As far back as I can remember, I felt ambivalent towards evolutionary psychology. On the one hand, it was too difficult to explain away. If we believe that 1. a large part of our psychology has genetic origins and 2. our genes were selected by evolution, what else is there to believe in?

Still, I resented the thought of evolutionary psychology for a long time, because it didn't feel right. For example, it was said that on the savanna tens of thousands of years ago it paid off to be lazy when you didn't have anything especially important to do. But I didn't feel lazy: I felt like a maniac workaholic.

For reasons like that I tried to develop convincing arguments against evolutionary psychology. I wasn't very successful. But I tried, and I tried and I tried and I tried.

Cochrane and Harpending to the rescue

Then I somehow stumbled over a book called The 10 000 Year Explosion by anthropologists Gregory Cochran and Henry Harpending. It solved all my problems in one stroke: The solution wasn't less evolutionary psychology, but more. The book explained that the agricultural revolution 10 000 years ago didn't end genetic selection in humans. It turbocharged it instead. Evolution is not mostly about de novo mutations, it explained, but about selection pressure for what is already there. When selection pressure intensifies or changes, significant evolution takes place during only a few generations.

This means that evolutionary psychology has a much bigger task than previously thought: It has to comb through the entire span of human and pre-human history in search for answers. The human mind wasn't created during a few hundreds of thousands of years on the African savanna. It is both a lot older and a lot newer than that. If we want to speculate about evolutionary psychology in any meaningful way, we need to search through history in its entirety.

It is a bit unfortunate that The 10 000 Year Explosion was written as early as 2009, because evidence about recent evolution was scarcer then than after the paleogenetic revolution of the 2010s. For example, like almost all people in 2009, Cochran and Harpending assumed that the Indo-European invaders about 4000 years ago came with their language, their lactase persistence gene and little else. Only from 2012 onwards, the laboratory of Svante Pääbo started to find out that the Indo-European invaders actually killed off or otherwise replaced a large part of existing European populations (see especially David Reich's 2018 book Who We Are and How We Got Here). This information greatly strengthens the 10 000 year explosion hypothesis: during the last 10 000 years, genes were not just selected because some people had more surviving children than others in a Malthusian economy but also because some peoples were better at forming armies and collectively killing the others.

How does it feel?

Not everyone felt the intellectual relief I felt from reading The 10 000 Year Explosion. The idea that evolution continues until this day stirred some controversy because it implies that there could be important (average) differences between different genetic sub-groups of humans. For example, one chapter of the 10 000 Year Explosion launches the theory that Ashkenazi Jews have higher IQ than most other peoples on Earth because they were forced into professions where they needed to read, write and count more than average Europeans. I think that is a very interesting theory. But the possibility that different groups could have different levels of IQ-coding genes is controversial, to put it mildly.

