Mongols of North America

The Comanche carved a niche for themselves as the preeminent nomads of the North American prairie.

American history is usually divided into pre-Columbian and post-Columbian. This makes sense, considering the vast changes that the appearance of Europeans had on the continent. But it is a rough division and it misses at least some nuance in the transition period.

The advent of the Comanche empire is such a nuance. Of course, it was no empire in the classical sense of the word. The Comanche had no great cities or building works. They hardly even had a unified governance. Still, for a short period of time, they had that other trapping of empire: the ability to control their neighbors and in the process decide the political future of the North American interior.

A kingdom for a horse

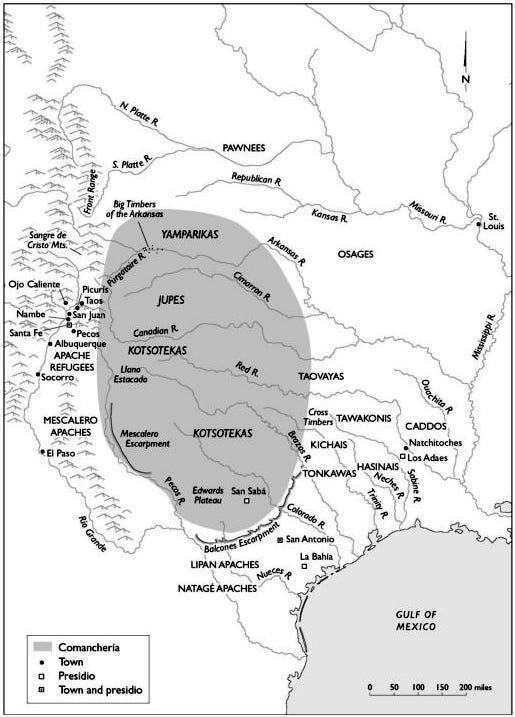

Comanche made their entrance in recorded history in the very first years of the 18th century. They were a small band, probably not more than a few hundreds, of hunter-gatherers from the Rocky Mountains who had now ventured down on the southern Great Plains and thus came to the attention of the Spanish authorities in New Mexico.

The Comanche were few and unremarkable. But they had arrived on the plains at an auspicious time, and they proved more than capable of taking advantage of it. The southern plains was of course well populated before the arrival of the Comanche. There were Wichitas, Kiowas and, above all, Apaches. These groups farmed land in the river valleys while also hunting bison on the surrounding prairie.

This traditional way of doing things was about to be upstaged by the Comanche. This was not so much the fault of the Comanche as a result of larger processes at play. South and west of the plains was the Spanish colony of New Mexico. Spanish explorers had arrived in New Mexico very early, lured by Aztec legends of golden cities. No golden cities were found but despite this setback the first Spanish colonies were established in New Mexico already in the beginning of the 17th century.

With the Spanish colonists came a new creature: the horse. Horses were useful for all sorts of things and spread rapidly in the Spanish colony. In 1680 Spain's native allies, the Pueblo people, rebelled and killed or expelled all Spanish colonists from New Mexico. The Spaniards would be back a few years later but one effect of this rebellion was that large numbers of horses were let loose on the plains where they thrived to such a degree that the prairie would soon be filled with feral horses.

The Comanche arrived on the prairie 20 years after the Pueblo rebellion, just as horses started to be widely available. Not burdened by any traditional way of living on the plains, the Comanche were able to immediately develop a new way of life. A new way of life on horseback, completely centered around the horse.

Post-Indo Europeans

The horse gave the Comanche mobility, they had probably always been nomads, as hunter-gatherers tend to be, but now they were very mobile nomads. But enhanced nomadism was not the main advantage of the horse. The horse made possible a whole new, and very, very profitable, type of economy. A type of economy that the Comanche were the first to exploit.

