Everybody wants a piece of Marc Andreessen

As the tech sector gets increasingly productive compared to the rest, people will be more and more interested in plundering it and less and less interested in doing something productive themselves.

For two years, I have tried to write a post about why AI development will not lead to unemployment or even shorter working hours. I have consistently failed. Then I stumbled upon Marc Andreessen’s Substack.

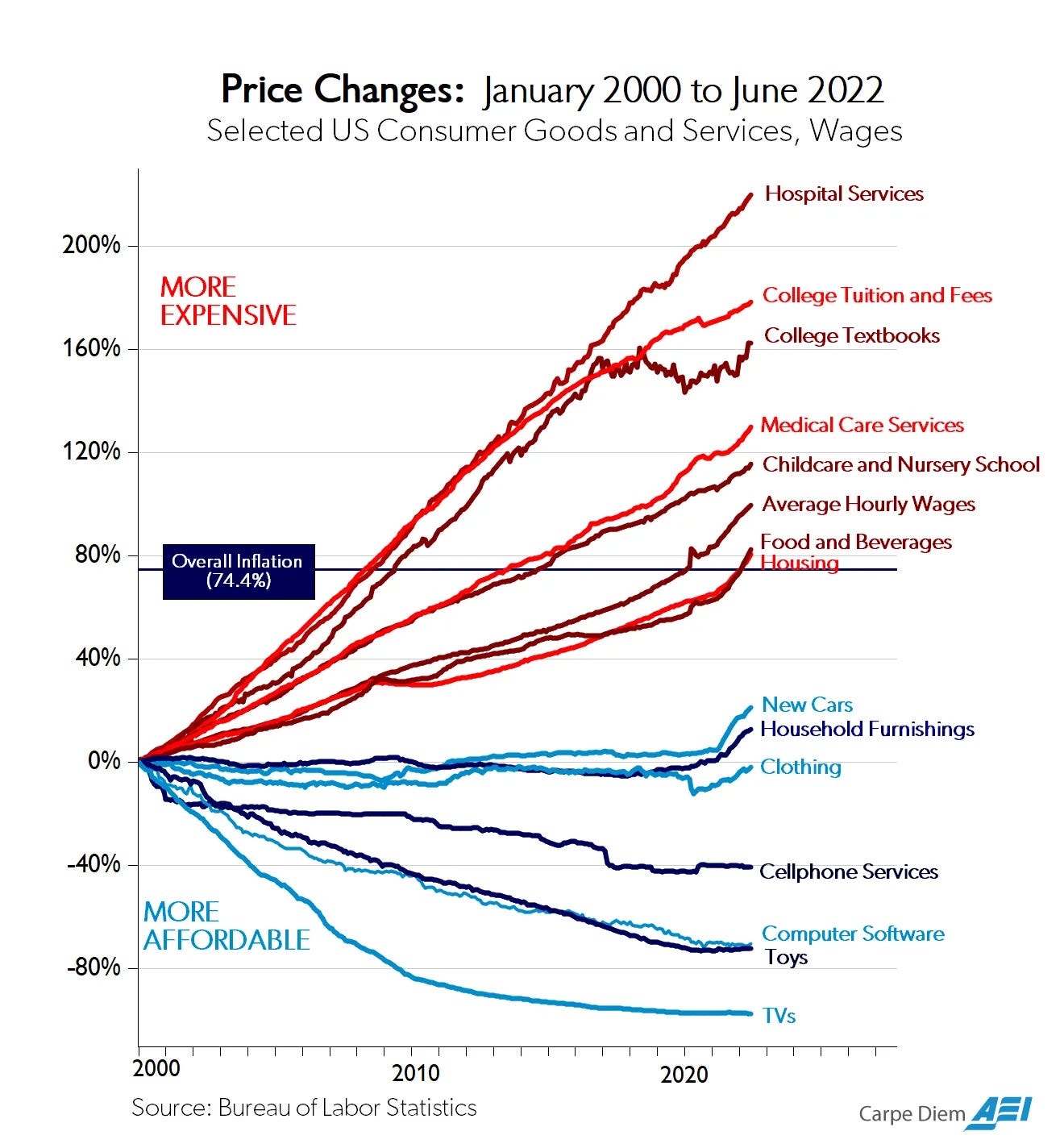

There it was: The idea I have tried and failed to express, under the title Why AI Won't Cause Unemployment. Since Marc Andreessen's explanation is better than all my unpublished attempts together, I will quote most of his post, including its red and blue diagram:

“This chart shows price changes, adjusted for inflation, across a dozen major sectors of the economy.

