My take on the Ukraine War

I am spending an inordinate time keeping myself updated on the latest war reports. Why not share some of my findings?

The war in Ukraine is costing the West dearly. That is the message coming out of Russia and I believe there is something to it. The war in Ukraine is a gigantic drain on Western productivity. At least it is a gigantic drain on my productivity.

Tove and I have been writing Wood From Eden for 16 months now. During all of that time there has been a war going on not that far from us. Western Ukraine, where missiles are occasionally landing, is less than 800 kilometers from where I am currently sitting. The Russian exclave of Kaliningrad is not even 400 kilometers from here.

Proximity aside, I have a profound interest in history, especially military history. Right now in Ukraine, the contents of future history books are being created as I write. And we do not even know how it will end. It is all very exciting.

Which is the reason my productivity is suffering. For the last 19 months I have spent about an hour per day reading war reports in one way or another. Not primarily news reports. This war is not waged in newspapers as much as on Telegram. And if it is not possible to get the latest reports from the right Telegram channels it is almost as good to read about what is happening on Wikipedia. Either way, time flies when you are watching history being made.

Of course, spending an hour a day keeping abreast with the military-political situation in Ukraine is nothing. There are countless people spending eight hours a day or more doing precisely the same thing. No matter how hard I try, I will remain an amateur. But, being frank, I am an amateur at almost every subject. Writing about the Ukraine War should be no different than writing about the numerous other subjects I have written about that I know even less of. So, here it is: My take on the Ukraine War.

In the beginning

Russia's invasion of Ukraine on the 24 February 2022 is inevitably a good candidate for the greatest geopolitical error of the 21st century. It would have been easy to say that it has not gone according to plan. But of that we know nothing, because Russia has never published anything resembling a plan. Its intentions with the invasion remain murky.

The closest thing to a mission plan that we have is Vladimir Putin's speech to the nation on the day of the invasion. The speech will hopefully go down in history as the speech of sighs, due to Putin’s 28 minute long sad-face. It is very short on actual statements but Putin still manages to pin down some of his expectations: He expects all Russian soldiers to do their duty, he calls on all Ukrainians to lay down their arms, he tells the Russian people to prepare for more sanctions and he threatens the rest of the world with "consequences you have never seen" if they dare to meddle.

From this sparse information it is possible to make a few educated guesses about the line of thought inside Putin’s head. Clearly, he expected a large share of Ukrainians to support the intervention, or at least not actively resist it. He believed that western sanctions were inevitable and asked the people to bear it. The major risk he saw seemed to be an intervention from any western nation, which is why he reserved the most chilling language to this particular case.

