Hexagonal cities

The Romans were city building masters of the Ancient world. They knew how to build orderly and well-functioning cities. Their basic premise was to build a square grid of streets, or at least as much square grid as the local topography allowed. From this basic structure the city could grow more or less infinitely simply by adding more blocks to the city grid.

This Roman approach to city planning has more or less stayed the same over the last 2000 years. Cities of the Middle Ages had notoriously narrow and winding streets but the Middle Ages were also famed for its weak governance making their city planning, or rather its lack of overarching city planning, something of an outlier. For most of urban history, including the present day, the square grid has been the rule.

City buzz

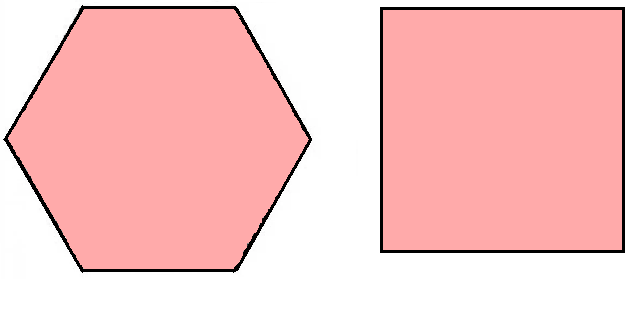

A square grid is simple and easy to understand. But it is not very efficient at maximizing the built up area compared to the area of streets. Most people know that the most efficient way of building a latticework is by hexagons. The beehive is the most famous example where evolution has bequeathed the bees with a storage system that maximizes the enclosed volume but minimizes the amount of wax needed to make the walls.

Hexagonal street grids are not a new invention. According to an article from 2000 in Journal of Urban Design (available as a PDF here) urban planners have been pondering hexagonal forms in city planning since at least the 19th century. During the first decades of the 20th century interest in the idea seems to have been continuous.

This theoretical interest, however, was never translated into any practical projects. As far as I can google not a single example of a hexagonal street grid has ever been built. Instead the square grid reigns supreme. The early 20th century proponents of hexagons were in many cases persuaded by another novelty, the cul-de-sac, a dead-end street ending in the center of a city block. The cul-de-sac promised better utilization of streets, just as hexagonal street plans, but without the downsides.

In praise of squareness

While hexagonal street grids have a certain mathematical charm they also have some drawbacks. For one, navigation in a hexagonal city is difficult. How would you even name the streets in a hexagonal street plan? Would each little side of every hexagon block have its own name? And how do you give directions in a street grid where everything looks the same but nothing is really straight?

It is not only directions that are more difficult in a street grid where the streets turn every few hundred meters. It is nigh impossible to put the pedal to the metal if there are no straight streets. Even though red lights have a tendency to limit traffic speeds even in square grids, the constant 60 degree turns in a hexagonal street grid will almost certainly lead to even lower speeds, something that will limit connectivity for everyone in the city.

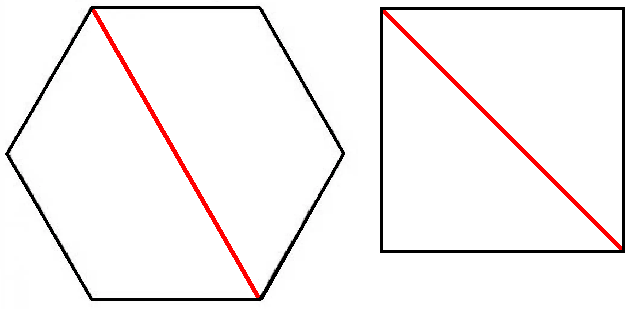

Then there is the problem of buildings. One good reason for rectangular city blocks is that buildings are almost always rectangular. There is logic to that. Most people want their rooms with right angles and their furniture with straight sides. But there is a mathematical explanation to this desire as well. A rectangle can always be divided into smaller rectangles. A hexagon cannot be divided only into hexagons. You will always need other shapes, mostly triangles, to fill out the gaps.

Finally, while hexagons are very parsimonious with boundaries, this frugality comes at the price of straight line traveling. The natural example is an intercity railway which has to be laid down in a straight line in order to minimize the travel length. This straight line will inevitably wreak havoc with any hexagonal street plan. And the problem is not limited to railways. Ordinary highways and a host of other utilities will also want to travel to their destinations in a straight line.

Up on six

With disadvantages like these, no wonder that hexagonal cities have never been built. But in fact most of the criticisms listed above can be rebutted, or at least deflected.

The problem of navigation is a real one, but the problem is just as real in every Medieval European city lacking a square grid. Most people living in, and visiting, these cities do not seem to mind the navigational problems but instead think they add to their “charm”. Also, navigation is sort of a 20th century problem. Today everyone has a GPS and follows its instructions slavishly.