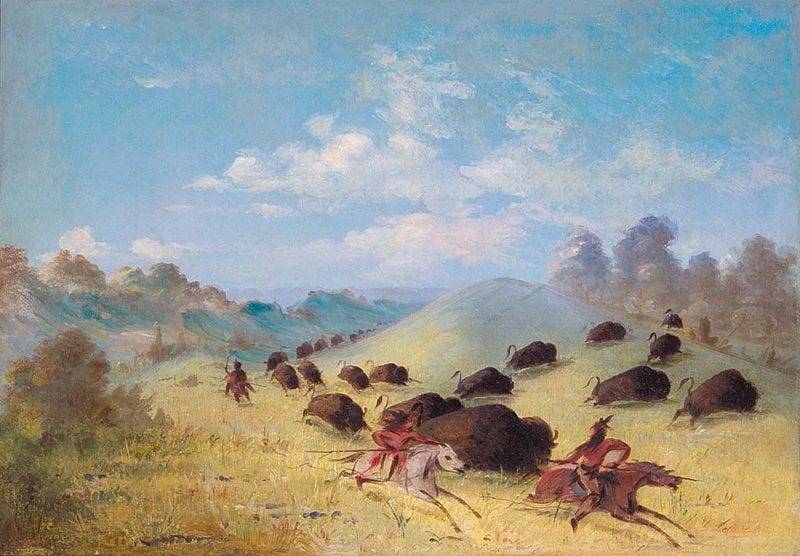

All previous inhabitants of the Great Plains had hunted bison. But they had hunted bison on foot which was difficult and dangerous. The new system the Comanches developed was done wholly from horseback. Bison are herd animals and when hunted they do not scatter but remain together. The Comanche found out that on their horses they could keep equal pace with the bison herds and using bows and lances they just picked off as many bison as they needed. This way a band of Comanche could kill hundreds of bison in a day, enough food to sustain a small tribe for several months.

Having found an extremely effective way of providing for themselves, Comanche used their plentiful spare time to subjugate their neighbors. Biological factors forced them to interact with their neighbors. As an extreme form of nomadic pastoralists their economy had severe shortcomings. Foremost of these was the fact that they only produced animal food making their diet dangerously protein heavy. They needed carbohydrates, which they could only get from the farming communities in the river valleys.

The plains can also be a harsh environment, especially in the winter, and the Comanche needed the river valleys with their woodlands and escarpments for protection against the elements. What developed was a classic example of nomad-sedentary co-existence. The nomad Comanche needed carbohydrates and crafted goods they could not make themselves. The villagers needed animal protein and the military protection that the nomads could offer.

Despite the mutual benefits, the exchange was very seldom equal. The Comanche had no reason to pay for what they could take for free. And took they did. In the first decades of the 18th century the southern plains were engulfed in almost constant warfare which saw the Comanche emerge as the hegemonic power. Thanks to their superior mobility, the Comanche could concentrate forces and defeat any foe, notwithstanding the fact that they started out with very low numbers.

The low number of Comanche would also be a transitory problem. Comanche turned out to be very inclusive. Their way of warfare was at the same time brutal and demographically sound. The typical Comanche attack was a large-scale raid on a lightly defended enemy village. Resisting warriors were slain, as were the old and infirm. The rest of the defeated villagers were enslaved. Children and females were incorporated into the Comanche tribe, the children could work and the females became concubines that could produce new Comanche warriors. Male slaves were sold on, or rather exchanged for tools and weapons, which ensured that the process could be repeated on yet more villages. The result was a demographic explosion. The few hundred Comanche that had started the 18th century had by mid-century transformed into a tribe with tens of thousands of members.

Lords of the southern plains

The Comanche success on the plains inevitably brought them into contact with the dominating European power in North America at the time, the Spanish empire. Comanche might have been expected to fear Spanish arms or at least respect the Spanish colonies for fear of losing access to essential European goods like guns and iron tools.

Both of these arguments were probably well-known by Comanche chiefs, but the Spanish colony of New Mexico had something even more alluring. The expansionist Comanche had an insatiable demand for horses. It was possible to trade horses for slaves. But the Comanche demand for horses was much greater than the Spanish demand for slaves. In fact, New Mexico's demand for slaves was quickly saturated once the Comanche started raiding their neighbors. Instead, New Mexico turned into a large exporter of slaves, most of which went to plantations on the Spanish island of Cuba.