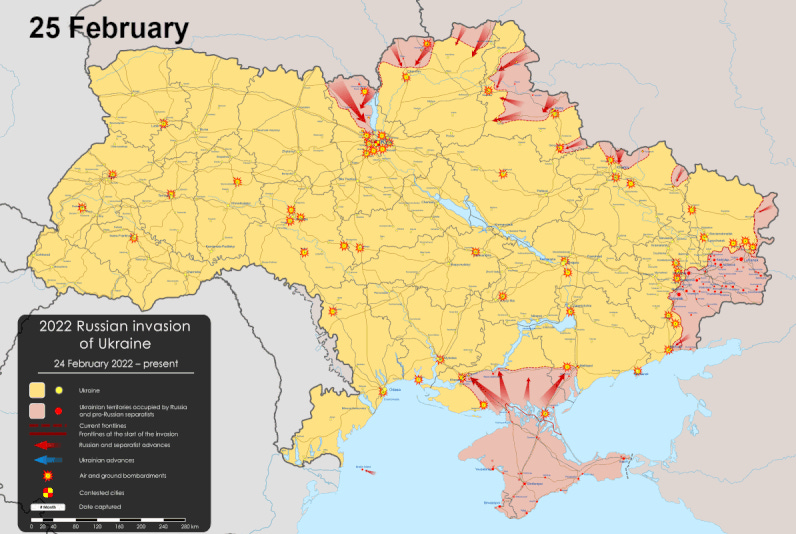

This all fits quite well with what happened on the ground during the first few days. Those early days of the invasion might have looked like a general onslaught from all sides, but this was actually not what happened. The Russians attacked southern Ukraine from Crimea (quite successfully) and northeastern Ukraine around Kharkiv (quite unsuccessfully). What they did not do was attack eastern Ukraine from the area of the Donbas republics. This is a bit strange considering that the protection of the people of Donbas was (and is) one of the few stated objectives of the war. Looked at another way, it does make perfect sense. The Ukrainian border with Donbas was well defended and manned by motivated troops. It was one of the few places where the Russians would have assumed actual resistance to take place, which was reason enough to avoid it.

The attacks in the south and towards Kharkiv were mere diversions to the real action, which was towards Kiev. The Russians attacked Kiev using two thrusts, one smaller from Belarus that moved on the western side of the river Dnieper, and one larger thrust covering a greater distance from Russian territory to arrive at the Ukrainian capital from the east.

But the very first action was from the sky. Almost the first Russian soldiers to set foot on Ukrainian ground were paratroopers that made an airborne assault on Hostomel airport, northwest of Kiev. They were joined a day later by regular Russian troops that had rushed from Belarusian territory a mere 150 km away.

This is a strange way to conduct an invasion. It is, however, exactly how you would behave if you wanted to decapitate a country by quickly taking over all government functions without engaging the enemy's main forces.

Not according to plan

Whatever the Russian plan, it can hardly have played out as imagined. Ukrainian troops scrambled to meet the Russian paratroopers in the Battle for Hostomel Airport which denied the Russians use of the airport. The armored troops joining the paratroopers were likewise pinned down by Ukrainian defenders in the Battle of Hostomel until they retreated a month later.

The Russian forces in the northeast of Ukraine made a mess of their thrust towards Kiev. Maps from the first days of the invasion commonly depicted the whole of northeastern Ukraine as under the control of Russian troops. It was only later that it became clear that the Russians controlled none of the cities and hardly anything beyond the main roads. They had simply bypassed every area of resistance, which turned out to be every city of any magnitude; clearly their orders were to get to Kiev as quickly as possible.

Bypassing all resistance might have seemed wise at the time but turned out disastrously. Logistics became a nightmare when every city, and thus every transportation node, had to be bypassed. It also left plenty of Ukrainian troops in the rear, ready to strike at all vulnerable targets, of which there were many. When significant forces finally reached Kiev from the east, which was almost a fortnight after the invasion started, Ukrainian defenders were well prepared and ambushed the Russian tanks in the Battle of Brovary in Kiev’s eastern suburbs.

The stalemate that followed in March 2022 was agonizing to watch. It was very difficult to discern what would happen. Reports were streaming in about Russian losses, but since the Russians were obviously staying their ground it was easy to dismiss most of it as Ukrainian propaganda. At the same time the Russians seemed to lack a comprehensive objective which made the whole situation very hard to read.

As it turned out, the Russians were taking significant losses. The incomprehensible slogging in March was probably due to inertia in the Russian leadership. The plan had been for a swift occupation of Kiev and a government change in Ukraine. When this plan failed it took the Russian leaders a month or so to make up their minds on what they should do instead.

Eastern tide

The Russian offensive in the south was strikingly effective. With quite limited numbers the Russian forces in Crimea swept all over southern Ukraine in a matter of days. The important port city of Mariupol, 40 km from the de facto border with Donetsk People's Republic, was surrounded and cut off just five days after the invasion. By troops moving east from Crimea, 300 km away.

I do not know why the offensive in the south was much more successful than the offensive in the northeast. There the Russian troops tried to move quickly into Kharkiv, Ukraine's second city, but were rebuffed in the Battle of Kharkiv. Probably it was down to sheer luck. In southern Ukraine the Russians managed to surprise the Ukrainians and were able to move quickly over mostly sparsely populated land. In the north the Russians aimed directly for Kharkiv, a city of 1.5 million people where their small force of less than 50,000 soldiers was simply swallowed by the vast urban agglomeration.