As you can see, we actually live in two different economies.

The lines in blue are the sectors where technological innovation is allowed to push down prices while increasing quality. The lines in red are the sectors where technological innovation is not permitted to push down prices; in fact, the prices of education, health care, and housing as well as anything provided or controlled by the government are going to the moon, even as those sectors are technologically stagnant.

We are heading into a world where a flat screen TV that covers your entire wall costs $100, and a four year college degree costs $1 million, and nobody has anything even resembling a proposal on how to systemically fix this.

Why? The sectors in red are heavily regulated and controlled and bottlenecked by the government and by those industries themselves.[...] The regulated sectors continuously grow as a percentage of GDP; the less regulated sectors shrink. At the limit, 99% of the economy will be the regulated, non-technological sectors, which is precisely where we are headed.”

Someone detail-minded could point out that the red line sectors are not only heavily regulated: They are also local, while industrial production is global. But that misses the point: Local economic activities are regulated because they can be regulated. In a follow-up post, Marc Andreessen explains that these regulations, in fact, constitute a hidden universal basic income scheme for the people employed because of them:

“We already have Universal Basic Income, it’s for all the people in the red line sectors (not their fault, but it’s true). Every time you buy any of the red line items, you’re paying for it. In the future, that will be virtually everyone.”

So, basically, the rest of society is exploiting its most productive sectors. A small part of all workers produce things that consumers and companies actually want and need. Those workers are taxed on most of what they produce. Either they are taxed directly. Or they are taxed through laws that force them to pay hordes of unproductive people for “services”. The productive people also need to employ people, for example lawyers, who help them get around regulations in order to get things done.

This is an ongoing, continuous development that has existed as long as society has existed in its modern form. The otherwise brilliant economist John Maynard Keynes failed to see it. He predicted that his grandchildren would only work for 15 hours a week.

Keynes just looked at the productivity development of the day and concluded that after some decades it would take much less time to produce the necessities of life. He somehow assumed that as soon as people had reached a certain level of material comfort, they would just live and let live.

Why did he assume that? Such a thing hasn't happened at any time, at any place ever. Throughout human history, whenever there has been a surplus of production, there has been people fighting and arguing over that surplus. In the Stone Age, women produced and men fought over the right to tax them and impregnate them (simplified statement). In the Middle Ages, peasants produced and warriors and priests fought and argued over their surplus.

The welfare state is the modern heir of those warriors and priests. Citizens discuss what is morally right and then form laws that direct a substantial part of the surplus of production to those rightful causes.

The issues in fashion differ. Sometimes public discourse favors the end of poverty. Sometimes it favors food safety or medical safety. Sometimes it favors the environment. Sometimes it favors help for the disabled. Sometimes it favors better construction norms.

Every time a new political trend starts, a new set of workers will be added: Care workers, teachers and inspectors to make sure that this certain thing stops going wrong. New laws are created, and with them people are employed to uphold those laws. After a few years, political questions tend to change. Some other problem will be the most important problem of the day. New laws will be made, new positions will be created to uphold those new laws.

What happens to the laws and employees of the previously trending issue? Are their positions abolished? Only if they are unwise enough to make such a big fuss that their abolition becomes the new political question of the day. That seldom happens. Most commonly, they are just added to the general bureaucratic load of society. The employees appointed and their successors will silently add new, more careful rules to their area of expertise. They are all convinced those additional rules are justified, because surely their area of expertise is one of the most important of them all. And lawmakers and the public will accept those new rules, because they are proposed by experts.

With time, society gets loaded with regulations. Many of those regulations do not even have public support. They are just there as a left-over of an issue that was once trendy but is now largely forgotten.

