An uncivil civil war

Civil war is in the air. Why not revisit one that has already taken place?

Not so long ago I watched a film about an imaginary American civil war not that imaginatively named Civil War. The film depicted a Trump-ish president being forcefully removed from office by an unlikely coalition of Texas and California. However, the film was heavy on the plight of war correspondents and very light on the political maneuvering that must have led to the state of civil war, which made the whole film quite pointless to me.

Hollywood films seldom get made in a vacuum. Which means that civil war is in the air. Of course, having a presidential candidate with a proven track record of disputing election results makes the risk of conflict a tad more likely. But the greater problem is undoubtedly the increasing polarization of American society.

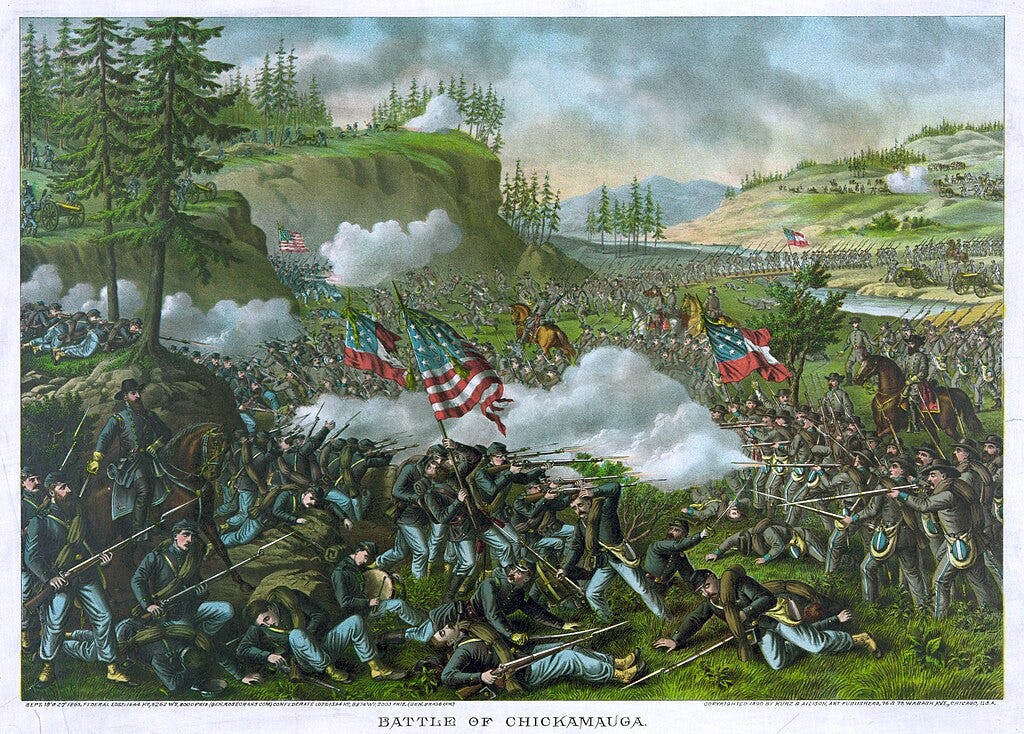

Americans might believe they know a thing or two about civil wars. After all, they have had their own, very famous, such war. This is most probably a mistake. An eventual future civil war will almost certainly have very little in common with the American Civil War of the 1860s.

The main difference is that the classic American civil war had a neat geographical component. Although there was a somewhat messy borderland the belligerents were confined to the south and north respectively. The difference between Yankees and Dixies were substantial enough to almost give the war an ethnic component. In this it was very similar to the great majority of civil wars that have been fought along ethnic lines.

But it is a poor guide to an eventual future civil war that will be fought along political or even ideological lines. In fact, history is not that rich in political civil wars fought in states with modern, non-corrupt bureaucracies. There is one, however: the Finnish civil war of 1918, which I just happen to know a little about.