By late March the offensive against Kharkiv had not achieved anything except lobbing a number of missiles into the central city. But the offensive in the south had also been decisively halted. The Russian advance towards Odessa, which might or might not have been a primary Russian objective, had stopped in Mykolaiv and the city of Mariupol was also holding out, despite being cut off for a month.

My belief is that the Russians had no plan B to put in motion when plan A did not work. When the coup d'état move towards Kiev failed it would have been logical to pull back and redeploy the troops to the southern and eastern offensives. This did not happen, which in my view shows that the Russians did not want to simply press on with what they had started but instead waited until they had rewritten the whole narrative.

When the Russian troops finally pulled out from the Kiev area in late March they did so very competently. It was no rout forced by the Ukrainians, but rather an ordered retreat when there was better use for the troops somewhere else.

This somewhere else was neither towards Odessa, nor around Kharkiv. These cities might have been objectives in the primary invasion but from early April they were not that important anymore. Instead the Russians declared that they had initiated the second phase of their invasion which focussed on conquering Donbas and in the process destroying the major part of the Ukrainian army.

From late April the Russians implemented an all-out offensive towards the parts of Donetsk and Luhansk provinces (which together make up Donbas) that they did not already control. This offensive was not without successes. Sievierodonetsk, the last Ukrainian city in Luhansk, fell in June and the Russians were pressing towards Sloviansk and Kramatorsk, the last major Ukrainian cities in Donetsk.

The strategy of redeploying troops from the Kiev offensive to the east had one major disadvantage. By retreating from Kiev the Russians did not only free up their own troops attacking Kiev, they also freed up the Ukrainian troops defending Kiev. These Ukrainian troops were moved east to help with the defense. The result was that the Russian offensive in Donbas was not as effective as could have been expected. The Russian advantage in material, especially artillery, gave them an edge, but not enough to be decisive.

The republic strikes back

As the initial Russian attack force was worn down and as Ukraine mobilized more soldiers and equipped them with gear donated from the west, the balance of power slowly shifted. The Ukrainians were gaining strength while the Russians slowly lost theirs. Even though the Russians had the initiative over the summer the Ukrainians could still make localized counter-offensives, for example around Kharkiv, which was cleared of Russian troops in May.

When the Russian progress in Donbas petered out, talk turned increasingly to a major Ukrainian counter-offensive, which was advertised to take place in Kherson province in the south. Kherson was a natural choice since it was the only place where the Russians had crossed the Dnieper river and their forces on the northern side of the river should thus be easy to cut off and destroy.

By the summer of 2022 Ukraine was also receiving some really fancy weaponry from its allies in the west. Foremost among these were the American Himars rocket artillery. Rocket artillery is nothing new and the Russians have plenty of it (for example Uragan and Smerch). On paper the Russian systems are even better than Himars, with better range and greater payload. What Himars does have is accuracy, it can hit a circle a few meters in diameter at a range of 80 km. Similar Russian systems would be lucky to hit a circle a few hundred meters in diameter at the same range. This accuracy enabled the Ukrainians to take out Russian ammunition depots and logistics nodes from afar while the Russians had very limited abilities to return in kind.

This degrading of Russian assets combined with the inflow of Western weapons gave the Ukrainians the means to meet the Russians head-on in Kherson. Despite this the going was tough and reports about huge Ukrainian losses were common during the late summer and early fall. Even now it is unclear to me if the Ukrainian offensive in Kherson was real or if it was a giant deception.

While the Kherson offensive was ongoing what seemed like minor Ukrainian forces broke through Russian lines close to Kharkiv and made a mad dash for the town of Kupiansk, east of Kharkiv. Due to the local geography (especially the very wide Oskil river) Kupiansk is a transportation hub without which the Russians could no longer support their troops in Izium and Lyman. These forces subsequently folded, fleeing back to Russian lines on minor roads and leaving plenty of heavy equipment behind. I am no military man but to a layman like me it looked like a brilliant strategic move from the Ukrainian general staff.