Loaded

Marc Andreessen's Substack made me feel a rare level of intellectual affinity. That surprised me, given how different lives he and I live. But thinking about it, Marc and I actually have one thing in common: We are both trying to do something. While he is changing the world as an inventor and investor, I'm building a house for my family. And we are both meeting stifling regulations that hold back opportunities we are seeing.

In The Techno-Optimist Manifesto, Marc Andreessen writes:

“We believe that if we make both intelligence and energy “too cheap to meter”, the ultimate result will be that all physical goods become as cheap as pencils. Pencils are actually quite technologically complex and difficult to manufacture, and yet nobody gets mad if you borrow a pencil and fail to return it. We should make the same true of all physical goods.”

As a tech bro and risk capitalist, Marc Andreessen naturally sees this from the producer point of view. As parents with limited finances, Anders and I see it from the consumer point-of-view. A number of years, we decided to take advantage of the superb technology around us and build a new house. We figured that combining the windfall of rising productivity with a little know-how, we and our children could live in the kind of house that only the upper class could live in a few decades ago. Although we are not rich or even well-off, we have been able to save money to buy industrial products like big windows, sheet metal roofing, a number of different power tools and even a small sawmill to make our own lumber.

As we have been building our house, we have become aware that society (in our case, Swedish society) isn't too eager to allow us to freely use this affluence with which industry provides us. Although we are building our house in the plain countryside where it is not visible from any other house or any public road, there are still a number of laws standing in the way of our plans. In 2009, a law was made that all big windows need to be made from safety glass. That effectively doubled the price of windows. Then there are the laws that say that every roof, also a glass roof, needs to tolerate two meters of snow (we rarely have a tenth as much snow here), that a wheelchair must be able to turn around in the bathroom and navigate the entire kitchen, that there must be a sink next to the stovetop, that there must be a bedroom on the ground floor and there needs to be a wardrobe in the bedroom…

Not one, but two persons are supervising us throughout the process. For some reason, our inspectors care especially about our indoor painting. In general, the Swedes are a docile bunch that meekly accept that the government organizes their lives. But not even the Swedes understand why people aren't allowed to live in houses with unpainted interiors. Every time I tell someone here around that we are very busy painting the interior of our house and putting every floor list in place because otherwise the authorities will not allow us to live in our house, I get the same reaction: “But why?!”

No one loves a bureaucrat

Marc Andreessen also asks that question:

““But… why do we put up with this?”

I don’t know, why do you?”

The simple and boring answer is that no one knows which rules, inspectors and bureaucracy are actually necessary. Some of them doubtlessly are. I can in no way claim that all inspectors and other politically motivated people are unnecessary. It is not like everyone who works in production is doing something good and everyone who inspects production is there to put obstacles in their way. For example, if someone emits toxic chemicals while making useful things, the inspector who stops it will be the hero.

Every society needs politics, administration and policing of some sorts. Advanced production depends on advanced social organization. And there can be no advanced social organization without people who uphold, safeguard and develop it.

The tricky question is how many and what kind of people are needed. Where does the essential task of holding society together end and where does fluff and overregulation begin? Which people are honestly trying to build a better society, and which people are most of all after a good position for themselves?

This has always been a problem. A number of people have always been seeking to lead and police others instead of producing themselves. Some of them have been essential for society. Some have been unnecessary and some have been actively harmful.

Class society upended

The only thing that is new is the proportions between producers and exploiters (of the benevolent and malevolent kind). As long as sustaining a human being took many man-hours per year, most people had to spend most of their time doing productive work. That was a law of nature.

Most human societies have consisted of a warrior elite and a more or less oppressed population of workers. In very simple societies, adult men tend to constitute the warrior elite and women and children constitute the working class (although depending on the environment, adult men work more or less too). In more advanced societies there are classes containing both sexes. Until the industrial revolution, the upper class was always a warrior class, with merchants and manufacturers only holding an intermediate position.