A Swedish introduction to Finland

Finland used to be an integral part of the Kingdom of Sweden. Since before written history, the Swedes of what is today east-central Sweden had more contacts with the Finns across the Baltic Sea than they had with the Geats and Danes of what is today southern Sweden. For good reason, in those days it was significantly easier to travel by boat (or sled in the winter) across the archipelago to Finland than it was to travel by horse or foot across deep forests to southern Scandinavia.

This state of affairs might have continued until today, if not for the big bad Russians that dwell in the east of Europe. From around 1700 the expansionist Russians piece by piece pried away the Finnish lands from the king of Sweden until, in 1809, it was all gone.

This was probably the best thing that could have happened to both Sweden and Finland. The 19th century was a time of national awakening, had Finland been a part of Sweden then it would surely have demanded independence, which would have been denied or at least delayed, resulting in conflict, perhaps even violent conflict.

Instead, Finland was accepted into the Russian Empire as an independent grand duchy under the tsar. Finland was allowed to keep its internal politics, meaning that administratively speaking, Finland is a carbon copy of Sweden, since they were one and the same until the Russian conquest.

On the coat-tails of the Great War

During the Russian occupation Finland, for the first time, developed a uniquely Finnish national character. During the Swedish regime, Finland was considered just another part of Sweden, albeit one where the peasants spoke a strange language. Now came Finnicization, where the previously Swedish-speaking urban intelligentsia switched to speaking Finnish, and at the same time developed a Finnish literary language, a Finnish bureaucracy and a Finnish national history (sometimes, confusingly, written in Swedish).

Thanks to the Russian victory in 1809 all of this newfound nationalism was directed at the Russian occupiers instead of the previous Swedish overlords. Both Finnish-speakers and Swedish-speakers in Finland could rally around the common cause of being against the tsar.

For a long time the Russian authorities were surprisingly lenient. During practically all of the 19th century, Finland was as good as independent in internal matters. This might have had something to do with Finland's closeness to the then Russian capital of St. Petersburg. Finland, being decidedly European, was regarded as something of a playground for the tsar and the Russian upper nobility, who all had summer houses in the Finnish archipelago.

In the early 20th century this started to change. Russia aspired to become a more normal European country instead of the feudal state of old, and this entailed closer governing of peripheral provinces like Finland. The Finns resisted, of course, mostly peacefully but sometimes violently, as when the Russian governor-general Nikolay Bobrikov was assassinated by a Finnish nationalist.

Then came the Great War. Nominally, this hardly affected Finland at all. Russia was at war from the Baltic to the Caucasus against Germany, Austria and Turkey. But Finns did not fight because, as a quasi-independent grand duchy under the tsar, they were exempt from the general Russian conscription. The war hardly affected the economy either. Finland traded mainly with Russia and its main foreign trading partners were the Scandinavian countries, neutral and still open to trade. War created demand and Finland's economy was booming.

Yet, the war sharpened tensions. Tens of thousands of new Russian troops moved into Finland in order to defend it from a hypothetical German sea-borne invasion. While Finns did not have to fight themselves, a constant barrage of war news made them sort of used to the concept of war. Some Finns no doubt felt jealousy towards other nationalities in Eastern Europe who, at that very moment, were fighting for their freedom and independence.

And then, in 1917, Russia disappeared. The Russian February Revolution (which took place in March) got rid of the tsar and the Russian October Revolution (which took place in November) got rid of most of everything else. Suddenly, and quite unexpectedly, Finland was free from the Russian yoke.

This is the final struggle

In the early 20th century Finland was one of the world's most democratic places. Not only did they have universal suffrage, they also had women's suffrage which Finland, according to some metrics, was first in the world to introduce.

Despite its democracy, or maybe due to it, Finland was also rife with internal conflict. As everywhere else during the first decades of the 20th century the conflict was between the lower classes, the workers, and the upper classes, the gentlemen. The partitioning of society was a bit more complicated than that but basically it was about the working class, which included everyone that considered themselves working class, against everyone else.

