AI images litter the internet

Creating a picture of one's own mind can have a value. But reality has a value too.

Now I am going to make enemies with most of my blogging colleagues. Because wherever I go, I see AI generated images. The technology has only existed for a couple of years. And still, it seems like almost everyone uses it. Then it must be great, right?

I suggest it is not-that-great. Every time I take a closer look at a picture and realize it is an AI image, I feel stupid. When looking closely, I have been asking myself questions like Why does the woman in the picture have no face? Why does the child look like an animal? How can there be so many ducks in the same place? How can people farm on such a steep slope? When I realize that I have been staring at an AI image, I immediately answer myself: Because the AI made the picture like that, stupid!

No one intended to make a picture with a faceless woman and a child with a snout or a field that looks like a lawn. Searching for meaning and intention in the details of an AI image is about as intelligent as searching for deeper meaning in a stained wallpaper. It is visual gibberish.

Gibberish can indeed sound good. It is not necessarily unpleasant when someone sings “la la la”. And visual gibberish can look good. There are many images out there with the only purpose to create a pleasant ambience. Advertisement pictures. Wallpaper, for that matter. Everybody knows that the wallpaper is there only to provide a pleasant-feeling background. A person who zooms in on the flowers and leaves and geometrical patterns of a wallpaper is considered a fool lacking any meaningful life. It is the same with AI images. They are understood to be strictly superficial. Whoever takes a closer look is a fool who should have better things to do.

Unreal for real

This implicit superficiality is not only negative. As long as cameras have existed, there has been a business of creating images that look real, but are not-quite-real. There was, and still is, a professional category of people who diet, work out, get operated on and painted in order to look too good to be true in a photo.

I wouldn't be sad at all if these people get replaced by computer-generated images. When I was young in the 1990s, there was a debate on altered images of photo models that gave young girls unrealistic expectations of how they should look. All the better then if people learn that pictures of beautiful people are too unreal to be worth looking at.

I will also not miss genre images created with photo models. As far as I'm concerned, that typical Getty Images photo of a “family of four” or “teenager and mother arguing” doesn't have to be a photo of real people. No one believes such a photo carries any documentary value or deeper meaning anyway.

Reveal the world

Genre photos were never super fun. They were also not much of a problem, because they were so expensive to make that only big newspapers and companies with advertising budgets could afford to use them. Now such images are suddenly free to make. That way, they are turning up everywhere, replacing another category of images: Photos of real people and real places.

When people had to use photos or drawings to please the eye, they were forced to reveal something about the world: A photo shows how a certain phenomenon looked, at a certain time. A drawing indicates what a person thought at a certain time, and their ability to transmit that thought to a paper.

It is often nothing special. It is just something worth being a little bit curious about. AI images punish curiosity. It is like they grin “ha ha, no meaningful information here!” in the face of everyone who looks closer. Even if there is not a lot of information in real-world photos and drawings, there is some information. And that makes all the difference. It makes the images a possible ground for discovery.

In defense of reality

When Anders and I started blogging, we had no comprehensive strategy for how to find pictures for our texts. Since we both use Wikipedia extensively it came naturally that we used Wikimedia Commons a lot. I have more and more come to appreciate the time I spend searching for pictures. Looking at images teaches me new things.

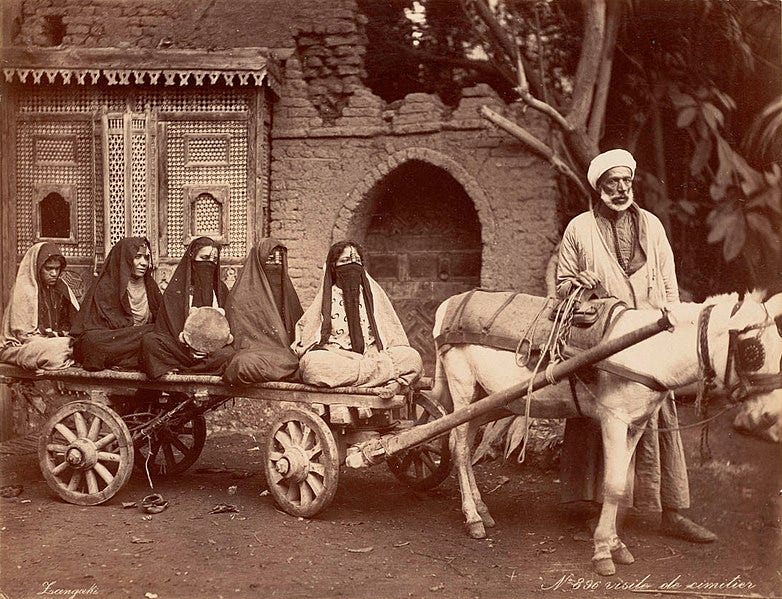

Images from reality can be interesting for many reasons. One is realism. Like this photo, which I used as an illustration to my post The origins of patriarchy:

Such an image is immensely more valuable if it is real than if it is AI generated.