Politics, Russian style

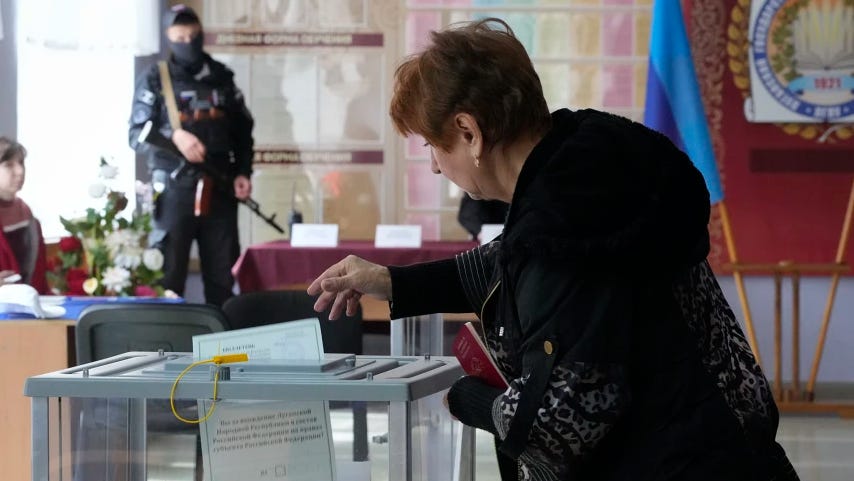

The unquestionable military loss in the northeast sent shockwaves through Russia and led to some immediate reactions. Not necessarily the ones one would expect, but still. Kupiansk fell to the Ukrainians on 10 September. Ten days later, on 20 September 2022, referendums on joining Russia were announced for the four Ukrainian provinces Russia was occupying (Kherson, Zaporizhzhia, Donetsk and Luhansk). These referendums were scheduled to take place only a few days after the announcement, on 23-27 September.

Announcing an important referendum three days before it is set to take place is of course a joke. Had Russia wanted their referendums to have any sort of legitimacy they should have done it some other way. At the moment, legitimacy was probably not very high on the Russian agenda. However, legality might have been. According to information I have never been able to fully verify (not being able to read or write Russian I am often simply unable to find the sources I need for verifications) Russian law stipulates that conscripted troops can only be used within the borders of the Russian state.

After the successful Ukrainian counter-offensive it was clear that Russia needed more soldiers. Since the law prohibited the use of conscripted troops outside Russia's borders, the Kremlin logic determined that these borders had to move to where the fighting was. Hence the very sudden annexation referendums. A partial mobilization of Russian troops was also declared on 21 September, giving just about enough time to hold the referendums and formalize the annexation before the new troops were ready to deploy.

Some people, especially in Russia, still believe these referendums have some sort of legitimacy, despite the short announcement period and despite photos of voters placing their open ballots in the ballot box in the presence of armed Russian soldiers.

It is actually quite easy to disprove these proponents of Russian democracy. Russia is generally not strong on firm numbers but Tass did publish the referendum results including both number of votes and voter turnout. This enables us to calculate the total number of eligible voters for each province, This can then be compared to pre-war numbers of eligible voters, at least for Kherson and Zaporizhzhia, the two provinces that were completely under Ukrainian control in 2019 and thus have complete electoral rolls from very recently.

For Kherson province, Tass gives a total electoral roll of 742,910 voters. For the Ukrainian presidential election of 2019 the Ukrainian vote commission gave an electoral roll in Kherson of 816,138. That is not much of a difference. But at the time Russia controlled all of Kherson province and the numbers still show that 10% of the Kherson population had somehow disappeared from the Russian electoral roll.

In Zaporizhzhia the same numbers were 633,598 according to the Russian electoral roll and 1,354,696 according to the 2019 Ukrainian electoral roll. Here, a staggering 53% of the pre-war electoral roll had disappeared in the Russian referendum. This is not surprising since the northern third of the province, containing about half the population, was at the time of the referendum controlled by Ukrainian forces. Still, it is a bit rich to claim democratic legitimacy for a referendum in which the majority of the population was barred from participating.