And the Finnish working class was no pushover, led by the Social Democratic Party of Finland; they were easily the strongest political force in the country. Urban factory workers were the core of the working class, but by no means all the working class. Tenant farmers, which made up a majority of the rural population in many places, were reliable social democrats. As were many types of artisans, craftsmen and domestic servants.

Given Finland's unusually democratic constitution this gave the Finnish social democrats an unusually strong political position. In the parliamentary election of 1916 the social democrats received their own majority, meaning they could form their very own government, the world's first socialist government (albeit still subordinated to the Russian tsar).

The non-socialist opposition was, naturally, not thrilled about the outcome. But this being during the Great War the situation was fluid and provided opportunities. In the summer of 1917, when Russia was in chaos, the conservatives persuaded the social democrats to support an autonomy law which was a minor step towards independence. The Russian government in Petrograd was predictably enraged. It ordered the dissolution of the Finnish parliament, something that the tsar had the right to do according to the constitution then in force.

In this legal gray area the social democrats had probably expected the nationalist opposition to refuse orders from the temporary government in Petrograd. After all, they were heavily nationalist and were not supposed to take orders from Russia if they could avoid it.

But tactics trumped theory and the non-socialist parties willingly suspended parliament forcing new elections. In these new elections in October 1917 all the other parties ganged up on the social democrats, who, as the governing party, was also blamed for the chaotic situation in the country. The result was that the social democrats lost their majority and were relegated to a much diminished role in opposition.

The fall from power, and especially the quasi-treasonous way in which it was accomplished, enraged large segments of the working class. The general mood was that the parliamentary system was stacked against them and that the powers that be would never let the working class rule the country.

Constructing a war machine

1917 was a tumultuous year in most of the world. Despite not being an active participant in the war, Finland was very much affected by the general mood. The revolution in Russia contributed to disorder in Finland. Finland at the time had no army and although the police was made up of Finns it was led by Russians and distrusted by the independent-minded population. After the Russian revolution in March large demonstrations and public meetings were held and Russian police commanders were forced to resign (including the Russian governor-general). The Finnish police did not cease to exist, but it was very much diminished as a general force.

The situation was not helped by the fact that the Russian revolution had made a mess of the Finnish economy. Russia was by far Finland's largest trading partner and chaos in the Russian economy quickly spilled over into Finland, especially as Finland was heavily dependent on food imports from Russia. The worsening economic situation led to unemployment and food shortages, which in turn led to strikes and general unrest.

In this unstable situation the trade unions started to organize guard units, bands of young men whose job it was to maintain order during strikes and demonstrations. The non-socialist segments of society did not trust the workers' guards one bit and soon started setting up their own paramilitary forces, the protection corps.

In the beginning all of these units were local in nature and unarmed. This changed gradually during 1917. National organizations were set up and a progressively more desperate search for weapons begun. Finland was not devoid of weapons. Shooting clubs were popular and there were plenty of hunting rifles in the countryside. However, these weapons were mostly in the hands of the middle and upper classes and the workers' guards had to rely on ever more violent expropriations to get their hands on them.

World revolution enters the fray

In this already combustible mix came the Bolshevik coup in Petrograd on 7 November 1917. In Finland, both socialists and non-socialists, looked on in amazement as the Russian working class, or at least its self-appointed dictators, took power. The bourgeoisie was horrified but the Finnish socialists were electrified. If the Russian working class could take power, surely their brothers and sisters in Finland could do the same, where the workers were both more numerous and better organized.

The leadership of the Social Democratic Party were not as thrilled. They had a conservative bent and were also heavily invested in the parliamentary system. But by this stage this did not matter very much. The Finnish workers were not led by the Social Democratic Party as much as by the trade unions and, especially, the workers' guards.