When trade could not sate the demand for horses, the Comanche turned to raiding Spanish villages. The Spanish proved just as unable as their indigenous compatriots to resist Comanche raiding. The speed of horse-born raiding parties combined with the sparse and spread-out population made it practically impossible to withstand raids.

The colonial administration of New Mexico had only one response to Comanche raiding and that was punitive expeditions. A number of these were mounted in the early decades of Comanche expansionism, with lackluster results. Comanche nomads were generally too mobile to be pinned down by Spanish forces. As Comanche raiding continued New Mexico became so depleted of horses that punitive expeditions could no longer be organized.

The colonial administration instead turned to cooperation and appeasement. The Comanche were persuaded to stop their raiding in exchange for lavish gifts and promises of eternal friendship. In practice, the Spanish colonial government spared the Comanche the inconvenience of raiding and just gave them everything they wanted instead.

The Spanish still tried to control their troublesome neighbors by the type of gifts and trade they allowed. Gifts tended to be magnificent rather than practical and trade goods tended to be practical rather than martial. There was a strong ban on exporting guns and gunpowder to the natives and the export of horses was dissuaded, although mostly due to lack of horses in New Mexico.

For several reasons this was not a major problem for the Comanche. As for horses they really did not lack them anymore from the middle of the 18th century onwards. Horses thrived on the southern plains. In fact they were ubiquitous enough for wild horses to be collected and tamed. There was also a new Spanish colony called Texas which had perfect conditions for horse breeding and where the Comanche started raiding when the peace in New Mexico held.

Guns were another matter. The Comanche had no means of producing either them or the gunpowder they needed themselves. A Spanish embargo on them should have been devastating. In reality it was not, because the Comanche were able to find other suppliers. Foremost of these were the French traders that operated on the Mississippi river and its tributaries. When Spain took over French Louisiana in 1762 they had high hopes of finally stamping out the weapons trade with the Comanche. But by then it was too late. The Comanche continued trading with French smugglers and had also established links with English traders operating from Canada and American traders operating from across the Mississippi.

Shaping politics

For a hundred years, approximately between 1750 and 1850, the Comanche were a major force in North America. This was felt most keenly in New Mexico, Spain's northernmost outpost in America. During the 18th century New Mexico was complemented with Spanish colonies in Texas and California. Interestingly, these three colonies had very little interaction with each other. Texas and California were mostly supplied by sea while New Mexico retained its contact with the rest of New Spain through the 2400 km inland Chihuahua Trail.

Even though the Comanche had made peace with New Mexico they still continued raiding in Texas. In fact, their raids intensified after their deal with the New Mexican authorities. If New Mexico was their preferred trading depot, then Texas was their preferred raiding ground.

Comanche raiding had a profound effect on Texas during the first decades of the 19th century. Dispersed ranching was more or less impossible with the constant raiding and the population started leaving, if they were not killed outright. When independent Mexico emerged in 1821 the colony of Texas contained just 2000 Mexican subjects, less than half the number two decades earlier.

The Mexican government then made a fatal policy error. They opened the gates for immigration from the east. The United States had expanded west of the Mississippi river only a few years prior thanks to the 1803 Louisiana Purchase and now shared a border with Mexico. When the gates of this border swung open Anglo immigrants swarmed in.

The Mexican intention had been for the Anglos to act as a buffer and help defend against Comanche raiding. This was not what happened. The American immigrants were mostly southerners uninterested in ranching. They did not move into the interior of Texas as hoped, instead buying land along the Gulf coast where they ran cotton plantations and small-scale farming. The effect was that already in 1830 English-speakers significantly outnumbered Spanish-speakers in Texas but the Spanish-speakers still bore the brunt of Comanche attacks.