There is no doubt that rectangular buildings are easier to build and to live in. But a hexagonal street plan can quite easily accommodate rectangular buildings. In a typical hexagonal block most plots of land will be rectangular and only a minority, those in the corners, will have non-rectangular features. This is an inconvenience, but hardly a fatal one. Besides, corner plots are usually the most sought after in a block and those who get them will probably make do.

The straight line problem is more difficult to solve. A railway going its own way will inevitably wreck the hexagonal plan and adaptations will have to be made to make it work. On the other hand, this is almost always the case even with a square grid. It is only rarely that exceptional objects, like railways, are arranged in the exact same angle as the street grid. If it is not the square grid has to accommodate straight line objects running counter to the grid, just as the hexagonal city.

Aces up your street

Hexagonal street grids also have some advantages all of their own. The lack of straight lines might be detrimental to navigation but it is very beneficial to the local climate. Traditional square grid cities can get very windy when the air is channeled into the straight canyons created by the main streets, a street canyon effect is created. Streets that turn 60 degrees at every corner do not have that problem.

Another positive is traffic safety. In a square grid there are lots of four-way intersections, where there are multiple possibilities for accidents, especially involving left-turning traffic. In a hexagonal grid there are no four-way crossings, only three-way intersections with much reduced possibilities for collisions.