Radical trade unionists and guard members immediately started setting up worker's councils modeled on the Russian soviets. The trade unions also called a general strike which lasted from 14 to 20 November. Its aim was to show the power of the working classes and maybe force some sort of political change. This was only six weeks after the parliamentary elections that large parts of the Social Democratic party viewed as illegitimate and demand for some sort of non-parliamentary solution to the parliamentary situation was high among the working classes.

Already by this time everything was set up for civil war. The ideological lines were clear and both sides had the organization for actual warfare. The next few months were characterized by escalating confrontations, often involving firearms. Both sides made concentrated efforts to arm themselves. The workers' guards received weapons from their ideological brethren the Bolsheviks, while the protection corps received a large shipment of arms and munitions from Germany.

There was no single force strong enough to stop the march towards war. The leadership of the Social Democratic Party tried to rein in the young hotheads in the workers' guards, but this only resulted in a formal break between guards and party. From now on it was the workers' guards that called the shots.

Another party with no power and no intention to stop the drift towards war was Russia. The Bolsheviks had their hands full consolidating their own power. In fact, it was Bolshevik strategy to let as many peripheral parts of the empire go (content in the conviction that the forthcoming world revolution would soon return them to the fold). The Finnish government used this to formally declare independence on 6 December 1917.

All sides of Finnish society viewed independence positively. But it did nothing to solve the fundamental conflicts. On the contrary, December and January saw increasing clashes between workers' guards, by this time usually called the Red Guard, and the protection corps, which would soon be known as the White Guard. Both red and white guards were now better armed and the clashes usually involved firearms and regularly led to fatalities.

The general problem was that the newly independent nation lacked force. Finland at the beginning of 1918 had no armed forces and only a weak and discredited police force. On 25 January 1918 the non-socialist government decided to solve this problem in the worst possible way, by declaring the protection corps to be the legitimate armed forces of Finland. Obviously, the red guards did not accept that their mortal enemies were now the law of the land. On 26 January the workers of Helsinki placed a red lantern in the tower of the Helsinki Workers' House, signaling that they did not subordinate themselves to the legal government. The Finnish civil war had begun.

Finn against Finn

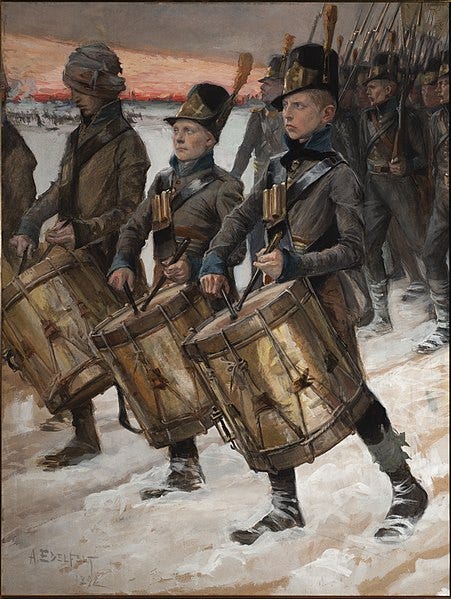

The Russian Grand Duchy of Finland had no armed forces of its own. This did not mean that there were no soldiers in Finland at independence. Basically, there were two types of soldiers. One was the officers of the Imperial Russian Army. Although Finland lacked conscription and no Finn had to fight for Russia there was always the option of becoming a career soldier in the tsar's forces.

In 1917 around 400 Finnish citizens served as officers in the Imperial Russian Army. The Bolshevik coup forced most of these officers to return to Finland, although the trip was both long and hazardous for many of them. These Russian-Finnish officers were to become the leadership during the civil war. Since they were predominantly upper class they almost exclusively joined the white side. Examples can be telling. At the outbreak of civil war the white guard was led by former Russian general Carl Gustaf Mannerheim while the red guard was led by former Russian lieutenant Ali Altonen (who had not been a lieutenant since 1906).