The inability of the central government to stem Comanche raiding contributed in no small part to the Texas secession of 1836. The government of independent Texas took a sterner view which led to all-out war with the Comanche. The Texans knew they had to take the fight into Comanche lands in order to win and equipped a number of ranger companies whose objective was to search the plains for Comanche bands and kill them all.

This genocidal warfare had some success but the Comanche retaliated with extensive raiding, all the way down to the Gulf coast. The result was a stalemate. In the end both sides realized they could not win the war and a peace was concluded in which the Comanche agreed to stay north of a demarcation line in return for gifts and other aid. In practice, Texas paid for the opportunity to cede away half its nominal territory. But Comanche raiding stopped.

Instead the Comanche took their raiding across the Rio Grande and into what is today northern Mexico. And not only northern Mexico. For a few years raiding reached such proportions that Comanche warriors came up to the outskirts of Mexico City. The whole of northern Mexico was laid waste, with benign support from the authorities in Texas and the Mexican province of New Mexico.

This extreme raiding demands an explanation. The primary objective of all Comanche raiding was horses and mules. These creatures were central to the entire Comanche economy. The Comanche were classic nomads and of course needed their horses for transportation. But they could supply their own horses through horse breeding, which they preferred to do, viewing horses bred by themselves to be superior to horses bred by Europeans.

The Mexican horses and mules were intended for trading. And the recipients of all these horses were primarily American farmers east of the Mississippi. In exchange the Comanche received all types of foodstuffs and industrial goods including guns and ammunition.

With their raiding the Comanche played a crucial role in American westward expansion. Not only did they provide hundreds of thousands of horses to American farmers and frontiersmen. They also did most of the heavy lifting in destabilizing the new country of Mexico, especially its northern parts.

When war broke out between Mexico and the United States in 1846 the American army could invade northern Mexico using established Comanche war paths. And often utilizing Comanche guides. Comanche raiding had already for several years severed New Mexico's communications with central Mexico leading to most of its trade going eastwards towards the US rather than southwards towards Mexico. The Comanche had ripened a fruit that fell easily into the lap of the American invaders.

No we khan

In the 1840s the Comanche were at the pinnacle of their power. They had brought Mexico to its knees and they were undisputed masters of the southern plains of North America. Yet, they never translated their significant military and economic power into any form of traditional political entity.

Had they made a go at state formation, their efforts had most probably been futile. Neither the Mexicans, nor the Americans, were inclined to accept any form of independent indigenous states. But it was also contrary to the Comanche way of life. Being true nomads it was not in their nature to submit to a centralizing power.

The main social unit in Comanche society was the band, or rancheria as the Spanish called them. This was a group of usually between 100-200 people living and traveling together. The limiting factor for Comanche groups, as with pastoralist groups all over the world, was access to pasture for their horses. A 100 person band could have over 1000 horses and these horses required large areas of pasture. A Comanche band usually only stayed a few days in a single spot before moving on in search of new grazing lands.