Enjoying the cold

The influx of Russian conscripts did not fundamentally change the facts on the ground. They were not able to stop the Ukrainian offensive in Kherson (if they even tried). The Russians left the northern side of the Dnieper in November in an orderly fashion..

Russian propagandists talked up the offensives that would follow once the conscripts had established themselves. In the end this winter offensive turned out to be very feeble. This might have been due to deficiencies in the upper echelons of the general staff. The Russians did make some significant tactical mistakes, for example outside Vuhledar where hundreds of armored vehicles were lost in a matter of days.

But it is also possible that the Russians lacked a will to win, or at least a will to win decisively. This might sound implausible but the current conflict seems to suit the Russian leadership quite well. In Russia these days there is no critical reporting in the media and no organized opposition. But there is plenty of patriotic rallying around the flag and the current government. Put differently, Putin's grip on power is more secure than ever, which might have been the main objective of the operation all along.

This actually sounds quite plausible when you connect the dots. What was the reason for Putin to order an invasion of Ukraine in 2022? There is of course the potential for geopolitical profit. Russia stood to gain a dependable ally between itself and Europe, not to mention millions of new Russian-speaking subjects. All worthy goals for someone with an inclination for realpolitik.

A geopolitical advantage is all good and well. But the Russian leadership are not complete fools. They must have understood that attacking Ukraine came at a steep price in the form of lost diplomatic prestige and severe economic sanctions. Even had the operation gone as smoothly as possible it would still have been far from clear that the gains outweighed the losses. Taking in the risk of a protracted conflict, such a conflict that has now materialized, makes the whole endeavor look foolish in the extreme.

That is, unless a protracted conflict is actually a Russian win. Look at it from Putin's perspective. He was getting old and out-of-touch with the younger generations. People had started grumbling about the fact that Russia seemed to be going nowhere and had a generally bleak future. The organized opposition was firmly squashed, but this risked making unorganized opposition even more prevalent.

In such a situation taking a gamble on conquering Ukraine might not have looked so bad. A quick, successful toppling of the Ukrainian government would have looked like a major win and unleashed a wave of patriotic fervor that would have kept Putin buoyant for years. A less successful military operation and a subsequent low-intensity frozen conflict would still have created a useful siege mentality in the Russian population and a sense of crisis that would have translated into increased support for the leadership.

This kind of simmering low-intensity conflict is in fact something that Russia excels at. Such conflicts smolder in Moldova and Georgia without any solutions in sight. From a domestic political point of view this is probably highly intentional. The Russian leadership can portray the world, at least the world close to Russia, as a dangerously volatile place and the Russian population as very lucky to live in comparative tranquility.

Russia's behavior in Ukraine since 2014 sort of confirms this worldview. Why did Russia send its regular troops into Crimea in February 2014 and why did it foment an armed rebellion in Donbas later the same year? Both places were highly positive of Russia and it would not have required much diplomatic skill to make both regions peacefully secede from Ukraine and join Russia instead.

That is, if you want peace. Which might be the opposite of what Russia wants in its near-abroad. The real reason behind the Russian invasion of Ukraine might have been too much peace. Data from the OSCE monitoring mission in Ukraine sort of corroborates this. According to their last yearly report, 2021 was the most peaceful year in Donbas since the start of the conflict.

But who will win?

A frozen low-intensity conflict might have been one of Russia's desired outcomes. But it is definitely not high on the Ukrainian wish list. That is why Ukraine persists in executing large-scale offensives despite the costs in manpower and equipment. Russia probably did not even consider the possibility that Ukraine might win the war outright. This is still far from happening. That it is a possibility at all is a Ukrainian win of sorts.

The ongoing Ukrainian spring offensive (that turned out to be a summer offensive) did not get off to a great start. Reinforced by sophisticated Western armor, Ukraine felt strong enough, or was persuaded to feel strong enough, to risk a frontal assault on the Russian lines in Zaporizhzhia province. This turned out to be a costly mistake when at least twenty armored vehicles were destroyed or disabled outside Mala Tokmachka.