But the Imperial Russian Army was not the only source of experienced soldiers. There were also the Jägers. Jäger (meaning hunter in German) was a type of infantry in the Imperial German Army. Almost from the beginning of the Great War in 1914, anti-Russian Finnish nationalists had slipped over the border to Germany to join the German armed forces in their war against Russia.

These Finnish refugees became quite numerous as the war dragged on. The Germans organized them into several Finnish Jäger companies and let them fight on the Eastern front against Russia. In January 1918 there were around 2000 Finnish Jägers in German service. When it was clear that Finland was heading for civil war Germany released around 1500 of these Jägers (the remaining 500 were deemed politically unreliable and remained in German service) and shipped them to Finland. The Jägers were experienced soldiers and were to form the backbone of the white army during the war.

The red guards had no corresponding sources of experienced soldiers. They did, however, have high morale and legions of willing volunteers. Before and directly after the declaration of war the reds raised an army of 100,000 guardsmen (including about 2,000 guardswomen). Most red guards were willing fighters although many also joined for material reasons, poverty bordering on starvation was the norm for the Finnish working class in the winter of 1917/18 and guardsmen at least got to eat.

There were also a great number of soldiers that did not fight. Namely the Russian soldiers stationed in Finland. These numbered around 60,000 in January 1918. At the time Russia was still formally at war with the Central Powers and a German invasion could not be ruled out. Most Russian soldiers, however, just wanted to go home, and most did during the spring of 1918. A few thousand Russian soldiers joined the red guard out of ideological conviction. A battalion of Polish soldiers originally conscripted into the Russian army joined the white guard out of anti-Russian sentiment.

In general, the Russian soldiers did not take an active part in the hostilities. They were still important because they provided the arms needed for warfare. Both the red and the white side tried to seize as much Russian arms as possible. In this quest the white side proved much more successful. Mostly because the reds tried to convince the Russians to hand over their weapons while the whites demanded it. And their demands carried weight since they represented the legal government of independent Finland, an independence that the Russian government had acknowledged. The fact that the white side had access to hundreds of former Russian officers no doubt helped too.

Report from a war

The actual warfare, when it started, was short, although very intense. Both sides used the first few weeks of the conflict to consolidate their position. The red side controlled all the major cities, which gave them a strong position in the south, but they still needed to take active control of the countryside in between. The white side initially controlled most of the countryside, including all of the north of the country. The only exception was a few industrial cities in the north, chief among them Oulu where the local red guard hopelessly outnumbered the local white guard. The whites sent reinforcement there and conquered it at the beginning of February.

The first real strategic maneuvering was a red offensive northwards. The reds controlled the majority of the Finnish population and at the start of the conflict the red guards were numerically superior to the white guards. The reds felt confident enough to try to take over areas they did not initially control. Their offensive, however, exposed their weaknesses in leadership and organization and although some local attacks were successful the general offensive quickly fizzled out.

Instead the whites started advancing, strengthened by an inflow of experienced Jägers from Germany and a general conscription in white-controlled areas. They quickly arrived at the south-central city of Tampere, Finland's third city, its foremost industrial center and a stronghold of the red guards. The Battle of Tampere was fought over three weeks from the middle of March to early April. The whites were victorious and since the reds had spent all their best forces the war was in practice over.

The red situation was not helped by the fact that on 3 April Germany had entered the war by landing an infantry division outside Helsinki and was marching on the capital. Helsinki fell on 13 April (the Germans made liberal use of artillery, in a war that otherwise relied heavily on small arms, which is why the above mentioned worker's house was destroyed) and red refugees streamed eastwards towards what they believed was safety in the Soviet Union.