As I wrote in my post Capitalism put an end to systematic warfare, the rise of capitalism profoundly changed this order. In high-tech societies, waging war is a collective effort in which clever engineers and diligent factory workers are just as important as brave warriors. For the first time in history, producers could rid themselves of their exploitative warrior protectors. Instead, the task of defense, administration and ideological leadership was spread widely over society.

This victory of producers over warriors boosted technology development to marvelous levels. To such marvelous levels that it has upheaved the ancient natural law that most members of every society need to spend most of their time working. High-tech society opens for an entirely new social structure: A structure where a majority of extractors is exploiting a minority of producers.

I think what we are seeing today is the return of the exploitative upper class. This time it doesn't come as a minority, but as the majority.

The principle is simple. Wherever there has been a natural resource and people working it, those people have attracted warriors. The warriors have forced “protection” on the workers in return for a share of their products. As long as conditions are tolerable, the workers have incentives to cooperate with their protectors, because there are always even nastier people out there, threatening their very existence.

The 20th century constituted a brief pause from this law of nature. Technology was efficient enough that for most people, working in the productive sector made more economic sense than stealing the result of other people's work. At the same time, technology was inefficient enough that it actually needed a lot of human hands and minds to operate. Going to the factory, doing manual labor in synchrony with a machine and forming a trade union to demand decent conditions was the most efficient way of increasing one's standard of living.

Now the demand for unskilled or semi-skilled workers is decreasing. As machines are getting better and more complicated, fewer people are capable of working with them. Instead, a new natural resource is taking form: The tech sector. The tech sector consists of a few very skilled workers who create enormous value. They understand the most advanced technology and can thereby leverage it. They can make great productivity improvements for us all.

Like all natural resources, those skilled workers attract a lot of attention. They are like a Shangri-la in the middle of an ordinary landscape. Sure, the rest of us can work with what resources and skills we have. But will it pay off? Or will it pay off better to compete for a share of the great productivity of the tech sector? The more technology develops, and the fewer people who master the developing technology, the bigger the incentives for the rest of people to spend their days thinking of creative ways of forcing some of the surplus off the tech sector instead of trying to produce something on their own.

That way, we are getting a new class society, with a majority of warriors and a minority of workers. I can't see any way of escaping this situation. Tech workers might try to break loose under strong protectors, like island states, to escape the masses of their own people and the regulations they spend their days making up. But they might also find it easier to pay the tribute the majority demands. Especially if that tribute can be simplified into a universal basic income.

Just paying my construction inspector to do nothing would be much better for me than paying him to dictate how and when I should decorate the interior of my house. I expect tech bros to reason similarly. If you have the choice of being taxed and regulated or just being taxed, most people would opt for the latter.

In The Techno-Optimist Manifesto, Marc Andreessen argues against a Universal Basic Income on the grounds that humans are made to be productive. I agree. But what to do when humans are not productive after all? Then paying us for doing no harm might be the better option.

This is an interesting post and Wood from Eden is in general a great substack.

This resonated with me a lot, since my country is currently in turmoil over many issues, one of which is that there is a class of ultra-religious people who do not work and do not participate in society in any constructive way, but still receive considerable subsidies from the government, as they are in the ruling coalition.

So here the situation is much worse than “The simple and boring answer is that no one knows which rules, inspectors and bureaucracy are actually necessary”. Every reasonable person (and even economists ;) ) know that having a large part of the population that doesn't participate in the work-force and is not educated in basic STEM subjects but still receives a large part of the pie is untenable and unreasonable. But political power enables this new "warrior class" to take its unjust share of the spoils in any case.

So I'm less optimistic about UBI. I think that when most people get UBI but are still the powerful majority, they will want more than the Basic. I think they'll want an increasing share of the pie, to the point where it will seriously hurt production.

That's what happened with many of the warrior classes, did it not? The peasants were squeezed to the last drop and when the first drought or flood arrived, the whole economy collapsed and many died. This has happened many times.

So I suppose just "paying them off" would not be enough to stave off the collapse for long. Either we need to find a way to make more of the society productive, or we need to somehow ensure that the majority of the population doesn't enact self-serving laws (which means minority-rule and is probably very problematic from a human-rights angle).

I sure hope that I'm mistaken, though :(