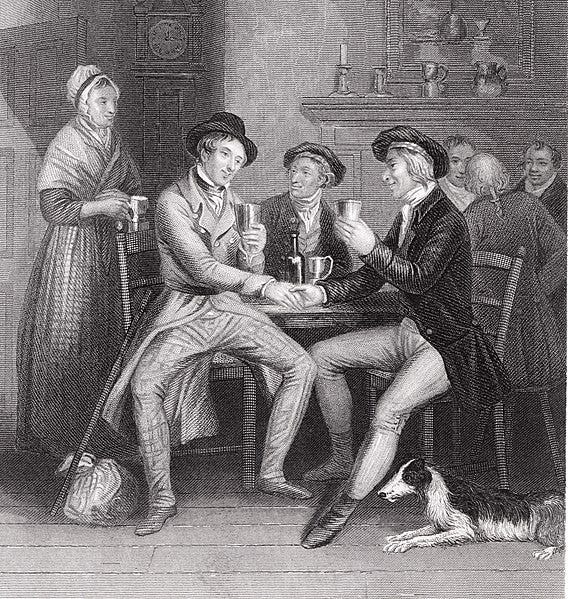

Images can also be interesting for what they say about human psychology and human artistic capabilities. This illustration to Auld Lang Syne, from the 1840s, is one of my favorites.

Illustration to Robert Burns' poem Auld Lang Syne by J.M. Wright and Edward Scriven, about 1841, Wikimedia Commons

Technically, that drawing is far from perfect. The sitting man on the left looks as if he is sitting in the air rather than on a chair. Also, people's facial expressions are a bit goofy. The two men in the front look more “in love” than “good friends” according to today's standards.

All those things taught me something new. Nothing of it is definitive, but it gave me suggestions for further thought. I would say that after having seen this not-at-all-famous drawing, I know a tiny bit more about the 19th century. I would prefer to know much more about the illustration, the people who made it and their time than I do. But I'm better off knowing that the illustration exists than having never seen it.

Imaginary beings are also part of human psychological reality. While I feel stupid every time I find myself closely studying an AI image, I have no qualms against casually studying a picture of my favorite imaginary being, Lightning McQueen. Lightning and his peers are works of art. Someone has experimented with detail after detail in order to create the most perfect anthropomorphic cars. If I take a close look at Lightning and his friends, I will see the result of those minds working. Could be worth a few seconds of my time.

My admiration of Lightning and his colleagues reveals one thing about me: I'm not actually against AI art. Images of beings like Lightning is just what AI-driven image generators can produce. Lightning was born in 2006, so he very likely came about through a team of human illustrators trying out design after design until the movie bosses were satisfied with the result. If such illustrators are assisted by AI technology by now, I don't mind at all. What matters to me, as a consumer of pictures, is whether there is intention behind the details. If there is, those details somehow concern me. If there is not, I will do my best to avoid them.

Let's share reality!

The internet gives unprecedented opportunities to share reality. For bad, but also for good. During the last two decades, there have been many complaints that people see too much of each other's lives: Plates of food, children playing, those new shoes. Things that were private before are now shared on social media. That flow of photos doesn't increase the aggregate knowledge of the world much, because it is mostly repetition. Everyone already knows more or less how a contemporary plate of food or a pair of shoes look.

But also, I can see what an entirely normal street looks like in Mexico, without going there. I can see works of art from all of history. I can see the interior of an ordinary Japanese home. That is an amazing opportunity. That is, if someone shows me. But instead of exhibiting different corners of reality, more and more people are gluing wallpaper all over the internet because wallpaper has become so cheap.

This should be a golden age of depicting reality. These days almost everyone is carrying a camera with them at all times. Most probably, more images of the real world are created than ever before.

The problem is distributing and organizing those of the photos that people are willing to share. Wikimedia Commons has been one of few examples of image distribution that is actually working. Anyone can upload images to Wikimedia, tag them appropriately and others are then free to use them and propagate them. Visions of reality accessible to all. For that reason I am alarmed that AI images are turning up among Wikimedia’s images of century-old paintings.

One simple solution would be to create sanctuaries for images of reality. A blanket ban of people's own AI art on Wikimedia would be a first step (if there is not such a rule already).

Another step lies at tech giants. If they wanted, they could create services for image sharing. People could just label some of their photos free-to-share and add a description and then upload them to a common database.

Another important step would be to discuss copyright law. Image-creating AIs harvest data from copyrighted images and churn them together to unreality. That is legal. Just republishing copyrighted images of reality is not legal. As things are, the law punishes republication of reality, but not of reality churned-together into unreality.

Copyright laws are there for a reason. People don't want their photos used on the wrong occasion. For example, people who publish their party pictures on Facebook don't want those pictures transformed into genre images on binge drinking. Professional artists and photographers also have to live, and so on.

Reality is a mess. It is riddled with conflicts of interest. In many ways, transforming everything into fiction escapes those conflicts. And still, that is a really bad solution.

The introduction of LLMs dropped the marginal cost of producing bullshit to 0. The supply is therefore limitless. People will notice and adjust their subjective valuations of bullshit accordingly. My hypothesis is that this will lead to a retrospective revaluation of much of what we have taken to be progress over the last quarter century, and we will get the widespread acceptance of the astronaut meme: “It always was.”

About information content, can we put it like this: When looking at an old photograph, you get information about things those long-dead people used and found deserving to show, but none about the color scheme of the surroundings (cause it's black-and-white). When a child draws a picture of a man, you get all kinds of interesting information about the development of human abstract imagination, but not much about the anatomy of an actual man (it's drawn with just the head and two long legs). Looking at an advertisement photo with happy people having good time you get to know what the ad experts think people like, but not much about the actual people using their product. And looking at AI art, you can't get much good info about real world, but you do get some glimpses into how the AI's mind works. For example, if you ask for the 18c Netherlands style painting, what are the characteristics of that period paintings it will find necessary to replicate? Will it always draw a Santa Clause if you ask for a man and a deer? How much more compute does it need to stop messing up the numbers of legs? Does it get less and less dreamlike with more compute and training data?