Despite not having an army when the war started, the fighting spirit the Finns would be famed for during World War II was still very much present. Most obviously in the fierce battles they fought against each other, especially in Tampere, where fighting was vicious and often to the bitter end. The Germans also got a taste of this. When attacking Helsinki the German command sent a smaller detachment east to cut off the retreat of the fleeing reds. 400 German soldiers set up defensive lines in the small village of Syrjäntaka. These soldiers, veterans of the Eastern Front, were probably a bit surprised when the column of red refugees was not stopped by their machine gun equipped lines but instead smashed right through them (albeit at a high cost).

To the victors, the right to spoil

The Finnish civil war was short but intense. Total combat deaths were in the vicinity of 10,000 people, of which around a third on the white side and two thirds on the red side. Finland at the time had around three million inhabitants.

But combat deaths were far from the only cause of death during this time. The fighting was vicious but the end of the fighting was brutal. The chaotic months before the formal start of the war had set the tone, killings and revenge killings were the norm and the soon-to-be combatants were desensitized from the start.

At the start of the conflict the reds took over swathes of the most populous areas. Directly after the takeover a wave of score settling commenced. Factory owners, large farmers and others who had in some way offended their workers were forced to go into hiding or were otherwise assaulted or even murdered. A few hundred white civilians were killed this way, including a couple of moderate social democrats who had made themselves unpopular among the radical sections of the working class.

But the red atrocities paled in comparison to the white terror. From early in the hostilities the whites adopted a policy of killing all enemies, whether hostile or not. When the whites swept over red areas later in the spring, summary executions became the norm. A staggering 10,000 reds or suspected reds were executed this way.

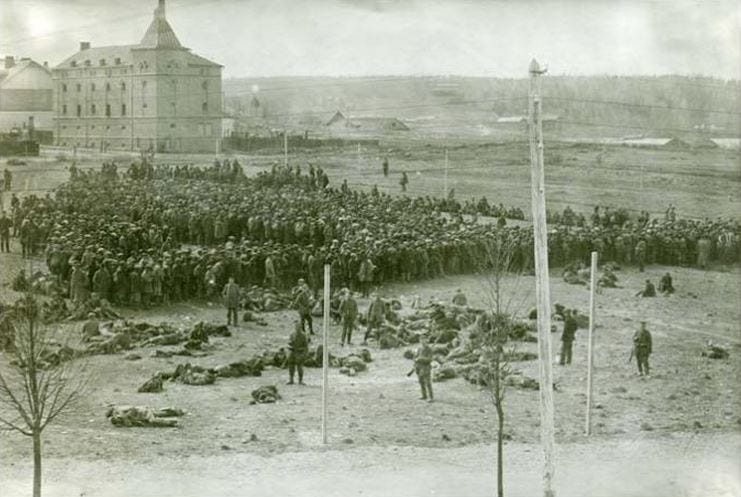

And it did not end with executions. Almost 100,000 red guards, trade unionists and social democrats were locked up in concentration camps after the war. This was a deliberate attempt to quash working class Finland. When parliament assembled again after the war there was only one social democrat present, of 92 social democratic parliamentarians. The other 91 were dead, in hiding or locked up in concentration camps.

The camps were temporary but extremely deadly. Most concentration camps were only active for a few months over the summer of 1918. Yet 12,000-14,000 prisoners died of disease, starvation and the occasional execution. This was not necessarily a deliberate strategy. Finland in the summer of 1918 was starving and the victorious whites had no intention of wasting precious foodstuffs on their vanquished foes in the concentration camps. The result was apocalyptic scenes and mass deaths.

All in all approximately 40,000 people died civil war related deaths during eight months in 1918. That is, well over 1% of the Finnish population perished in the conflict. The deaths were concentrated among young working class men. Thousands of Finnish reds also fled to the Soviet Union after the conflict. Many of these would be executed in Stalin's Great Purge in the 1930s.

And yet, Finland prevails

Almost the most surprising thing about the Finnish Civil War is that despite the mortal animosity between red and white a unified Finnish society remained after the war. The Social Democratic Party was temporarily stymied in the aftermath of the war. But only temporarily. It would continue winning elections throughout the 1920s and 30s and formed a government (albeit short-lived) as soon as 1926.