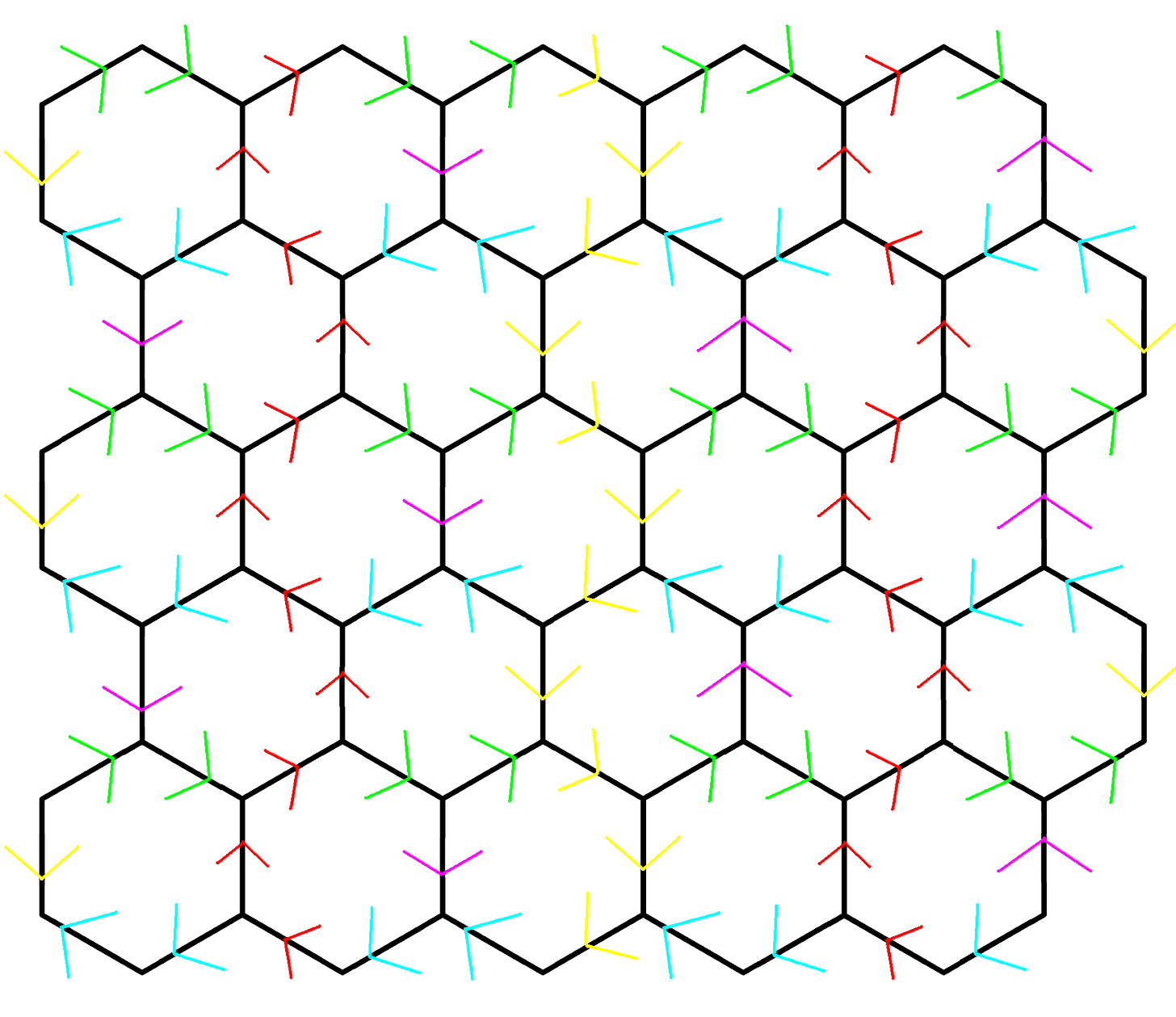

In fact, it is perfectly possible to make a hexagonal street grid with only one-way streets, as in the very nice graphic below which I have made myself in Microsoft Paint. In such a street arrangement there are no intersections whatsoever, which would make motor traffic very safe indeed. It is of course less efficient in terms of distance traveled to the average destination. But as can be seen from the image it is possible to make “avenues” in both the vertical and the horizontal direction where the one-way traffic is going continuously in one direction.

Doing the math

The main reason for building a hexagonal city is that it is area efficient. But how efficient is it? The answer is that it depends. This StackExchange topic delves into it in some depth, although it is perfectly possible to do the calculations oneself.

The main variable is the size of the blocks. In a comparison between square and hexagonal grids where the area of the blocks is identical, the hexagonal grid will require 7% less street length.

But equal area might not be the best constant for a comparison. The size of a city block is mostly dependent on the distance to the street. A fairer comparison could therefore be the diameter of the block, the length across the block at its longest. If we make this measurement equal for the square and the hexagon the hexagon block suddenly has an area 30% larger than the square block. It also gives the hexagon grid 23% more block area per unit of street length compared to the square grid. Or, looked at from the other side, 18% less street to build for every unit of built-up area.

Mental construction site

Having to build 18% fewer streets might sound impressive. But in fact the cost of building and maintaining streets is piddling compared to most other costs of urban living. Even if we add other types of utilities to the calculation the total savings would still be limited and probably not reason enough to start building cities totally differently from today.

The equation would change if we could put the land value of the extra built-up area on the pro side. Since there are urban areas where land values are truly astronomical this could be a big deal. However, these areas with high land values almost always have high land values because of city planning rather than despite of city planning. It is not really the land itself that is valuable but rather the ambient city planning that channels traffic and hence people and services to specific areas. These areas then get immensely valuable.

Hexagonal cities are bad at channeling things to a central location. In fact, part of the charm with hexagonal grids is that they slow things down and cut distances. In a true hexagonal grid no one part of the city is better connected than any other part. This is good for small-scale self-sustaining-neighborhood type of cities but not really well suited to the good-communications-with-bustling-center type, the one with prices going through the roof.

The high land values making a hexagonal city seem attractive in the first place are thus likely to be destroyed by the very same hexagonal city. There is also the fact that in really expensive cities land values are only part of the story. Sky values are just as important, the limiting factor is not a lack of land as much as a lack of free sky to get daylight in, something that can be solved without a brand new street grid. In New York and other high-value cities there is a brisk trade in air rights meaning that the excess area from having square grid streets instead of hexagonal grid streets is put to some use after all.

For these reasons the prospects for the hexagonal grid look bleak. After all, the concept has been known for a long time and yet no hexagonal cities have been built. Hexagonal cities also have some difficult impediments to tackle. One is that it is not really possible to build one hexagonal block. Trying to press one hexagonal block into an otherwise square street grid would not only look silly, it would be prohibitively expensive. To come into its own a hexagonal grid would need to be big, preferably big in the sense of a whole city.

There is only a very limited number of brand new cities being built around the world. The chances of any of these choosing a never before tested street plan for its general outlay is not very high. However, it should be possible to build lesser areas in totally new styles. A quite large, semi-dense residential area on pristine land seems the most promising candidate.

The likelihood of actually seeing a hexagonal city in the real remains slim. In fact it is worse than that. Urban romantics have real problems just imagining a hexagonal city. In the classic city building computer game Sim City the aim of the player is to build their own city and make it as big and beautiful as possible. That is, as beautiful as a 90 degree angle allows it to be. The square grid is built into the game engine and suckers for six sides do not need to bother.

The strength of the hexagonal plan lies in its disadvantages. Ideally one uses hexagons for small residential neighborhoods where the additional bits and corners are filled with greenery; there, the winding streets discourage speeding, and embrace foot traffic entirely within their surrounds. Long, straight streets provide little insulation from major streets, and make for depressing neighborhood walks.

My favorite plan has hexagons with two small plots of land to a side, creating clusters of twelve-family neighborhoods with a communal garden and playground where children can play together. If neighbors can be enticed to share even more, the plots can be made even smaller at three per side, and the communal area can contain the kitchen, showers, a library, and of course the local rohrpost stop. The focus here is on intimate and efficient neighborhoods rather than straight and efficient streets, encouraging neighbors to interact once in a while rather than living lonely and insular urban lives. If people don't need to go anywhere, who cares if the streets aren't straight?