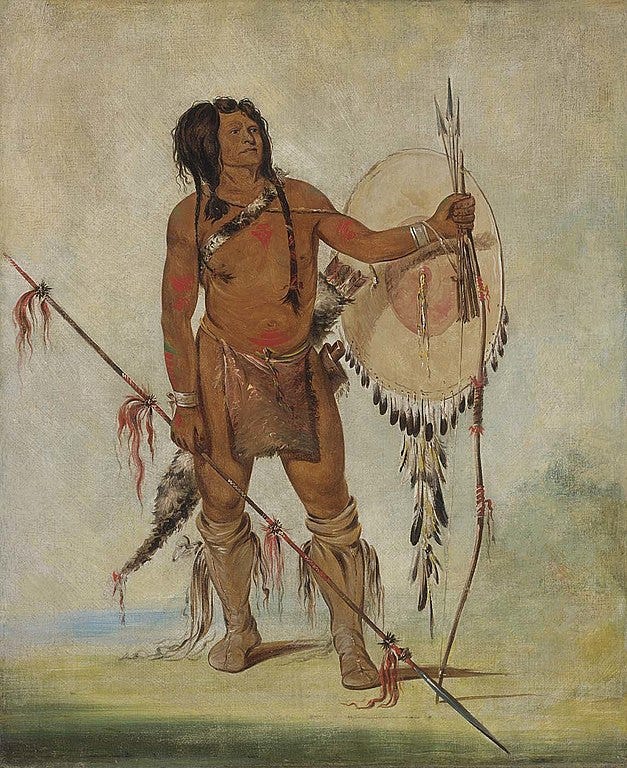

In theory all Comanche adult males were equal. In practice the band was led by a chieftain who was a wealthy older male. Wealth among the Comanche, as in all pastoral societies, was measured in heads of cattle, which for the Comanche meant horses. Horses were the primary capital of the Comanche, essential for the two mainstays of the economy: hunting and raiding.

A raiding expedition usually required 3-4 horses per warrior, one dedicated war horse and 2-3 traveling horses. Young warriors often did not have the required number of horses and instead rented suitable horses from older men in exchange for a part of the plunder. Young men were dependent on raiding since it was their only chance of accumulating horses of their own. Horses were not only required for raiding and hunting. They were also used to pay the bride price necessary to marry. A married warrior with a household of his own also needed more horses to transport his wife and children.

Apart from significant discrepancies in wealth, all Comanche men were equal. Women were another matter. Comanche women were usually viewed as the property of their fathers or husbands, not so different from slaves. And like slaves they were supposed to work hard. While Comanche men spent their time hunting and raiding, and preparing for hunting and raiding, it fell on the women to do the actual work of pitching and breaking camp, not to mention the very labor-intensive job of drying and curing meat and preparing and tanning hides.

Among the Comanche males decision making was in theory collective. In practice wealth discrepancies played an outsized role since Comanche custom demanded that a leader be magnanimous and generous and thus only rich men were in the running for leadership positions.

Despite living in small groups dispersed over wide areas the Comanche still had the ability for collective decision making. This was accomplished during the winter months when multiple bands descended on the same spots in the river valleys where thousands of Comanche could winter together. It was also possible for individual leaders of many bands to meet in council anytime of the year to quickly decide on important topics.

This flexible decision making was at its root dependent on quick transports, something that the Comanche were masters at. Despite moving over great areas, swift messengers could still call up a council in comparatively short time. In this manner the Comanche could act as one unit despite being nominally decentralized. They were perceived as, and acted as, one nation.

Tame west

Few could imagine it at the time, but the Mexican-American war turned out to be the last hurrah for the Comanche. Comanche society, and the Comanche economy, was very dependent on the bison. Comanche killed countless bison for sustenance. But they also killed countless more to trade. Even worse, they invited their allies, both other native tribes and New Mexicans, to hunt bison on their land as a sort of diplomatic gesture.

The bottom-line of all this was that a tremendous number of bison was killed each year. The number was also growing in line with Comanche expansion. The Comanche were expanding on the back of a finite resource. It was bound to come to a halt sooner or later.

Ultimately, this halt was surprisingly sudden. The 1830s and early 1840s had been unusually wet on the North American plains, leading to above average grass growth and thus to rich pasture for the bison. This long fertile spell probably exacerbated the problems since the Comanche could continue expanding without noticing any problems.

In 1845 began a drought period that was to last for 20 years. The first few years of the drought only affected the Comanche superficially. Partly because they coincided with the Mexican-American war but also because the Comanche continued hunting bison as before. With the not insignificant difference that the bison population could not recover like before.

Before the end of the 1840s many Comanche faced starvation. Epidemics of cholera and smallpox reduced population numbers, but available bison resources were even more reduced. With bison hunting in the doldrums the Comanche could only hope that the other mainstay of their economy, raiding, remained robust. But problems multiplied here as well. Despite being on the winning side of the Mexican-American war, Comanche found themselves cheated of their victory. Article 11 of the peace treaty demanded that the Americans shut the border to all cross-border raiding. The American border guards were never able to completely seal the border, but they made life difficult for the raiders.