A crucial factor in returning the country to normality was, ironically (and tragically), the many executions. These once and for all defanged the radical labor movement, removing the threat of a communist takeover in the eyes of the bourgeoisie. With the threat gone, the feeling of mortal fear disappeared and left space for other, more constructive, feelings.

Chief among these was remorse. During the summer of 1918 Finnish (white) society gradually realized what they had done. And they, at least the law-abiding majority, did not like it. The violent excesses of the civil war also presented legal problems since warfare is hard to accommodate within the law. The solution was a blanket amnesty that went into force already in September. With the amnesty both sides were pardoned: The reds for their armed insurrection against the legal government and the whites for their genocidal execution while putting down the insurrection. All concentration camps were quickly closed and most prisoners released.

This did not mean that all conflict in Finnish society disappeared. The fight over the narrative was very much alive. Most visibly represented by the name of the war. While red sympathizers (and most of the rest of the world) called it the Finnish Civil War, the white sympathizers, including official Finland, called it the War of Independence, pretending that it was a war against Russian imperialism rather than against its own citizens.

Throughout the 1920s and 30s there also persisted major strands of political extremism in Finland. Even though many radical workers had been killed or fled to the Soviet Union some remained in Finland. The communist party of Finland, which was the natural home of these radicals, had been banned meaning that extremists on the left had to work underground.

Far worse than the radical left was the radical right. These consisted of the right-wing elements of the white guards and their sympathizers. In the immediate aftermath of the civil war their energies were mostly concentrated in the Greater Finland movement. Later on they were organized in the Lapua Movement, which was an anti-communist and de facto fascist organization. Not believing in democracy, they worked outside of the party system until, in 1932, they tried to pull off a March on Rome style coup. They had misjudged their support, however, and official Finland moved in with force, banning the Lapua Movement and arresting all its leaders.

It would take another war to finally unite Finnish society. When Russia attacked in 1939 white and red Finns all rallied to its defense. Finland's ultimate loss in the war also helped. Among the Russian demands were political changes in Finland like the disbandment of the white guards (which had been retained after the civil war) and the legalization of the communist party. These changes had been necessary for a normalization of Finnish society and since they were forced upon Finland from the outside they caused no resentment within the country.

Can it happen again?

History may be fun. But can we learn anything from it? Unfortunately, not much. Things that happened in the past are usually too steeped in circumstances of that particular time and place to be of much use in a modern setting. If there is any lesson to be drawn from the Finnish Civil War it is that civil wars, real civil wars, are very unusual. They need exceptional circumstances to take place, such circumstances that almost never happen.

What is a real civil war? As I tried to convey in the introduction, the vast majority of all civil wars are not civil wars as much as regular wars that just happen to be fought within the borders of a state. The belligerents are two geographically, socially and usually ethnically separated entities that fight a war between them. The American Civil War very much fits this description although Yankees and Dixies were quite similar in ethnic terms.

The Finns, at least the white Finns, tried very hard to make the war into a national war by painting it in ethnic terms. During the war, and even more after the war, they tried to portray it as a war against the Russian oppressor. Russian prisoners of war were almost without exception executed immediately. This policy had no exceptions, even the highest ranking Russian national on the red side, Georgy Bulatsel, was executed in the aftermath of the Battle of Tampere. Bulatsel was a Russian nobleman, a lieutenant colonel in the Imperial Russian Army and some of the officers on the white side must have known him personally. None of this made any difference when compared to the need to paint the war in ethnic colors.

The white attempts to give the war a veneer of ethnic conflict was of course deliberate. The whites knew that Finns might hesitate to kill other Finns. By pointing out the otherness of the enemy they increased their own unity. In-group and out-group are very important concepts during a war and ethnic differences make perfect divisions between groups. By painting the enemy as Russian strangers instead of Finnish neighbors they decreased sympathy for the enemy and increased cohesion on their own side.