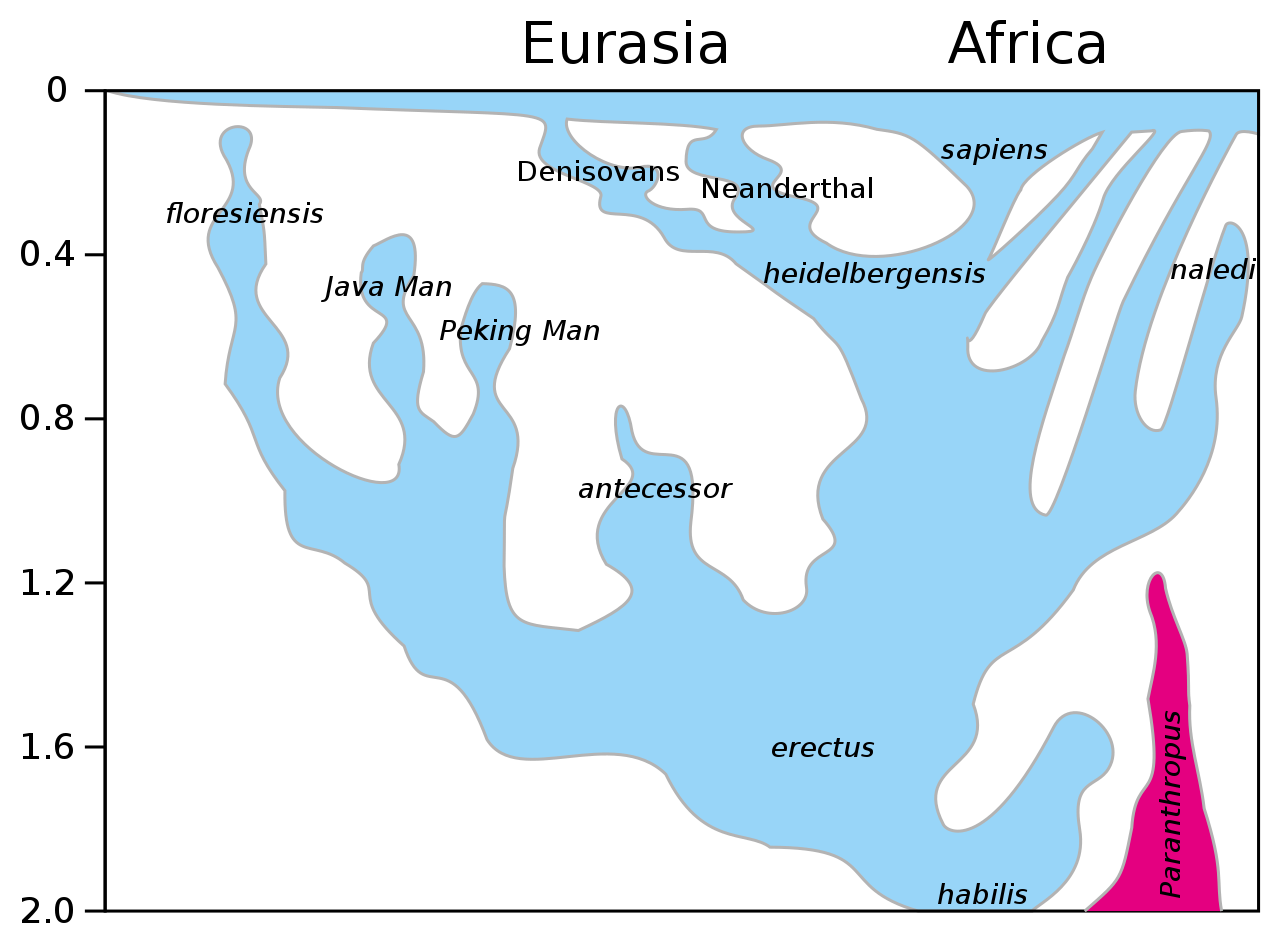

If we shy away from this controversy we can just as well kill off evolutionary psychology immediately (which, no doubt, some people would be happy to do). As this diagram from Wikipedia

shows, there is no single point in human history from which all modern humans branch. The point from which we all stem is further back in history than the existence of Homo Sapiens Sapiens (who is generally said to be no older than 300 000 years). In practice this means that if there has been evolution on humans then there are also evolutionary differences between groups of humans. If we are going to deal with human evolution, we will also have to deal with both human likeness and human difference, however it feels.

Personally, I think it feels great. My younger self’s problem with evolutionary psychology was mostly that it stipulated how I should feel about certain things, just because I was a human (and a human female at that). More detailed evolutionary psychology gives me much more freedom in how to interpret myself in an evolutionary context. For example, I feel very much like a farmer, so I suppose that I got many genes that were selected for after the 10 000 year explosion. But my quiet rejoice over the green foliage around my cultivations makes me assume I carry some gorilla genes that were left behind too.

Why would any sane person speculate this way, someone will probably ask. It can't be proven right or wrong anyway. My answer is, now as always: What else is there to believe in? Freudian psychoanalysis? Lacanian psychoanalysis, whatever that is? Blank slate-ism? Or should I, (the horror!), stop caring about psychology and believe in nothing?

Science based on a loose, speculative theory that can't ever be proven right or wrong is not an ideal, but it still has one advantage: it makes room for educated guesses. Science without theory only makes room for random guesses. Which, actually, describes some important aspects of Freudian psychoanalysis rather well: The theory of the Oedipus complex apparently arose because Sigmund himself guessed that his own childhood experiences were a human universal.

Other aspects of Freudian psychoanalysis precede evolutionary psychology, like Freud's 1930 book Civilization and its Discontents. If psychoanalysis evolved into evolutionary psychology during a hundred years or so, I think that is great progress. If anybody has any suggestions of a theory that could make my guesses even more educated, I'm eager to listen. After all, if I could overcome my resistance to one theory, I should be able to do the same with another.

“Or should I, (the horror!), stop caring about psychology and believe in nothing?”

Though it would be anathema to my younger (as in 39-year-old) self, I think this is probably closer to right/healthy than not. In other words, have all the thoughts you want--host them, entertain them, wine them and dine them, maybe even take them to bed for an impassioned fling--just don’t marry them, don’t wed yourself to them eternally, don’t sacrifice yourself to others to them. Don’t believe in your thoughts.