Increasingly, Comanche turned to raiding north of the border, primarily in Texas. But here they met an aggressive and expansionist enemy, something else entirely than in their previous clashes in the 1830s. Texas grew explosively in the years following annexation. The population more than quadrupled between 1847 and 1860. The diminished Comanche bands could not do much against this human tide. Especially since the human tide could both put up US Army forts and organize militias to carry out punitive expeditions.

The Comanche were also pressed hard from the north. US policy aspired to place Indians in reservations and many tribes in the central plains accepted this. Some of these reservations were placed on land the Comanche regarded as theirs. Wars followed. And since the reservation Indians were given food and weapons from government Indian agents, the odds were not always in favor of the Comanche.

The American civil war gave a short respite. The US army was occupied in other arenas which gave the Comanche some leeway. But the real bonanza came after the civil war. Texas was then, as one of the Confederate states, regarded as hostile territory by the victorious Yankees. This meant that all Texas militias were disarmed. With the US army busy with occupation duties in the main population centers this gave the Comanche a free hand on the Texas frontier. For a few years in the second half of the 1860s northwestern Texas was picked clean by Comanche raiders.

This unrestricted raiding could not continue forever and pressure was mounting to get the Comanche into reservations as most other indigenous people had been forced to by this time. A Comanche reservation was also organized in Indian Territory (the future state of Oklahoma). The Comanche, being nomads at heart, mostly spurned the reservation. They visited in the winter to collect their government provisions but most of the year they roamed the prairie much as they had always done.

Exit on the back of a bison

The real deathblow for the Comanche came in 1873. That was the year when commercial buffalo hunters first appeared on the southern plains. Advancements in hide processing had made buffalo hides attractive for industrial processing. New railroads also connected the plains to the industrial centers in the east. The result was a "buffalo rush" in which professional hunters did their utmost to kill as many buffaloes as possible, usually only taking the skin and leaving the rest of the carcass to rot.

The Comanche were aghast at this attack on their livelihood and they made attempts to fight back. At the Second Battle of Adobe Walls at least 700 Comanche warriors attacked a camp of 28 buffalo hunters. But progress had outrun the Comanche. Despite their crushing numerical superiority they could not defeat their enemies. The hunters were equipped with modern long range rifles and could shoot at the attacking Comanche from a much greater distance than the attackers. There were further clashes between Comanche bands and army patrols but the Comanche could not prevent the bison becoming practically extinct.

The loss of the bison was a decisive blow to the economy of the Comanche. Despite the introduction of some cattle pastoralism after the 1840s, the Comanche society was still very dependent on bison hunting. More than economic, bison had significant social and even religious connotations in the minds of the Comanche. A Comanche without bison was like a fish without water. The end of the bison was in practice the end of the plains Indians.

In 1875 the last band of free-roaming Comanche limped back to their reservation in Indian Territory. Without bison they faced starvation on the plains and government handouts in the reservation was their sole means of sustenance. All remnants of the Comanche nation were henceforth relegated to the reservation. And it was a remnant. There had been tens of thousands of Comanche in the late 18th century. In the census of 1890 there were only 1,598 left.

This article is wholly based on a book called The Comanche Empire by Pekka Hämäläinen (that is a very Finnish-sounding name and, yes, he is from Finland although he is nowadays professor at the University of Oxford).

I think Anders really did us a favor here, because Pekka Hämäläinen's book is both long (about 500 pages) and, in my opinion, a bit difficult to read. I tried to read it, but gave it up because of repeated remarks about how prejudiced it is to assume that it was self-evident that the European colonists would win the struggle over America. I believe it actually is self-evident that the more technically and social complex society will eventually win, if it ever decides to spend enough resources. But until those more complex societies get interested and unified enough, being small and mobile is a great military strategy that can allow technologically and rather socially primitive societies to dominate more complex societies.

Very Interesting.

I wonder if you could make article on Navajos, who managed to grow at same time by relying on sheep.