After this initial setback the Ukrainians fell back on a much more careful mode of advance. They send small groups of infantry into no-man's-land to clear mines and, crucially, draw fire from the Russian lines. This Russian fire can then be located and destroyed using accurate Ukrainian artillery fire.

This method of attack probably works. But it is slow and costly. It is also very similar to Russia's mode of attack in and around Bakhmut in the winter and spring. Russia eventually prevailed in Bakhmut but it took almost a year and cost the lives of tens of thousands of Russian soldiers. Ukraine can not sacrifice similar numbers of soldiers. The Russian defenders in Zaporizhzhia are also much better prepared than the Ukrainian defenders in Bakhmut were, making Ukraine's prospects look even dimmer.

What the Ukrainians do have is a grand strategy. Russia has a logistical weak spot in southern Ukraine. If the Ukrainians can reach the Sea of Azov and hold their ground they will have cut off the Russian forces to the west. Since Ukraine also has some quite fancy anti-ship missiles by now they will be able to practically shut down shipping in the Sea of Azov, including disabling the Kerch Bridge connecting Crimea to Russia.

By severing communications between Russia and Crimea and between Russia and the occupied parts of Kherson and Zaporizhzhia provinces, the Russian position in these areas will in practice become untenable. There will not even be much room for an ordered retreat, probably resulting in tens of thousands of Russian soldiers in Ukrainian captivity.

In a situation like this Russia might sue for peace. Most likely, that is what Ukraine is hoping for. Because after a successful southern offensive there is no feasible way forward for Ukraine. They can turn their troops east and attack the Russian-occupied lands there. But the going will be just as tough as in Zaporizhzhia and without any prospect of major strategic breakthroughs. The Russians will only slowly retreat back towards their own border inflicting grievous casualties on the Ukrainians in the process.

Unfortunately, I believe the negotiated settlement the Ukrainians are hoping for will not come to pass. Losing Crimea will be a body blow to Vladimir Putin, but he still has no reason to go for peace. If he settles for anything less than what Russia started with he will be seen as a loser and his days as president of Russia (and probably his days as a free or even a living man) will soon be over.

Probably the best Ukraine can hope for is some sort of coup in Russia that removes Putin and, in the best-case scenario, throws the armed forces into disarray. This is possible but not very likely. Putin might disappear, the Wagner rebellion showed his position is far from secure, but Russian society is currently very patriotic and not at all inclined to accept military defeats.

Since Ukrainian society is also currently very patriotic and even less inclined to accept anything that does not feel like military victory, the conflict will most probably roll on for several more years. This should probably be viewed as a Russian win, although it is very much a "win" rather than a win since it has in fact greatly weakened Russia's standing in the world and the quality of life of ordinary Russians.

The generational view

A general view is that there are only losers in war. A Russian "win" is in reality a loss. No matter what the result Ukraine will still have lost a tremendous number of lives, not to mention gigantic amounts of infrastructure and buildings. Surely there can be nothing positive about this, no matter who actually wins in the end.

In fact, it can. Ukraine has made significant gains even now, far from any battleground win. The loss of life and construction works in Ukraine is of course unfortunate. But the world consists of more than physical things. In the world of ideas Ukraine has made huge strides since the beginning of 2022.