Politics by other means

Political conviction is usually not strong enough to make people risk fighting, and dying, for. The Finnish Civil War is special because people actually fought, and died, for a cause that was at its core political. For this to happen two criteria had to be met: People felt compelled to fight their neighbors and there was no power able to stop them from fighting their neighbors.

Both the red and the white side in the Finnish Civil War were desperate. The reds were desperate because their poverty was such that they were actually starving. The whites were desperate because they were mortally afraid that the Bolshevik coup taking place just across the border in Russia would spread to Finland. Both sides felt they had their backs against the wall and had to fight their way out.

But Finland in early 1918 was also special because there was a power vacuum. A functioning state, with a functioning monopoly on violence, would have used its power to declare a winner in the conflict without actual warfare. The war would then have been fought in parliament or perhaps in the courts (the whites would have won) and the state's power would then have forced the outcome upon the losing side. Newly independent Finland had no army and only a weak police force and therefore no one knew where real power actually lay. The two sides had to fight a war to determine that.

Nothing of this applies to America of today. Americans might be agitated, but they are not desperate. American political indignation is easy to dismiss as hyperbole. While many Americans are passionate about the right to bear arms at all times or the right to have an effortless abortion it is very unlikely that Americans are willing to die for these rather obscure issues. It does not really compare to being executed or seeing your children starve. To suggest that 10 million Americans would risk death by joining a rebel militia, like the Finnish reds did in 1918, for any contemporary political issue is unlikely to say the least.

And even if they did there is nothing close to a power vacuum in modern America. American police forces might be politicized and therefore unreliable. But the US armed forces are not only the world's strongest, they are also unified and apolitical. Even if 10 million Americans joined a rebel militia the US Army would have no problems sweeping them aside to uphold the constitutional order.

The bottom line is that while it might be good politics to talk about civil war in America, the risk of such an outcome is minimal. Americans might be polarized but they are still too mixed up with each other to risk violent conflict. A much more likely outcome is that, given a few more generations of geographical sorting, different parts of America will have grown so different from each other that the American state simply falls apart in geographically distinct sub-states. But that day is still far off. For the moment we will have to make do with civil acrimony rather than civil war.

I am shocked by the characterization of American bureaucracies as non-corrupt.

I know little about the Finnish Civil War, but I know about contemporary America and the American Civil War.

1. While the Confederate states were all situated in one compact geographic area, there was often considerable internal dissent within those states (and in the North) as to whether to support the Confederacy vs. the Union. In particular, in the South, it was hillbillies vs. planters and planter wannabes.

The hillbillies rarely owned slaves (they couldn't afford them, and the Appalachian terrain didn't lend itself to large-scale plantation agriculture) and considered the government on far-off Washington to be less likely to intrude on them than the government in the state capital.

In the case of contemporary America, take, for example, Illinois. Illinois is considered a Team D state for purposes of national and statewide elections, but that is because so many people live in Chicago and environs. Once you leave Chicago, most of the rest of the state is pretty red. A similar pattern can be seen in other states. Basically, the big cities and areas with large black or native populations (Latinos, less and less) are Democrat strongholds. Everything else is Republicans.

https://images.app.goo.gl/nT6GWS1xSSNsnuih9

You can spot the Rez in the west and upper midwest using this map.

2. The US military, at the general officer level is far from apolitical, although serving generals rarely openly engage in politics.

https://www.usnews.com/opinion/articles/2024-09-23/why-former-u-s-military-leaders-endorsed-kamala-harris

That said, the US military heavily recruits from minorities (who are looking for a bus ticket out of whatever hell they come from) and rednecks (who actually buy into the Eagle Flag Freedom bullshit). During the American Civil War, the standing army was quite small, but the officer class in particular was disproportionately Southern.

And keep in mind, in many red states, pretty much every male over the age of about ten owns firearms and there are LOTS of combat veterans.