The Thirty Years' War in the 17th century did lead to some real political changes (especially for the Dutch and Swiss) but overall it was a calamitous engagement between innumerable armed gangs who frequently switched sides and overall did as much to plunder the country as they did to conquer it. In that sense it was very much like Congo in the late 20th century.

All information not explicitly sourced from somewhere else can be expected to come from the book Dancing in the Glory of Monsters - The Collapse of the Congo and the Great War of Africa by Jason Stearns. Compared to this article the book gives a much more disorderly picture of the Congo Wars. This is amply compensated by the fact that the author, unlike me, has done significant primary research by interviewing hundreds of Congolese and Rwandan participants in the war.

Eager Wood From Eden readers might have wondered what I have been doing for over two months. There are many reasons. First of all, Tove had a bad pregnancy which made her disabled for all of September and October. Since we have a house building project that really needs to move forward I had to spend a lot of time, especially mornings usually reserved for writing, building a house. For the last three weeks Tove has been in rude health, instead she has dumped an infant on me which has increased my child minding duties and also led to a bit of sleep deprivation. But most of all I am still learning the ropes of writing. Two months ago I had recently read a book about the Congo Wars and thought it would be straightforward to write an article about it. Big mistake. When you write an opinion piece you can write pretty much whatever you feel like without much consequence. When you write an information piece, like this one, every piece of information needs to be verified. There is no point in writing a factual text if the facts are not correct. According to the file history I started writing this article on 28 September and only now have I been able to finish it (no, I have not written anything else besides). If any of you readers find this pathetic you are excused, I think so too.

>>For the last three weeks Tove has been in rude health, instead she has dumped an infant on me which has increased my child minding duties and also led to a bit of sleep deprivation.

That's not fair! I didn't dump an infant on you: You threw me out to work.

On topic: I pressed the link https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Effacer_le_tableau on the genocide of the Bambuti pygmies and found about half a page of text. Apparently it is of very little interest that tens of thousands of people and (if I get it right) more than half of a ethnic group were killed off.

One aspect of this that isn't mentioned is that the European ethnicities are to a considerable extent artificial themselves, deliberately created by the states. The case I've seen most written about is France, where Paris imposed its concept of Frenchness, and particularly its dialect, on the rest of the territory. I've read that even in contemporary times, teachers weren't allowed to work in the region they grew up in, to ensure that French remains uniform. And back when the EU was being established, I remember one news story interviewing a farmer, "First I am Provencal. Second I am French. Third perhaps I am European." That's not to say that once such an ethnic homogeneity is created/enforced that it does not cause a coherence of the population.

A contrary example is Bret Devereaux' historical essays. In one he points out that the United States has never defined itself as a nation-state, that is, the homeland of a people with a common descent. (Which accounts for US patriotism centering on the political institutions of the state rather than the nation's deep history.) Much more interestingly, he argues that Rome didn't either, that the Roman conception of citizenship was always a legal one. This, and the pressure of various events, made it easy for Rome to expand citizenship (in various degrees) to wider ranges of people that they'd conquered as a device for obtaining cooperation. Late in the empire, citizenship was extended to all free males. Devereaux argues that this helps account for the long life of the Roman polity (about 2,000 years!) -- unlike most ancient empires, where one kingdom-nation conquered a bunch of its neighbors, who then broke away as soon as the empire inherited an incompetent king. By late empire times, the people of the empire thought of themselves as Romans and had no sense of being violated by Roman rule (even though they surely still saw themselves as ethnically different).