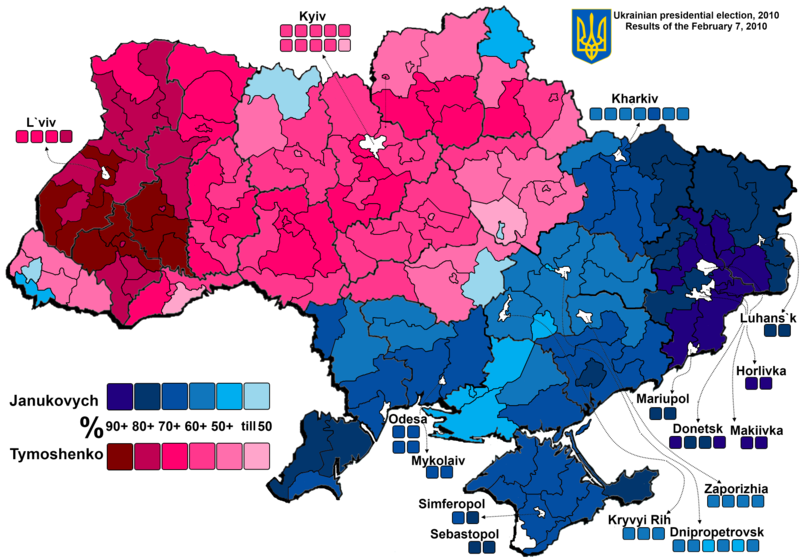

The map below shows the result in the second round of the Ukrainian presidential election of 2010, the last time all of Ukraine held a presidential election. As can be seen the Russian-friendly candidate Victor Janukovich was very popular in the east and south while the more Europe-friendly candidate Yulia Tymoshenko was more popular in the west and north.

In fact the difference is striking. In many parts of Donetsk and Luhansk provinces in the east Janukovich got 90% of the votes. Similarly, in parts of Lviv and Ivano-Frankivsk provinces in the west Tymoshenko received more than 90% of the votes. This was a highly polarized society. It is a small miracle that it functioned at all.

Ukraine was still a highly polarized society in the beginning of 2022. In the last parliamentary elections, in 2019, the second biggest party (with the strange name Opposition Platform - For Life) was openly arguing for an alliance with Russia and a rejection of all treaties with the EU.

This polarization largely disappeared when Russian tanks rolled in on 24 February 2022. It was an attack on the whole of Ukraine and nothing unites people as a common enemy. Even Opposition Platform - For Life condemned the invasion (although it took almost two weeks, presumably they needed to see if Russia would win outright first).

In Ukraine almost everyone speaks both Ukrainian and Russian. What you speak is to a large extent a matter of identification. Almost as soon as the first Russian missiles struck people who had previously spoken Russian in public started to speak Ukrainian. The Ukrainian president Vladimir Zelensky, a native Russian speaker who made his career as an actor in Russian language television shows, has not spoken Russian in public since the invasion started except for directly addressing people in Russia.

These things matter. A society needs some sort of overarching idea. Something for the population to unite around. Something that validates the cooperation of its people. Hitherto, Ukraine has lacked such an idea. The war with Russia has given them meaning and bridged the previously unbridgeable gap between east and west. This is Ukraine's liberation war, the war around which the national narrative will be spun.

No matter what size and what shape the state of Ukraine has after active hostilities cease, this newfound unity will be with Ukrainians for the foreseeable future. In this sense the war is a great win for Ukraine. For Russia, not known for its mastery of soft power, it is a great loss. And they probably have not even noticed it yet.

Greetings from Russia! Allow me to make corrections from the field.

Russian society does not look patriotic at all right now. Yes, there are no open protests -- because those who protest or even speak out against the government have been actively persecuted for 15 years at least. But there is no active support for the war either, as the few Russian pro-war enthusiasts constantly complain about.

Recently a Russian propaganda movie "Witness" was released about the preconditions of this war. The occupancy of the halls is practically zero, movie distributors put it on the most inconvenient sessions, because no one goes to see it. A total box office failure.

What a timely post! I was just wondering about the war. And your analysis - though it might of course have made some key mistake - is convincing. I recall reading years ago that Hitler would have rather not have rushed into war, but was terrified of losing support back home.

More interesting is the way militarism is itself a cultural difference. Many countries seldom involve themselves in military matters, while others are always fighting. I like a moderately peaceful stance - willing and able to fight, but regarding war as a situation of last resort, and actively pursuing other options.

> "Russians attacked Kiev using two trusts, one smaller from Belarus that moved on the western side of the river Dnieper, and one larger trust covering a greater distance from Russian territory to arrive at the Ukrainian capital from the east."

trust --> thrust

Your ancestors should really never have abandoned the voiceless dental fricative; it's a cool sound.